6 photography exhibitions worth viewing right now (Nov & Dec 2021)

A list of intriguing fine-art shows taking place at museums and galleries throughout the U.S. through the end of 2021.

At the height of the pandemic, about a year ago, the interiors of many fine-art spaces—from the largest museums to the smallest fine-art galleries—must have looked like scenes from an apocalyptic “Twilight Zone” episode: No visitors were able to go in and gaze at or closely study any works of arts. I imagine that at some of the largest museums, there must have been nothing but empty room after empty room after empty room. However, today, many museums and galleries have reopened, which is a reason to celebrate, to a degree. But I can’t forget that only several months ago many of these fine-art institutions were shut off from us. It’s a notion that made me look at some of the photos that are currently showing throughout the U.S., in a new light.

For instance, before the pandemic, I wouldn’t have considered why Ilse Bing created her wonderfully inventive “Self-Portrait with Leica” from 1931, which is currently in the show “The New Woman Behind the Camera” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. As a photographer who has always experimented with self-portraiture myself, I thought her motivation for using herself in the mirrored “double image” was purely aesthetic, which it is, of course. But after the pandemic, another thought occurred to me: Perhaps she wasn’t able to find a model or perhaps she feared being around others, and was making the best use of her isolation.

I’ve enjoyed the brilliant work of Abelardo Morell for decades: In many of his photographs, he’s captured surreal images of rooms he’s turned into makeshift camera obscuras, and photographed those interiors. The result is an upside-down exterior world projected over a dark, uninhabited interior room. And it’s not hard to grasp why I might look at an image like Camera Obscura: View of Atlanta Looking South Down Peachtree Street in Hotel Room, from 2013, in a new light. It is currently on view in the group exhibition “Picturing The South: 25 Years” at the High Museum in Atlanta. In the back of my mind, I again think that perhaps the photographer is somehow looking to bring the outside world into his isolated interior. But that world is upside-down, which for me, now, seems like the perfect visual metaphor for how many of us felt during the pandemic.

There are lots of other impressive photography shows taking place throughout the country. Check out the links to the following shows, some of which will still be open through 2022:

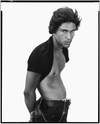

“Richard Avedon: Ten Exhibition Prints from In the American West”

This fascinating show at the Gagosian gallery presents ten large-scale Richard Avedon photographs—each of which measures almost seven feet in height. But it’s not just the scale of the images that make them monumental. It’s also the subject matter and his treatment in photographing them. Of course, all of the images still include Avedon’s classic seamless white background.

To produce this series, “In the American West,” Avedon took five years traveling through various western states. During that time, he photographed more than a thousand people, none of them celebrities or well-known. He selected 125 for the series, but chose just 10 photos, on view at the Gagosian gallery, to print at this monumental scale. What’s intriguing to note is that he cleverly uses portraiture, instead of the landscape, to define the theme of the series—the American West. In other words, he defines the region through portraiture…not landscape…by capturing remarkable images of its inhabitants. Many regard it as a key moment in both Avedon’s portraiture as well as the genre of photographic portraiture in America.

In terms of technique, Avedon used an 8 x 10-Deardorff field camera, which was positioned close to his subjects. Avedon also used natural light and the seamless white backdrop to emphasize his subject’s features, poses, and expressions.

Where: Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, California

When: Nov. 4, 2021– Dec. 18, 2021

For more info on the exhibition, go to the gallery’s website at Gagosian.com.

“The New Woman Behind the Camera” group exhibition

This powerful group photography exhibition focuses on the work of women photographers from the 1920s through the 1950s. According to the curators of the show, although women had actively participated in the development of photography soon after its inception in the 19th century, it wasn’t until the 1920s, after World War I, that there was a dramatic increase in women working in the field of photography. As the show reveals, many of these women photographers would bring innovation to a range of photographic genres: from avant-garde experimentation and commercial studio practice to social documentary, photojournalism, ethnography, and the recording of sports, dance, and fashion.

According to Mia Fineman, a curator in the department of photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the venue that first showed this exhibition, the show also reveals how photography provided many of these women a new sense of freedom. “For women during this period, the camera was really a means of independence and self-determination. It allowed them to create images from their own perspective and it also allowed them to create a source of income to support themselves financially.”

The list of the photographers featured in this ground-breaking exhibition, which looks at this period in a global context, includes Berenice Abbott, Ilse Bing, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Florestine Perrault Collins, Imogen Cunningham, Madame d’Ora, Florence Henri, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Consuelo Kanaga, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Dora Maar, Tina Modotti, Niu Weiyu, Tsuneko Sasamoto, Gerda Taro, and Homai Vyarawalla.

Where: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

When: Oct. 31, 2021 – Jan. 30, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at NGA.gov.

