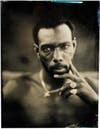

Matt Alberts’ 19th Century Skate Portraits

Last November Matt Alberts packed up an Airstream trailer with a portable darkbox, a massive camera, 4L of collodion, 500g...

Last November Matt Alberts packed up an Airstream trailer with a portable darkbox, a massive camera, 4L of collodion, 500g of silver nitrate, 1Kg of potassium cyanide and a few good friends. His mission: create collodion plates of people around the country who have dedicated their lives to skateboarding.

The first leg of The Lifers Project took Alberts and his crew along Route 66, through New Mexico, Arizona and California. A few weeks ago Alberts wrapped up the second leg of the Lifers Tour, traveling to the east coast to create even more wet plate portraits of skateboarders.

How did you discover the wet plate process?

I stumbled across the wet collodion process randomly because my ancestor did it. My third great grandfather was a wet plate photographer in Binghamton, New York. My whole life I’ve had plates of his, but I never knew how they were made. Skateboarding and photography have always been part of my life and I was feeling, as a professional photographer, frustrated with trying to make art with my digital images. They didn’t feel like they held much value really. I just felt like I was struggling to be creative with digital and I wanted to make something with my hands. I was missing the hands on, I was sick of sitting in front of my computer. I linked up with a guy named Quinn Jacobson who is in Denver. I took one of his classes, and it just instantly hooked me on the process. He is sort of regarded as one of the grandfathers of the process, he is the guru of it. He has an MFA in the process, and he literally wrote the book that I use, that most of Europe uses, I would venture to say that 60-70 percent of the people doing collodion today are using his recipes. It’s not like he invented it, but he modernized it.

So after you took his class did you just purchase his book, Chemical Portraits, and teach yourself?

Quinn recognized that I’m a visual learner and I had all this passion for this type of photography. He was basically like, I’m going to take you under my wing and he sort of just let me hang out at his studio and ask him any questions that I had. I was able to sit down with him for seven-eight months, help him teach his classes and apprentice with him. Then when it came to getting equipment he steered me in the right direction and showed me what to do and what not to do. He actually helped me realize what I wanted to do with it. There is a resurgence in these old types of photography, and there are a lot of people who are just kind of creating noise with it. They are not making art for the sake of any kind of meaning. People creating noise are just creating tin types because they like the aesthetic, but they don’t have any type of direction or artist statement or meaning—you’ve got to really be committed to take it outside of the studio.

Where did you get the idea for your project?

I am friends with a guy named Chet Childress who is a professional skateboarder. He is sort of at the end of his career, he has been around for a really long time and is still an awesome skater and guy. I met up with him in Denver and I was telling him about the process, he is an artist, and I was like, I’d love for you to come check it out. I want to make your portrait. The day he came over to the studio, was really when I came up with the idea for the Lifers Project. After listening to Chet and being with him—no body is more of a Lifer than that guy. That guy skates in the snow and the rain and in the sleet. Every single day he is on his skateboard, no matter what. I’m sure that he will be until he can’t walk or can’t for some reason. He is just that kind of a guy. I was like man, this guy is a lifer, and then I was like, wouldn’t it be cool to make photographs of people who have dedicated their lives to skateboarding.

When did you start skating?

I started skating when I was 9 or 10, and that was honestly, right around the time I started getting into photography. I started going to school right in downtown Philadelphia when I was 12. I’d take the train down everyday. The train was maybe two blocks from my high school and my high school was maybe a block and a half from Love Park, which in the ’90s was probably the epicenter of skateboarding. This was all before it was illegal, there was sort of a golden era there where it was illegal but they weren’t actually taking you to jail or enforcing it. So, here I am 12, 13, 14 I’d go to photography class and they’d go, “here is your camera, go out into the city and do whatever you want.” I was always around the city and almost always I had my skateboard and my camera.

What was it that made you want to document the “Lifer” community?

There is this stigma around skateboarding, at least there has been my whole life. In Philadelphia it is super illegal and when I was like 10, 11, 12 it would get me in trouble. Not because I was doing anything wrong, but because it was illegal to even do it. Your parents have the police call a few times to say that your son is in trouble for trespassing, when we were just skating … It would almost make any parent feel like skateboarders are criminals or whatever that stigma is. If you looked at Chet you might be like, whoa who is this guy, he looks fucking crazy and I need to keep my distance, and there is a lot of people like that in skateboarding. For me, I kind of made the connection there. Collodion only sees UV light one of the pictures of Chet—he has tattoos on his fingers and he is holding his hands in front of his face and you can’t see his tattoos because UV light essentially doesn’t see the top layers of your skin, it sees layers below. It feels to me that you are capturing the real person inside and you are exposing the person’s soul or their inside really.

Why do you think the skateboarding community has embraced the process you are using?

