Welcome to the Golden Age of DIY Photo Books

In the late aughts, like many photographers, Phillip Buehler was working on a promising book and searching for a publisher....

In the late aughts, like many photographers, Phillip Buehler was working on a promising book and searching for a publisher. Since 2001, he’d tenaciously pursued a photo-driven project about Woody Guthrie’s sunset years with help from the folk singer’s daughter Nora and the Woody Guthrie Archives. “We approached a lot of the big art publishers, and we had two very interested,” Buehler recalls. “And then the market tanked.”

Buehler’s proposal was in limbo. “Once we were at a meeting where a publisher sort of let on, ‘This is a do-good book,’” he recalls. “Which immediately puts it in the category of, ‘There’s not money to be made in it.’ And it almost dooms it.”

Yet Buehler knew he had a special project in the works—a view of a period of Guthrie’s life that has long been shrouded in mystery. It began as a photo shoot at New Jersey’s Greystone Park State Hospital, where Buehler was working on his ongoing series on modern ruins. He discovered that Guthrie had spent five years at Greystone in the 1950s and ’60s, when the singer was incapacitated by Huntington’s Disease. He learned that a young Bob Dylan visited Greystone to meet his idol. Further probing led to letters that Guthrie wrote from the hospital and recollections of his time there from kin including Nora, Guthrie’s son Arlo, his second wife, Marjorie, and friends such as singer Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and photographer John Cohen.

“It took a long time to follow all these trails,” Buehler says. “I’d been working on the book for a decade. And then it’s like, how do we birth this baby? How do we bring it out to the world?”

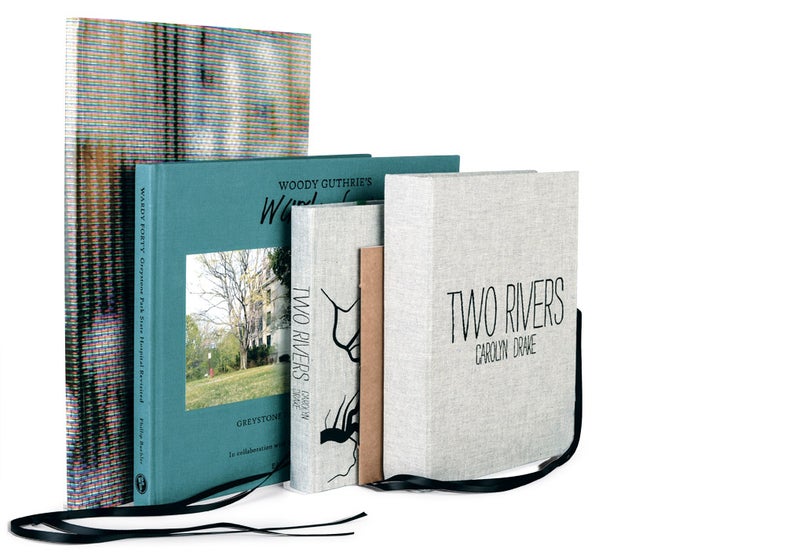

Buehler and the Guthrie Archives turned to an increasingly popular solution: self-publishing. The result is a poignant, handsome, 160-page volume, Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty: Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited (Woody Guthrie Publications, $75). The initial press run of 2,500 copies was robust for a monograph, independently published or not. At Nora Guthrie’s suggestion, designer and editor Stephen Brower collaborated on the book’s layouts. “With Adobe InDesign, we were able to design the book and send PDFs and work together without having to rely on a publisher’s designer,” Buehler says.

The printing was done by Meridian Publications in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. “More and more artists are bypassing the traditional way of publishing and distribution so they can control the production process,” says Daniel Frank, project director at Meridian. “The internet has enabled people to market their own books and sell them directly to the buyer. They can put more emphasis on production values.”

Buehler agrees. “Along came Kickstarter, which we used to raise money,” he says. “And we could promote the book on Facebook—we also put it on the Woody Guthrie page, Arlo’s page—so now you have, as an individual, a much larger audience than ever before.”

Buehler and the Guthrie Archives surpassed their fundraising goal of $42,000. “That helped with overhead,” Buehler says. “Setting up the press and the management of it cost around $30,000. And then every book after that is on a sliding scale, a calculation of time and paper and ink. We wanted to get the per-book rate down to a reasonable price.”

Buehler calls the self-pub trend “a transformation of an industry. These new things that came along made this possible, whereas ten years earlier when we started the book, they weren’t.”

