Portraits from the Edge

Lynn Blodgett's empathetic pictures of disenfranchised Americans remind us that we're all human.

Photographer Lynn Blodgett has a demanding day job: He’s president and chief executive officer of Affiliated Computer Services, Inc., a Dallas-based Fortune 500 company specializing in information-technology outsourcing that employs some 58,000 people worldwide. But he has been avidly pursuing his avocation of photography for several years, a passion that eventually led Blodgett to study the craft with renowned celebrity portraitist Andrew Eccles.

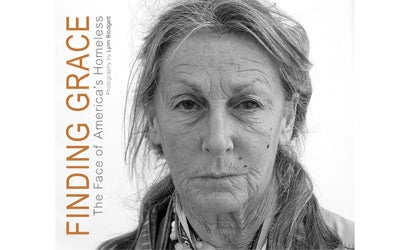

In his most recent project, with Eccles’s encouragement, Blodgett has focused his lens on people with whom he might appear to have little in common — homeless citizens in various cities throughout the nation. His series of black-and-white portraits resulted in a remarkable monograph, Finding Grace: The Face of America’s Homeless (Palace Press, $55), which American Photo included in its January/February portfolio of the Best Photo Books of the Year. (Proceeds from Blodgett’s volume will go to a charity called the Finding Grace Homeless Initiative.)

“I hope we can see beyond the myths that all homeless people are lazy, addicted, or crazy,” Blodgett says. “These are real people, and we can learn from them.” Many of Blodgett’s photographs were made in cities where he was conducting business; he often sought out people to photograph after a day of corporate meetings. When American Photo recently caught up with Blodgett, he had spent the previous days dealing with fallout from a big shakeup on the board of directors of his corporation — and also touring to promote his new book and campaign on behalf of the Finding Grace charity during Homeless Awareness Week. Here he talks about the genesis and evolution of his photographic work.

American Photo: It seems you have had quite a full schedule in recent days…

Lynn Blodgett: It was busy, and fun, and very exciting. There were lots of people interested and involved in the homeless cause, and quite a bit of money raised, so it was thrilling. We had photo exhibits in several cities, and people were very complimentary of the pictures, which as a photographer was fun to hear. And I hope it actually is helping people to see that there are lots of different kinds of homeless people. It’s not just one type of person, and maybe that will help break some stereotypes.

AP: Did you ever expect to be involved to this extent in this sort of cause?

LB: No, I didn’t, but it is very rewarding. You know, in Los Angeles, to stand up there on a big stage with thousands of people out there getting ready to walk [to raise charity funds] — I certainly had not anticipated that when I started making these photos.

AP: You’ve said that this project came about during your studies with Andrew Eccles. Could you explain?

LB: I had taken a class at the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops, and they sent me a catalog and I noticed a wonderful portrait of Ashley Judd, and it was on a course for editorial portraiture and Andrew Eccles had taken the picture. It caught my eye and I read the thing, and you had to submit your portfolio and it was for advanced photographers, so I figured I wouldn’t even get into the class. But I was lucky enough to get in and I met Andrew. He’s a terrific teacher. Everybody in the class was a professional photographer except me, and Andrew asked, “What do you want to get out of this?” I said, “I would just hope that someday somebody like you would think that some of my pictures are good [laughs]. Not great, but at least good.”

AP: Did you hope to get published?

LB: No, I just wanted to take some pictures that somebody who was good would look at and say, “Yeah, that’s a good picture.” And I had this idea later on to work on a book about poetry with photos to go along with the poems. Classic poems, like Robert Frost or whatever. So I began to work on that and I put together about a hundred layouts that I thought were pretty good, and I took them back to a man in New York who is very much an expert. And he thumbed through them and said, “Yeah, they’re good — for an amateur.” And it just killed me. I thought, “What a brutal world.” And I was upset for a few days and then I thought, “I just need to get better.” And I had so enjoyed Andrew — he could be very direct but he wasn’t mean about it. He could help you without you feeling dismantled. So I called his agent and said, “I’d like to hire Andrew, not to take pictures but to teach me how to take pictures.” And after several weeks Andrew agreed to do it, and roughly once a month I would go back to his studio in New York with my photographs and he would critique them: “This one’s no good, this one’s no good,” and then, “that’s pretty good.” Nothing ever got into the “very good” pile! And then he would teach me. He’d say, “Here’s what you did wrong, you got lazy on this shot,” or “the light was wrong.” And over time, a few pictures got over on the “really good” pile.

