Photographing the Cosby Accusers: Amanda Demme’s New York Cover Shoot

Amanda Demme on photographing the 35 diverse women that make up the unwelcome sisterhood

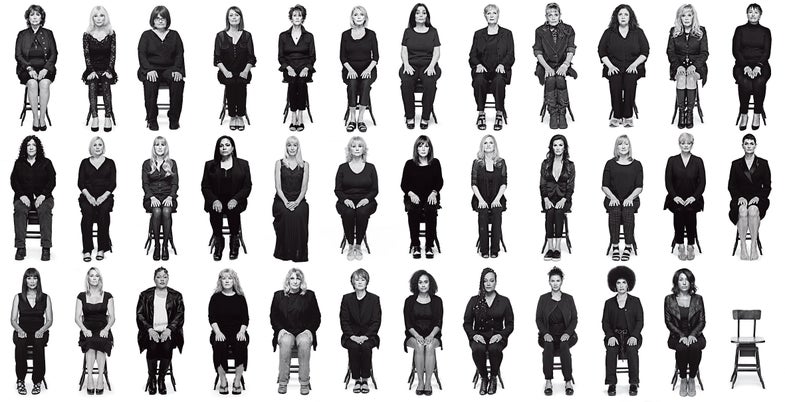

By now you’ve likely encountered the powerful black and white New York Magazine cover featuring 35 women (plus one empty chair) who have publicly accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault. The multimedia package, which was published on Sunday night, quickly spread across the internet and has been shared over 172k times. Photographer Amanda Demme says she jumped right in when New York Magazine approached her last March to make portraits of some of the women who had publicly accused the comedian of sexual assault.

As the project progressed the number of participants increased, shoots were arranged in studios in Los Angeles, New York and Las Vegas. The final two participants were photographed by Demme just a few days before the story was published online. In total Demme was able to photograph 35 of the 46 women who have publicly accused Cosby of assault.

Here, she talks about the logistics of her shoots and how she made these 35 diverse women feel at ease in front of her camera.

The portraits of Bill Cosby’s 35 accusers were shot in three different locations over a number of weeks—what did you do to keep the portraits from each of your shoots unified?

I set up every shoot exactly the same. I had two different backgrounds and within that I would have two or three setups. I stayed as consistent as possible down to measurements—I made sure I never changed my camera. My setup was faster in the beginning, and slower by the end because I had to really match it so that they all could work together.

How many women were you shooting at one time?

Sometimes I would have five, sometimes I would have eight, sometimes I would have one. I loved when I would get this giant group of ladies. Imagine a bunch of women who have been shutted up, and violated, and had experiences that they have never been able to talk about. It was so beautiful seeing women that had spoken via e-mail, or had never even met, be able to connect like that. And to feel beautiful, and to feel loved. They told their stories. They had sense of humor. They were incredibly poised, but they were fun.

How long were you spending on each portrait?

Two to three hours per woman.

The 35 women were a very diverse group who were brought together by a traumatic experience, how did you put them at ease in front of the camera?

I don’t like to be in front of the camera either. I hate it, and I understand. I think the most important thing was to give them a structure to follow that was super simple. I would cue them on how they were to feel when they looked at me straight on, and how they were to feel when they looked away. I would never let any of the women smile because this is not what this was. I didn’t want them to even notice that the camera is there. I always said:

Even if they’d never been in front of the camera before, they were able to key into that.

Then helping them put their hands in ways that felt natural, sometimes people are sitting there and they don’t know what to do with their hands. They don’t know what to do with themselves. We helped them through that. I cued them on things that they were actually feeling.

Each woman was shot in a number of scenarios in the studio, can you tell me about the thought process for the different setups?

I story board in a very un-traditional way. Every time before I shoot I create references and then when I go to set, I have a million ideas, and I set up at least three or four of them.

I did the sitting, which was my favorite, and then I did three others. I loved the concept of this massive group, but not in a clusters grouping like wedding photos. I wanted to find something that would marry to my painterly look, which was the individual color portraits, and I liked this clean, military, very clinical look. When I approached the black and white series, the way I lit it was that I wanted them to look like they were actually sitting on top of the background. I also wanted it to look very clean. How do you do that with that many people, and with that many heights, and with that many colors of hair, and that many body shapes? I feel like that’s what sitting down did.

Did you know that was going to be on the cover when you were shooting it?

I never knew they were going to use it as a cover. I presented it to them as a cover and to Jody Quon’s brilliance she pushed it through the channels. At first they wanted to make it color—most magazine’s don’t like black and white on their covers, per say. But I shot it [to be black and white]. Even though I’m shooting digital, in terms of lighting my highlights and the way it looked, it was designed to be black and white. I sent them a chair because I just though it could be used in a way that could be super beautiful somewhere. I had no idea that it would be that impactful.

The outfits that the women are wearing also help keep the photos visually unified— did you direct them in what to wear for the shoots?

I was not allowed to style anybody because the magazine wanted to keep it journalistic. The only thing that I requested was that they bring two outfits. One which is all black, and then one that is either all white, all cream, or very close to it. I did remove most of their jewelry, except things that seemed like they wore daily. I was scared about that by the way—you want it super chic, but I think that the color scheme, keeping it very consistent, and monochromatic made a huge difference. They all came camera-ready. Every single one of those women. There were certain ones that had a little bit more, or did a little bit more, but on their side. Not on our side.

You also directed the short videos that are part of the multimedia package—what went into setting those up?

Lights changed and background changed. I shot with four cameras. I put three cameras on sticks, and then I had another camera moving around to get closer, and more intimate. I like formulas. I need things to be exactly the same all the time. So when I have a blueprint, I stick with the blueprint. It was easy, once I figured out how I wanted the blueprint to be. The sound package definitely was one of the more difficult parts of the equation. At my studio there’s an ongoing train that literally was killing me. I’ve done videos in that studio, but never had to do a serious interview where their words were more important than my images. And you can’t stop somebody that is crying while talking, telling you really devastating shit to be like: “Oh, hold please. The train’s coming.”

I wanted to shoot the video the same way I shot the photos—so everyone had the exact same thing. What was also really important for me is that everybody introduced themselves, “My name is Janice Dickinson. I met Bill, or Mr. Cosby when I was blank old, in 19-.” I wanted to stop there and say “So what happened to you?” But it took awhile. When somebody that has been just told to shut up for so long is told go, they’re just all over the place. So you take in all of that, you take notes, and then you go, “All right. Now I want you to say that all again, but let’s formulate this.” Between that and dodging the trains, I definitely have 20 or 30 more gray hairs.

How long were you interviewing the women in the videos for?

Depends on the woman. I think the first couple of them I may have done like two hours. As I shot more and more, I knew what I didn’t want to ask, and what I didn’t care about. But those questions came from the magazine. They knew exactly what they wanted. I was there to augment it and facilitate it in a way that these women would answer it.

You’re often shooting portraits of people that you already know and have a relationship with, how was working with these 35 strangers different for you?

The difference is you’re more nervous before you meet them—you don’t know what you’re dealing with. I shot 35 different personalities, and it’s so interesting—when you shoot somebody, and then you’re talking to them, it’s a real connection. It’s kind of like a game in a weird way. It’s meditating yourself into that situation.

I’m onto the next, but I’m so happy it’s going off right now. It’s great working on something like that. That doesn’t happen that often.