Books of the Year: Alex Webb’s “The Suffering of Light”

Even if you’re familiar with Alex Webb’s eight other mass market books, a flip through his comprehensive monograph, The Suffering...

Even if you’re familiar with Alex Webb’s eight other mass market books, a flip through his comprehensive monograph, The Suffering of Light (Aperture), may leave you with a slightly different outlook on his work. The book (one of our books of the year) contains many of the Magnum shooter’s most iconic photographs, as well as many images that haven’t’ been published before. Over the course of his three-decade career, Webb has cultivated an extremely distinct style and aesthetic that he has applied to a wide variety of locations around the world. He considers it an obsession.

If you are in New York, do check out Webb’s accompanying solo exhibition at Aperture Gallery through January 19.

**Stan: This retrospective book was in the works for some time. How did it finally become a reality? **

Alex: The first glimmerings of this book started, I don’t know, 10 or 12 years ago when I was in discussion with a museum in California about the possibility of a mid-career survey show. We assumed there would be a book connected with it. That didn’t happen. Finally it ended up with Aperture. It was a long circuitous thing and at times I was a little impatient with it, but it’s a better book now because I’ve done more work since 12 years ago.

Did you find it particularly challenging to put together a retrospective like this instead of a more traditional book tied to one specific project or location?

I think the challenge was to try and make it into a book that I found exciting to make. Rather than just saying, “Here are Alex Webb’s best pictures from a certain number of years,” I had to make it into something that had a book feel to it. Sometimes I have reservations about survey books, but I think this is a way to more directly get at the central passion or obsession I’ve had as a photographer which was working a certain way with color.

When did that obsession first come about?

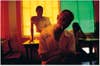

Before 1978 I had worked some in color, but I just didn’t take it seriously. I thought, “OK, this is just something that I’ll do to help me make a living. Black and white, that’s where my heart lies. ” But, I made a trip in 1978 to the US/Mexico border and I did take a little bit of color film with me. I did some work in some of the neon lit prostitution areas on the border. Just a little bit. But, I could see that there was something I was doing in color that was sort of different. There is this sense of searing light and vibrant color. This was part of the visual and emotional experience that I had in these places.

Was it a difficult process to go through your large photo catalog and come out with a cohesive set of photographs?

Sure, it’s complicated, going through one’s work and cutting it down. Certain pictures I knew definitely would always be in it. There are others from various odd projects that popped up, which hadn’t been published before and that made it very exciting. It’s not just selections from the eight other books. If you don’t include Dislocations, which was a limited edition book different from the mass-market books, 35% of the pictures haven’t appeared in my books.

Gouyave, Grenada, 1979

Did this new context change the way you saw those photos?

Sometimes there are pictures that get lost as individual images in the context of a certain book. Some don’t, clearly. I mean, the arrest picture from the border, or the cover of the red bar from Half-Made Worlds. They don’t get lost. But there are others that I think people have forgotten about. Bringing them into this book, presenting them in this way as part of a particular vision, makes people look at them in a different way.

The book is presented chronologically. While putting it together, were you able to see any previously unseen patterns or landmarks in your evolution as a photographer?

I think the thing about my work—and this isn’t true of all photographers—is that it does kind of follow a continuum. There are differences. There are emotional differences between the work from Haiti and the work from Florida or the Amazon. But, it’s still clearly the same photographer working the same way, just striking different emotional and visual notes. I think there are other photographers who have made very distinct decisions. They say, “For this project, I think I’ll use this format.” There’s a much greater distinction between periods of their life as a photographer. For me, there is this ongoing passion or obsession that is underlaying these 30 years that I keep trying to explore in different ways.

How about on a more granular scale?

It was interesting to see the way projects appear and disappear. Some have these long arcs of completion. It’s interesting to look at how I think the experience of working one place may have affected how I approached another. For instance, I noticed it in a couple of my pictures from Mexico in ’87. I was in the midst of my Haiti project and some of those pictures are much darker emotionally than my earlier Mexico work. I sort of wonder if it was from spending all that time in Haiti, which was certainly a much darker and more intense place. This new book reflects the complicated process of creation where projects overlap and speak to each other in some way.

Much of your work takes place in border areas. What is it that draws you to those places?