Greater Recognition

Once the odd step-children of the publishing industry, independently produced books are getting new respect. Of hundreds of entries to the 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, 30 titles were selected for the contest’s shortlist—and nearly half of those were self-published. One of the honorees was Beautiful Pig (benschonberger.com, $70), by photographer Ben Schonberger of Alexandria, Virginia. “It’s been a huge boost—sort of like being shot out of a cannon,” he says of receiving the honor.

Schonberger’s project focused on Detroit police officer Marty Gaynor and his snapshot collection. “Among his thousands of photographs were images he had taken of criminals just moments before their arrest,” Schonberger says. “I’m interested in typologies of people, and this work allowed me to look at two very different ones—cops and criminals—at the same time.”With informal lessons from a friend, Schonberger learned how to use InDesign and laid out the book. While working in Detroit, he chose a nearby printer, Heath Press of Royal Oak, Michigan, and published a modest press run of 100 copies. “I signed and numbered all of them—100 felt like a good number for the first edition,” he says. “But now that the book has been well received, I’d like to make a second edition.”

Artistic Freedom

A small batch like Schonberger’s can be easier for a photographer to finance, but as Buehler discovered, producing a bigger edition often requires a substantial investment. Photojournalist Carolyn Drake, who has worked for clients including The_ New Yorker, Time_, and National Geographic, took the middle route. She says that for her most ambitious photo project—a five-year exploration of the vast Amu Darya and Syr Darya River regions in Central Asia that blends documentary and fine art—self-publishing a monograph turned out to be both the most practical and the most creative option.

“By the time I got around to contacting publishers, the book was already designed,” Drake says of her striking 2013 book, Two Rivers. Working with Dutch designer Sybren Kuiper of SYB in The Hague and funded by a Kickstarter campaign that surpassed its $15,000 goal by more than $9,000, Drake’s book was printed in an edition of 700 by Mart.Spruijt, an offset printing house in Amsterdam. The first edition sold out.

The physical design sets Drake’s book apart: On Japanese-bound pages, beautiful images spill from one spread to the next, emphasizing the interplay between elements over intact photographs. The volume’s unorthodox structure fit with Drake’s DIY model. “We didn’t have a lot of restrictions,” she says of self-publishing. “Pros: You make all the decisions, you have direct contact with readers and booksellers, and you know where your money goes. Cons: You make all the decisions, and you have to find ways to sell and promote it yourself.”

Creative Collaborations While a photo book’s success depends in part on the size of its audience, statistics aren’t everything. “It’s not just about the number of eyeballs anymore—we’re achieving more of that online than a print book is reaching,” says Michelle Dunn Marsh, cofounder of Minor Matters (minormattersbooks.com/), a publishing venture that combines an indie approach with a curatorial model for selecting artists. “The printed book allows something to have a life when you and I are gone. It’s an opportunity for a body of work to live on,” says Marsh, who’s worked as a publisher and design director for companies including Aperture and Chronicle Books. “If we’re going to kill a tree to make a book, what are the benchmarks for doing that?”

Minor Matters operates on a pre-sale principle: If a project achieves a 500-book quota of advance orders, it will hit the presses. “For each of the books on our website, we have worked with the artist to determine the size of the book, the cover, the design, and the conceptual details. When these are in place, we stop,” Marsh says. “And then we have a six-month period to obtain a minimum of 500 pre-sales. If and when that happens, we continue the production cycle of the book and it goes to print.” She adds that published books will be available from independent book outlets such as photo-eye.com.

“It’s probably a good idea for me to look for 500 friends right now,” jokes Anna Mia Davidson, a Seattle-based photographer who is working with Minor Matters on a book called Human Nature, stemming from her own experience in sustainable farming. “The images are taken on many different farms in the Pacific Northwest,” she says. “I’ve spent the past 16 years loving an organic farmer and embracing the life we share as a farm family, raising our children, and living off the grid in a yurt for several months each year. It was only human nature to turn the camera on my own world.”

Yet Davidson had kept this body of work mostly under wraps until Marsh encouraged her to publish it. “The part I love,” Marsh says, “is to work with the artist and say, ‘How do we share this work with a wider audience? How do we preserve it in book form?’ It all goes back to believing in what we’re putting on paper.”

As a veteran of the traditional book-publishing industry, Marsh has seen many a project flounder. “The publisher takes on the financial burden, and it goes out into the world, and if it sells 250 copies or it sells 2,000 copies, the photographer has got their 50 copies and they see the book in print,” she says. “In our model, there’s a possibility that the book is not even going to happen. That’s scary for all of us. But the truth is, we have more books today than we have audiences to buy them—and so that’s pushing people to try things in new and different ways.”