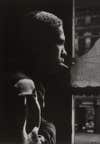

“Gordon Parks: A Choice of Weapons”

Gordon Parks (1912-2006) was born into a poor Kansas family in 1912, where he was the youngest of 15 children. But he would go on to become a towering figure in the world of photography during the twentieth century, working as a staff photographer for Life magazine for more than 20 years, from 1948 to 1970. But he would also become a pioneer in the world of filmmaking, becoming the first African American to write and direct a major studio feature, “The Learning Tree,” based on his semi-autobiographical novel.

The works in this exhibition—on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York City—are intriguing, in part, because they explore the roots of Parks’ future as a filmmaker, revealing the artist’s cinematic approach via his still photography and photo essays. The show includes some of the Parks’ most celebrated works, including photographs Parks made while embedded with the New York gang leader “Red” Jackson in 1948 as well as images of the Fontenelles, a Harlem family that struggled to feed their eight children in 1967.

It’s an exhibition that aims to draw connections from how Parks documented American life and culture, which focused on social justice, race relations, the civil rights movement, and the African American experience, and how this would emerge during the work he did as a filmmaker.

Where: Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

When: Oct. 8, 2021- Dec. 23, 2021

For more info on the exhibition, go to the gallery’s website at HowardGreenberg.com.

“Sarah Moon: At the Still Point “

The work in this show, which has a surreal, dream-like, otherworldly quality, was put together by the artist herself for Fotografiska and showcases a selection of her photographs, films and books produced over the last 30 years.

Sarah Moon (b. 1941), who was born in England and started out as a fashion model in the 1960s, eventually began working as a fashion photographer and filmmaker in late 1960. Some of her achievements include several books, including “Improbable Memories” (1980), “Little Red Riding Hood” (1986), “Vrais Semblants” (1991), “Inventario” 1985-1997 (1997), and “Photopoche” (1998). Her photos have also appeared in a variety of magazines, including Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Marie-Claire, Graphis and Life, to name a few. She has made more than 150 television commercials and has produced a documentary film on the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1995).

Moon won the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for Applied Photography in 1985 and the Grand Prix National de la Photographie in 1995.

Where: Fotografiska New York in New York

When: Oct. 15, 2021 – Feb. 6, 2022

For more info on the exhibition and how to get tickets, go to the museum’s website at Fotografiska.com/nyc.

“Picturing The South: 25 Years”

It may seem that fine-art museums are more interested in photographers and artists who have been dead for centuries than with those who are currently living, breathing, and working. But that’s not always true. Here’s one case in point: Since 1996, the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta, has commissioned photographers, both nationally and internationally, to explore the American South—both its rich social landscape as well as its geographic landscape—for its Picturing the South initiative. The initiative has allowed the museum to work with 16 photographers, and in doing so, has built a collection of more than 300 photographs.

This exhibition at the High Museum of art marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of Picturing the South initiative, bringing together all the commissions for the first time.

Works include the first photographs in Sally Mann’s “Motherland” series; Dawoud Bey’s larger-than-life portraits of Atlanta high school students; Richard Misrach’s Cancer Alley industrial landscapes; along with previous commissions by Alex Webb, Emmet Gowin, Alec Soth, Martin Parr, Kael Alford, Shane Lavalette, Abelardo Morell, Debbie Fleming Caffery, Alex Harris, and Mark Steinmetz. The show also presents new commissions by An-My Lê, Sheila Pree Bright, and Jim Goldberg.

Where: High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia

When: Nov. 5, 2021- Feb. 6, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at High.org.

“Jeff Wall”

This impressive solo exhibition of Canadian-born fine-art photographer Jeff Wall is his first in the Washington D.C. area since 1997. It’s also the largest exhibition on Wall’s work in the U.S. since a 2007 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

Who is Jeff Wall? During the 1970s, Wall was one of the photographers who was significant in contributing to the establishment of photography as a legitimate fine-art genre and fundamental independent contemporary art form. He was also one of the more interesting artists one might call “post-modern,” since he has created many works of art that are often about older works of art. But what made his work interesting is that at first glance, the narrative of these photographs is often about seemingly everyday life or ordinary moments. Since the 1980s, Wall has created panoramic vistas of suburbia, prefiguring his ongoing focus on landscapes at the margins, between nature and industrial towns.

However, the structure of the compositions is often based on art historical references to create new contemporary fine-art photographs, which he first displayed as transparencies in lightboxes blown up large, to human scale, which combined the scale of painting with the luminosity of the cinema screen. More recently, though, he has expanded to also presenting his work as large-scale inkjet color prints.

Take, for example, Wall’s photograph “Destroyed Room” (1978). It’s derived from Eugène Delacroix’s “Death of Sardanapalus” (1827) in its diagonal composition and red color palette. But the work is also about artifice: Through the door on the left side of the image, you can see that this is just a set, not a real space, held up by supporting beams.

Glenstone will also publish an illustrated catalog featuring an introduction by Emily Wei Rales, an original text by art critic and historian Barry Schwabsky, and color plates of the works in Glenstone’s collection.

Where: Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland

When: Oct. 21, 2021- March, 2022

For more info on the exhibition, go to the museum’s website at Glenstone.org.