Photography Fragmented at PhotoEspaña 2014

The debate rages on: Should a photograph represent real life or some aspect of its creator’s imagination? Is photography art?...

The debate rages on: Should a photograph represent real life or some aspect of its creator’s imagination? Is photography art? And what exactly defines a photograph, anyway?

Given the myriad creative tools of digital post-production—not to mention the image explosion in the age of cellphone selfies and social media—these questions still have tongues wagging, but they’ve been confounding image-makers for more than a century. For evidence, consider the multifaceted photo exhibitions at PHotoEspaña 2014, this year’s version of the annual photo festival headquartered in Madrid, Spain.

With more than 100 shows in venues throughout Madrid, PHE14 cuts a wide swath of genres and styles, “spanning a vast panoply of names and themes,” in the words of festival director Claude Bussac. This year the emphasis is on Spanish photography—but the visual content remains a global mix. And as Bussac notes during press week: “PHotoEspaña looks at the past, the present, and the likely future.”

The latter is front and center in “Photography 2.0,” a group show at Circulo De Bellas Artes through July 27. Reflecting the explosive effect of the Internet on modern imagery, the mixed-media work is organized in sections (Ubiquity Image, Hypervisibility, Intimacy/Extimicy) to render a bit of shape to an amorphous mass of artwork. It ranges from Jon Uriarte’s “CebriMe”—in which he poses with some celebs, composites photos with others, and lets you guess the difference—to Laia Abril’s “Thinspiration,” a haunting study of women suffering from anorexia nervosa. The collected work is as dizzying as cable TV and as engrossing as the Web. Which is the whole idea.

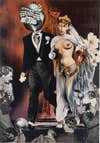

Yet scattershot images, and mixed-media experimentation, go way back—as evidenced by a companion show at Ciculo De Bellas Artes featuring photomontage wizard Josep Renau (1907–82). In the 1950s and ’60s, the Valencian Renau cut-and-pasted his way through a brilliant and scathing indictment of capitalism aimed squarely at the US of A: The collection “The American Way of Life” ranges from the pacifist fury of “Oh, this wonderful war…!” to the anti-sexist satire of “Chicago’s Miss Beefsteak”. Eschewing all stylistic bounds and mores, Renau fashioned Dadaism and Surrealism into piercing revolutionary weapons.

At the same time, across the pond, Lillian Bassman was quietly staging her own visual revolt, breaking down the conventions of the fashion-photo industry that employed her to shoot for such publications as Harper’s Bazaar. A dazzling exhibition of her large prints, “Brush Strokes,” runs at Lowe Fundación through July 27. Striving for the artistry she achieved in her painting, Bassman (1917–2012) photographed the female form as a abstraction of curves, made more painterly with brushes and chemicals in the darkroom. Angry about the lack of experimentation in fashion imagery, she destroyed many of her negatives in the 1970s—but an assistant secretly saved a trove of them, many of which comprise this show. Bassman enjoyed a renaissance in the 1990s, returning to the darkroom to reinterpret negatives and, later, even taking up Photoshop—she remained creative until her death at age 94.

Like Bassman, several Spanish photographers in PHE14 were avant-garde pioneers ahead of their time, praised and shunned and then rediscovered by the art world. In the early 1900s, Joan Vilatobà (1878–1954) strove to have photography accepted as a fine art; he embraced the pictorialism movement—with its romantic, symbolic sense of drama—and experimented with early hand-colored prints, as seen in a solo exhibition running through September 21 at Museo Nacional del Romanticismo. Three decades later, Antoni Arissa (1900–1980) went the other direction—giving up pictorialism in favor of an unadorned sense of realism, shown in a vast and brilliant survey of his work at Fundación Telefónica through September 14.

Halfway To Midland, Nancy Newberry

Two modern American photographers show how the imagined-vs.-real conversation continues. At Centro de Arte Alcobendas through July 5, Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s work is overviewed in “The Storyteller’s Language,” with his cinematic portraits veering between the public and the private, the documented world and the staged narrative. In the same venue through July 27, Nancy Newberry’s “Halfway to Midland” series evokes views of her native Texas with the sort of hyper-realism found in Gregory Crewdson’s work, without the elaborate sets—mise-en-scènes of Americana with a psychological undercurrent. Is it real? Is it art? Either way, it’s well worth a look.