What people, especially in skateboarding have really gravitated to is it’s handmade, it’s me making it—if I mess up, if I put my finger on there, that’s there. In the picture of Chet, in the triptych, there are two from that day that are in focus, the third one was accidentally out of focus so then I let him just etch in the emulsion while it was soft with a screw. Sometimes I’m driving around with this stuff and I’m like, what am I even doing, it’s a huge pain in the ass. It’s six, seven boxes, and my camera, it’s a lot of chemistry and maintenance and it’s expensive, but people see the level of commitment that I have to my craft, photography and then also to skateboarding and they relate to both of those things. They relate to the handmade aspect. When you see me do it, anybody who sees it, sees the struggle, you see the amount of stuff, you see what it takes, you see the dedication behind it. The images themselves, collodion is just a beautiful format because it is grain less. Beyond the fact that it sees below the skin and it’s handmade, it is actually sharper then any other image on the planet, really. It’s crystal clear because it is made of silver.

Who are the people you are looking to photograph? What qualifies someone as a Lifer?

I’m going out of my way to involve not only big name pros, but the smaller guy who has made a bowl in his backyard, the guy who bought the house because of the swimming pool in the backyard. You don’t have to be a pro, you don’t have to make a million dollars, you don’t have to be Tony Hawk or Lance Mountain. Those guys in my mind they have contributed to giving back to skateboarding, but it has also been about the smaller guys, the kids building the DIY spot. We shot a guy, his name is Stubbs and he has a colostomy bag. He had some sort of infection and they had to take his intestine out. This kid skates around with a bag of shit attached to his stomach, literally. He didn’t care, he was like, “I was a little bummed at first, but the first thing I cared about was when can I skate again.” That’s how lifers think and feel about skateboarding. It doesn’t really matter what else is going on in your life, as long as you can skate.

What are some of your favorite plates that you’ve created during your two road trips for this project?

The one that I made in Two Guns, Arizona is definitely one of my favorites. All there is in Two Guns is a KOA building that is in rubble and then there is the swimming pool from the KOA building. We pulled up there, parked the airstream, got shit out, made lunch and skated the pool. I set up my camera, I poured a test plate, it looked awesome. I poured an 11×14 it came out perfect. I poured one more and that is the one that was in the show. Then we were out of there. To have it be like that, where you set up and it’s perfect is—it’s crazy, especially when you are doing the on location stuff. It almost always takes more effort than that. Sometimes when it is just right, it is just right.

But it sounds like most days aren’t that perfect?

The ugly days, it’s all you can do to not smash your camera and throw it into a river. Before we left New York, we were waiting for the rain to stop so we could make a plate of New York. I got up at like five in the morning I set everything up, I mixed my chemistry and I took a photo of my setup, posted it on my Instagram and got like a bunch of likes. Then I couldn’t make a single plate. The sun came up weird, it was direct sunlight coming through the lens and every plate was just coming out fogged. That’s the perfect example, I really didn’t realize that the light was going to come up that way.

You recently wrapped up the second leg of the Lifers Tour, showing the work you shot on your Route 66 tour and photographing more lifers—how did it go?

The new collection, I’m calling it the Brotherhood Collection. We left May 5 from Denver we went through Nebraska down to Kansas City down to Arkansas, through St. Louis, through West Virginia, into Philadelphia. We made plates in Philly for a couple days and then we headed up to New York. Along the way we were touring all the pieces from the Route 66 trip that we did in November. The plates look different before they are varnished, they go through all these different stages. I think that’s part of the reason we were so successful, especially in New York, a lot of people had come to the show and saw it and then they were like, “man I want to be apart of this.” Almost to the point that it was, eh we’ve got to take it easy today, we can’t have like 100 people coming through. We got 70 percent of the legendary New York skateboarders who have made the scene in New York what it is: Ishod Wair, Ernie Torrez, Danny Cepa, Spencer Fujimoto…

What’s your end goal for Lifers? Where do you see the project taking you next?

I want to go out and do Portland down to Los Angeles. The amount of trips could almost be limitless to some extent. It all revolves around funding. I really want it to be my contribution back to skateboarding. Skateboarding makes very few people actual money. I’ve never been out for the money, my goal if I could would be able to make enough money to fund it and then whatever extra there is, be able to give that money back to the skateboard community. The people who we involve, they’re not just in it for the money, they are in it because they want to skate. The money comes second. That is sort of a reoccurring theme for all of the people that we’ve had involved so far, some of them make money, some of them don’t, either way they are 100 percent skateboarding.

Do you feel working on The Lifers Project has changed your relationship to skateboarding?

As you get older and you have a job and stuff to do skateboarding winds up becoming something that is secondary to you. Maybe you are skating once a week or something. Lifers allows me to skate every day and hang out with friends of mine and meet all these new friends. If I can skate and make photos every day that’s like all I want to do. That’s easily been the best part. I don’t want it to end. I want it to keep going.