I’m not sure what it is that intrigues me so much about borders, but I know that I am drawn to places where cultures come together. They mix in surprising ways, sometimes easily, sometimes roughly. I love the notion that, on the street in a Mexican border town, you can think that you’re in some weird extension of the United States. Then you can cross the street and all of a sudden you can think you’re deep in the heart of Mexico. It’s the same way in Istanbul. You can be in a hip European bar and think you’re in Barcelona. Then you’ll walk into a place around the corner and think “Oh, now I’m in Uzbekistan.” I’m fascinated by being able to pass through places that are filled with complicated contradictions. It has been a significant theme in my work throughout. Maybe it’s a reaction to the perceived homogeneity in my New England background. Maybe if I ultimately understood it, I wouldn’t be able to photograph it anymore [laughs].

What’s your process like for actually deciding which places you’d like to go and photograph?

It’s very organic. I know there are some photographers who say, “OK, I’m going to start on a project and I’m going to do this, this, this, and this.” For me, I read about someplace and it sounds interesting and I make a trip there. I don’t know what I’m going to find and I try to approach it with as open a mind as possible. Of course, I bring all my personal prejudices and so forth, so I don’t go with a totally blank mind, but I don’t keep an agenda. I’m largely driven by curiosity. Where the project goes after that—if it becomes a project, because sometimes they don’t—I don’t really know. I set off on a journey and I don’t know where it’s going to end. It’s like when novelists create some characters and all of a sudden the characters take them on a story that they weren’t expecting.

Bombardopolis, Haiti, 1986

You actually have an academic background in both literature and history. How does that play into your work as a photographer?

I was really more involved with literature than history. When I was a young photographer, my initial interest in a place was often sparked by reading a piece of fiction set there. It’s not the facts of the place, it’s the feel. The atmosphere. My first trip to Haiti was at least partly inspired by reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, which is a novel set in Haiti. It’s not so much that way anymore, but there’s a deep relationship with literature in my work, it’s just way at the back.

Besides the fiction, what kind of other prep work do you do before leaving for a new destination?

I read a few guide books to know enough about a place to get going. But, I don’t read too deeply until I’ve also had some visual time on the ground with the camera. I don’t want to approach a place with too many preconceptions. I find that if I read too much, I have too many ideas in my mind about what I should or shouldn’t be seeing. I will try and make symbolic relationships between things which may or may not actually be part of my experience. I really believe that whatever ideas exist in my work come out of the experience of wandering and walking. My wife, who is also a photographer, likes to say that her pictures are smarter than she is—that they lead her. I feel the same way.

Have you found it increasingly difficult to simply wander around places with a camera due to various types of civil unrest or even just because of the sheer number of photographers currently trying to adopt the same approach?

When I was working in Haiti extensively, you could wander anywhere. People might be following you around and kids might be hanging off you, but you didn’t feel physically threatened. Maybe during times of political violence you felt threatened, but not others. I haven’t worked in a place that’s as intensely volatile as Haiti for many years. At 59, I may not be as ready to do that as I once was. You know, I can’t run as fast [laughs]. But it still amazes me when I’m out there in the world with a camera how often one can enter a situation and people will feel comfortable with you being there. You can wander into situations and make photographs.

Have you felt the urge to return to Haiti to capture the post-earthquake atmosphere?

When the earthquake took place I was in the midst of something else and I did feel kind of bad about it. Part of me also feels like, with that number of photographers down there, what am I going to do that’s different? I worked in Haiti during the U.S. invasion in ’94 and there were hundreds and hundreds of photographers. I feel a little useless being in situations where there are 12 photographers trying to take the same picture. I sort of wonder, what’s the point? Obviously it is critical that those things be photographed, but I tend to shy away from situations where large numbers of photographers go. I go to places where there is cultural conflict or even occasionally outright conflagration, but they tend to be the places that aren’t’ where the world of photojournalism is descending continuously.

I have photographed in plenty of news situations and I think I have done a good job. There are marvelous new photographers out there who are better at capturing the peak moment. I do something else that tends to be more ambiguous and more questioning. I’m not looking for photographs that give answers. I’m looking for photographs that ask questions.

Palm Beach Count, Florida, 1988

You’ve recently been doing some work here in the United States. Is that new work similar to the project you did in Florida, or will it be something wholly different?

I think the Florida book is consistently filled with humor. Perhaps it’s dark humor, but it’s humor. I don’t feel that’s quite the same as the work I’ve started doing in the US. But, it’s difficult to say much about it right now. It’s generally true that I have a terrible time talking about work I’m currently doing [laughs]. In hindsight, I can look back and talk about it, but when I’m in the midst of it, I feel that on some level I photograph to understand what it is and why it is I’m photographing. It’s a process of understanding. And until I get into a project a certain amount and I’m able to look at the photographs and see how they talk to one another and leading me where they will lead me, I remain hesitant to say too much because I’m not sure I really know.