US Copyright Office sides with photographer in Warhol infringement case

The case concerns a portrait of Prince, photographed by Lynn Goldsmith, which served as the reference work for Warhol’s Prince Series.

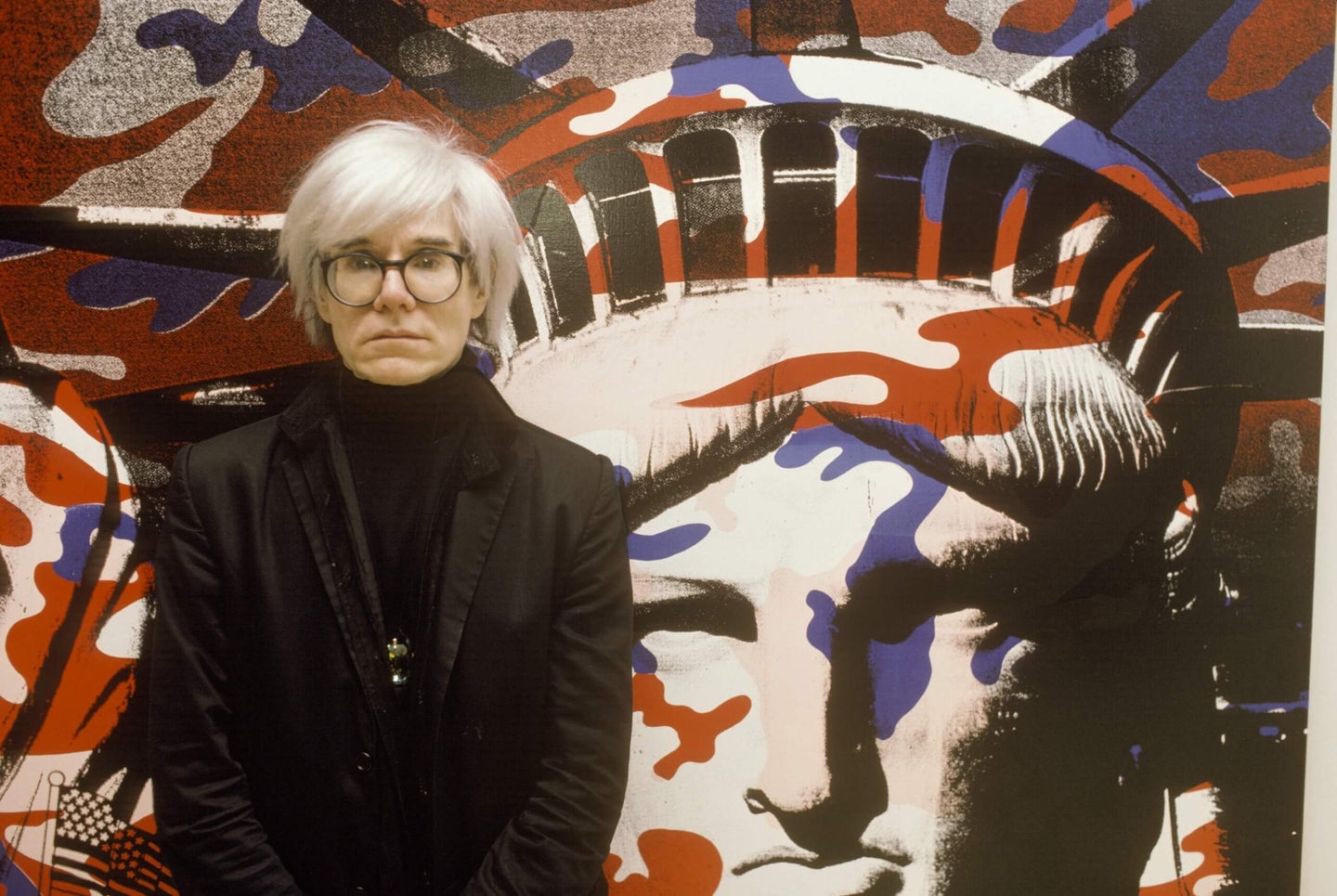

First Dua Lipa, then Snoop Dog, and now Andy Warhol. The unlikely group have something in common: All have had a copyright entanglement. From Snoop Dog’s controversial opinions on the topic to Lipa being sued twice, the laws surrounding image rights come back to bite. Such is the matter in this five-year running Andy Warhol copyright infringement case. Set to be heard by the Supreme Court later in the year, the case centers around Lynn Goldsmith, the photographer behind a famous image of Prince that was adapted into a piece of Warhol work. Appearing everywhere from the Smithsonian to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Goldsmith’s images have documented some of history’s most notable figures. A new an amicus brief from the United States Copyright Office is the latest chip to fall in Goldsmith’s favor.

Related: Keep your photos from getting stolen on the internet

How the Andy Warhol copyright infringement case developed

It started when the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) licensed artwork in 2016 to Vanity Fair for a commemoration of Prince following his death. In 1981, the magazine had licensed Goldman’s portrait of the artist for $400 with the intent of using it as a reference work. At the time, the photographer was not informed that Warhol would be using it as a base for 16 artworks now known as the Prince Series.

“It is a crime that so many ‘artists’ can get away with taking photographers’ images and painting on them or doing whatever to them without asking permission of the ‘artist’ who created the image in the first place,” Goldsmith wrote in a January 2015 Facebook post.

Her complaints to the foundation resulted in a preemptive lawsuit by AWF against Goldsmith, which it hoped would set the precedent on “fair use” policy should the photographer seek legal action. In 2019, a Manhattan district judge ruled in favor of AWF.

“The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” wrote United States District Judge John G. Koeltl. “The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince—in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

Related: Are these 16,000 photos of Picasso’s work ‘fair use’?

Turning of tides

Luckily for Goldsmith, 2021 brought a victory: The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the 2019 verdict, ruling in her favor. “Crucially, the Prince Series retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements,” wrote Judge Gerard E. Lynch. “We feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that ‘each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol.’’ Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.”

What’s happening to the Andy Warhol copyright infringement case today

Now, in 2022, an end for the five-year legal battle is in sight. Following the 2021 ruling, AWF requested to present the argument before the Supreme Court. Earlier this year, the Court put it on the Orders List, granting permission for writ of certiorari, meaning that the higher court would review the case.

While there has yet to be a hearing, several organizations have already submitted amicus briefs in favor of Goldsmith, including the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) and American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP). An amicus brief, officially amicus curiae, is a brief submitted by a party not directly involved in a legal proceeding but can petition to submit information that might influence the verdict.

“The fair use defense was never meant to give infringers a pass so long as they claim some new subjective ‘meaning or message’ in their derivative use regardless of how it is used, and neither this Court’s prior holdings nor common sense support that position,” write the NPPA, ASMP, and Getty Images in a joint brief. “Rather, any purported new meaning or message is only relevant in the context of a qualitatively different purpose or use than that of the original.”

However, the most notable amicus brief was written by the United States Copyright Office, which concluded its argument by recommending that the court of appeals judgment be affirmed.

“The allegedly infringing use here involves the commercial licensing of an image of Prince to accompany a magazine article about Prince,” the brief reads. “Goldsmith’s photographs have previously been used for the same purpose, and licensing of the sort at issue here usurps the market for the original photograph. And while petitioner argues that Warhol intended the Prince Series images as commentary about celebrity, petitioner has not argued that incorporation of the Goldsmith Photograph’s creative elements was essential to communicate any such message.”

While we won’t know the verdict for some time, it’s clear that the decision, whichever way it leans, could cause ripples throughout creative communities.