One of the poems I liked was about a homeless person, so I went to a shelter and photographed some people. And one of the first people I photographed said, “I’m a poet.” And he recited his poem about the Iraq War that was just stunning. And I thought, “There’s more to these people than meets the eye.” That’s what really got me going. And then Andrew, as the portraits got better, he said, “I think you should forget the poetry book — but these are strong enough that if you keep working at it, these might affect people and they might make a wonderful book.” So Andrew gave me the courage to approach a publisher.

AP: When you were making these photographs, did you talk with the subjects, get to know them?

LB: Well, early on I went to a shelter and said I’m going to do a book, and the proceeds will go to the homeless and won’t it be wonderful, and the people were like, “What are you, nuts? You can’t take my picture.” And so I said, “I’ll give you ten dollars.” And then it was the kind of thing where people lined up. And I tried not to go in and select certain people, which would have meant I’d miss many of the best photographs. Because a lot of what came through in the photos was from people who looked, on the surface, somewhat ordinary. And yet when their moment came to be photographed, there was something about them, in their eyes, or in their soul, that came through that I wouldn’t have seen if I’d have just tried to pick who I thought was interesting.

So they would just line up. I typically spent just a few minutes with each one. We’d put up a piece of white seamless paper in shallow shade. No lights — just available light. I tried to shoot at least at f/8 at about 1/125th shutter speed, usually at ISO 100. With many people, I didn’t want them to stop or to say, “Stand still” — I didn’t want them to feel rigid — so it was a bit of a trick to keep the shutter speed up and the aperture such that we had enough depth of field so they came out okay.

AP: What kind of camera did you use?

LB: I started with a Canon 1-DS Mark II, which is a 16-megapixel D-SLR, and I shot with that for a long time and I loved the results. But then Hasselblad came out with their 39-megapixel medium-format camera, and I started to shoot with that. They have completely different qualities, and some of the shots that are more film-like, I guess you could say, are done with the Hasselblad, and some of the ones that tended to be a little grittier were shot with the Canon.

AP: In the book, some pictures have biographical information and some just names. Was that a function of how much time you spent with them?

LB: Sometimes I didn’t get much out of people. I’d say, “Do you have kids?” “Yes.” “How many?” “Two.” You know, just trying to get a little rapport. So in some cases we didn’t have a story. I did have enough photographs so that if we’d wanted to run only ones with stories, we could have. But we felt that it was better to leave some of it open. Because people who look at the book will say, “That person reminds me of my uncle,” or, “that person reminds me of me, when I went through a tough period.” It allows people to do a little more relating of the circumstances rather than trying to fill in all the blanks.

AP: You mentioned that you found people in shelters — did you also find people on the street?

LB: Oh, I always shot people on the street. There were only a couple of situations where I actually photographed on shelter property. The shelters were a little dicey about letting me take pictures on their premises. So I typically would find people who were hanging around shelter areas, and then I’d go ask a business if I could use one of their walls outside as a backdrop, and tape my paper on it, and then I’d shoot. It was on the street.

AP: Could you tell, by looking, who was actually homeless?

LB: Yeah. I mean, that’s a question I’ve been asked and, first of all, how do you define homeless? Does it mean you’ve been out on the street a week? Or two years? You know what I mean. There’s a definition there, but I went to places where there were clearly homeless shelters right there, within immediate proximity. You’re making some judgments, obviously, but people who appeared to be definitely homeless, I would ask them to help me find people who would participate. If there was someone who wasn’t actually homeless, it was the absolutely very minor exception. I did meet people who had been abused and were running away — women who had escaped. And I sometimes didn’t know how long they had been on the run.

AP: Was there something with this group of people, any qualities that you noticed over and over?

LB: They were very respectful. They were interested, they wanted to participate — they wanted the money, but they also felt like it was chance for them to be recognized. Also, they policed each other. If somebody did get rowdy, like if somebody started to use a lot of profanity or whatever, I’d say “Listen, if you keep this up I’m going to leave.” And the rest of them would say, “Shut up!” or whatever, and get them in line. I could use that as a tool to get people in order. But they respected what I was doing and they appreciated it. After every shoot, I would have many of them say to me, “God bless you for what you are doing, and God bless you for helping us.” Or, “I needed some bus money to get back to wherever, and with this ten dollars I can do that.” They were appreciative and I think genuinely grateful that someone was trying to give them a voice. And not in a militant way — it wasn’t like going out and following a CNN truck to get on the news — it was that they could actually have some dignity and share their experiences.