Revisiting Eugene Richards’ intimate portraits of poverty

The photographer’s 30-year-old body of work on life below the poverty line still resonates.

Still House Hollow, Tennessee, 1986

Great photography often comes from not being afraid to get close. Eugene Richards certainly isn’t afraid to get close to his subjects—both physically and emotionally. In many of his images you feel that Richards was so close to the people in his pictures that he could feel their breath. He is the kind of documentary photographer who believes in living alongside his subjects, getting to know them before ever raising his camera to his eye, and creating images that are intimate and honest. Below the Line: Living Poor in America, which was published 30 years ago by Consumers Union, demonstrates these qualities, which undeniably are some of his greatest strengths as a documentarian.

For the project Richards spent five months traveling across America and collecting stories from individuals who were living below the poverty line. He spent time in a shantytown in New York City’s Lower East Side, on bankrupt farms in the heartland, with migrant workers along the Texas/Mexico border, and inside deteriorating housing projects in Chicago’s inner city. In addition to photographing, he spent extensive time interviewing each of his subjects to create an oral history of their realities.

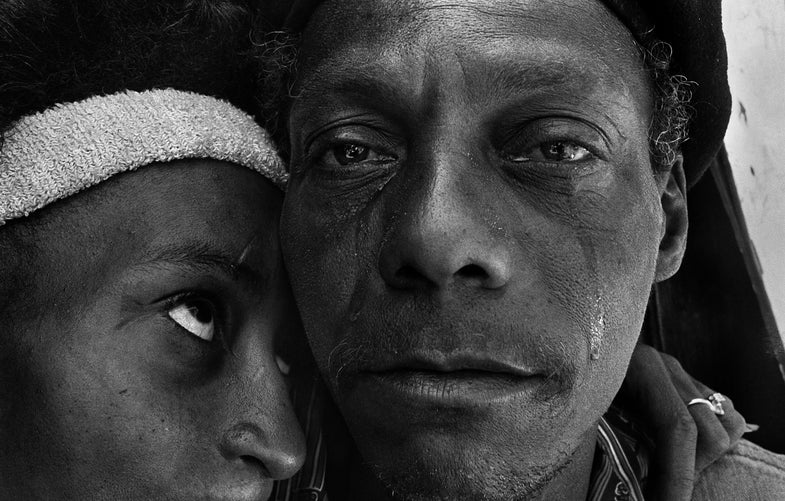

Porter Lee and Mr. Will, Hughes, Arkansas, 1986

“I think there are too many goddamn pictures. I’m very suspicious of pictures,” Richards recently told American Photo. “Context is really vital. If you do a text on somebody, it becomes much more difficult to put a cliché on them. And when you’re dealing with something like poverty, it’s a bounty of clichés.”

High on Crack, New York City, 1986

A selection of these photographs, and the stories that accompany them, are currently on view at the Bronx Documentary Center—a community based photography organization in the Melrose neighborhood, where the hardships that are depicted in Richards’ images are not abstract.

“The issues that are in there are absolutely the same issues that we talk about in the Bronx every day,” says Mike Kamber, founder of the B.D.C., “It’s people being forced out of their homes, living paycheck to paycheck, living with domestic violence, a lack of education, good housing, health care being for the wealthy. That’s what is in the show and that’s what we’re talking about here in the Bronx.”

Kamber says he remembers encountering Below the Line early in his career as a photographer and called the work influential on his own way of seeing the world.

Emily’s Second Child, Chicago, Illinois, 1986

“This work, it’s groundbreaking,” says Kamber. “In terms of the level of intimacy, the level of dignity and respect, he is exposing just as much as the most hardcore photojournalist, but he’s doing it in such an intimate, dignified way. This work is really something else.”

The personal nature of the images and the very real connection to poverty made for a compelling opening night at the B.D.C. Patrons seemed eager to discuss the issues at hand in the photographs as opposed to their technical excellence or beauty—something that didn’t necessarily happen when the pictures were first released 30 years ago.

“People are always nervous about poverty. At that time, no one paid any attention the the text—none,” Richards explains. “That’s what made the show in the Bronx very interesting. Everyone went in there and read the text. More often than not, people came up to me to discuss the text.”

Considering that 45 million people live in poverty in the U.S. and the gap between the very rich and the very poor continues to grow, Richards’ images continue to resonate, even 30 years after they were created. Although the photographer says he certainly sees the relevance of these stories all these years later, going through his archive and looking at this older work made him realize something else.

“I came to see that, in some ways, except for occasionally, I wasn’t photographing with the same kind of intensity,” he says. “I miss it.”

Back from Prison, Shantytown, New York City, 1986

Richards says in the next year he would like to put together a contemporary take on Below the Line that is focused specifically on the Bronx.

“You go into the Bronx and you can’t escape the problems with diet and diabetes, all of the manifestations of what that kind of ill health brings to you,” he says. “It was always there, but it wasn’t the primary thing you saw. Now you can’t escape it.”

Below the Line: Living Poor in America will be on view at the Bronx Documentary Center through Nov. 6.