Photo Revolution explores the untidy history of photography as an artform

The exhibition is currently on view at the Worcester Art Museum.

Prior to the 1960s, it was unlikely that one would find the work of photographers inside the walls of museums. Photography, in many ways, was seen as a documentary tool and not as something that should be collected and preserved. But all of the sudden major museums around the country began adding the medium to their collection.

“I always wondered why that was the moment that this seemed to collectively happen,” explains Nancy Kathryn Burns, the Stoddard Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Worcester Art Museum and the curator behind the Museum’s current show Photography Revolution. “I have had this in the back of my mind for years, like a tumbleweed bouncing around.”

![Robert Heinecken, Untitled [Are You Rea]](https://www.popphoto.com/uploads/2019/12/16/TMUFCKHOYFFRXDTA3ELUASLGCI-752x1024.jpg?auto=webp&optimize=high&width=100)

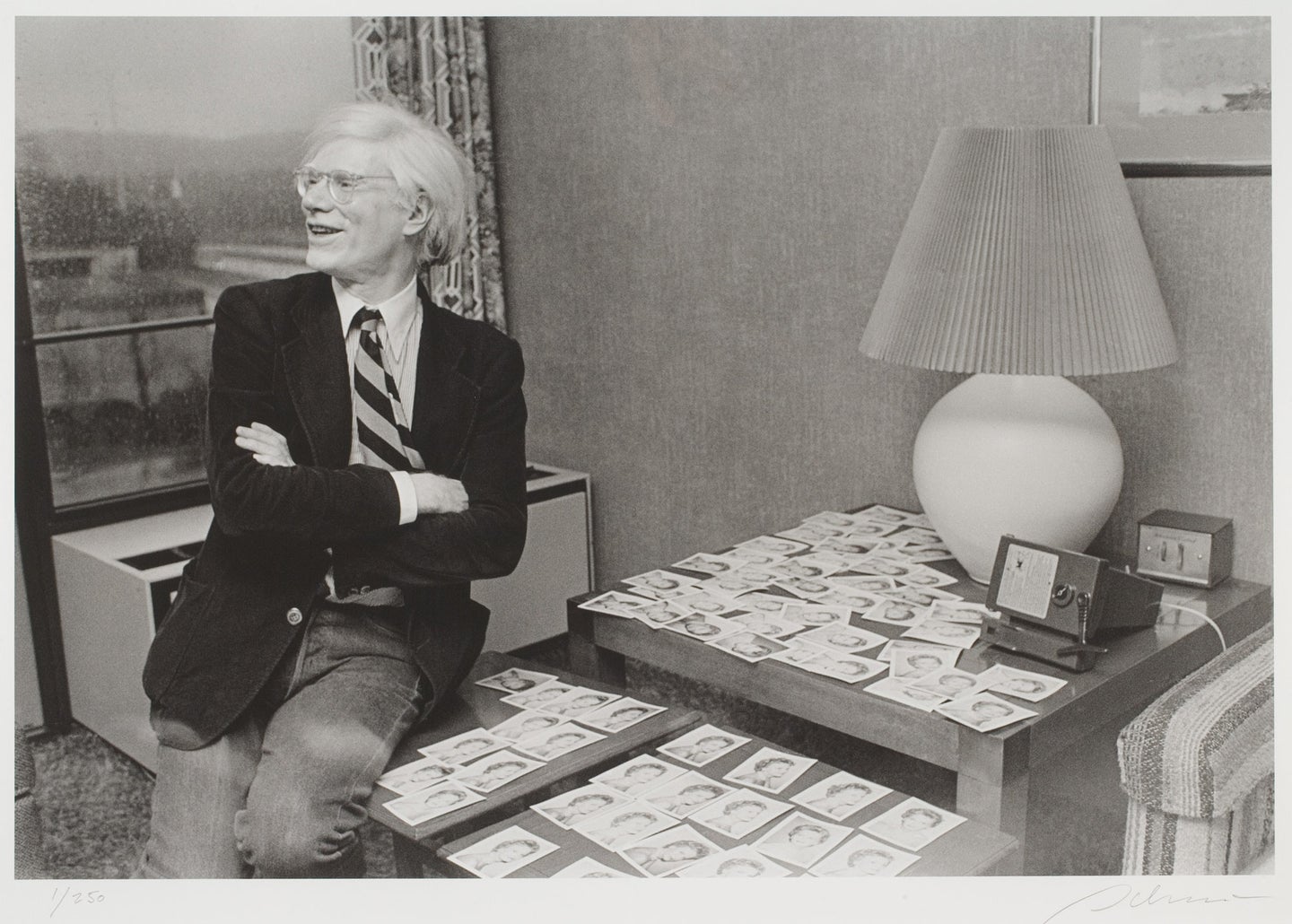

Photo Revolution: Andy Warhol to Cindy Sherman explores the symbiotic relationship between photography and fine art and the ways in which photography was finally able to establish itself as a serious medium in the museum world.

“Photography really undergirds a lot of the art work that we associate with artists who are working in other media,” says Burns. “If that is what is happening, maybe that is how photography inched its way into the museums on its own terms.”

Andy Warhol, The Art Worker’s Coalition, Martha Rosler, Richard Hamilton and others are all deeply indebted to photography or videography. Many of these artists were also looking at what it meant to be an American. According to Burns, artists like Robert Frank and William Eggleston have a lot more in common with fine artists of the period than previously acknowledged.

The period also coincides with the rise of television, and the explosion of television news—which had a direct impact on the art of the time.

“We talk about Vietnam as the living room war, news was coming through your television and traditional news sources. People were really being inundated in a way that you hadn’t seen before,” Burns says. “The immediacy shifted considerably.”

Artists like Richard Hamilton used a camera to photograph the news of the Kent State shooting from his television—making literal screen shots—and then turning them into screen prints. According to Burns the photo and video documentation of these events shifted the public’s relationship with photography significantly.

During this same era consumer cameras like the Kodak Instamatic made it cheap and easy for everyday people to document the world around them. The exhibition includes a sizable collection of vernacular photography from the era.

“Everyday people were taking very similar photographs and choosing very similar subject matter as the people that we think of as great photographers,” says Burns.

Although the title of the show implies that visitors might move through a timeline, Burns says that it was important for her to avoid a perfectly linear narrative.

“It is too untidy of a moment to do that. It also wasn’t how the movement worked. I wanted to retain that,” she explains. “So many ideas were coexisting at the same time, I didn’t want it to be a perfect package.”

Photo Revolution: Andy Warhol to Cindy Sherman is on view at the Worcester Art Museum through February 16.