Ash Thayer on Capturing the Squatters of the Lower East Side

When young punks ruled Lower Manhattan's deteriorating buildings

Ash Thayer was a 19-year-old art student when she found herself suddenly homeless after an eviction from a New York apartment. With no family nearby and no means aside from the money she had borrowed from the government to attend school, Thayer found herself crashing at See Skwat, one of the many deteriorating buildings on Manhattan’s Lower East Side that had been abandoned by the city in the ’70s and eventually taken over by low-income residents with no where else to go.

Thayer says she bounced between the city’s various squats between 1992-1998 as she worked on finishing her degree at SVA. She documented her day-to-day experiences in the environments as a way to both fulfill her class assignments, but also to create a visual record of the sweat-equity that residents had poured into these buildings that had essentially been left to rot—in case the city tried to evict them.

“I was learning to develop film while I was photographing all of this. Some of these rolls of film were the first ones I was developing,” Thayer tells American Photo. “Obviously I kick myself—I wish that I had the technicals skills then. I would have had four books to fill up.”

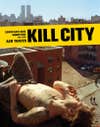

Many of the images that did make it through her camera intact have been collected in a new book Kill City (released last week powerHouse), which we named as one of Spring’s best new photobooks.

Thayer spoke to American Photo about her days as a New York City squatter and the challenges of documenting subcultures in an intimate and accurate way.

You were an art student when you started living in See Skwat in Manhattan—how did you end up staying there?

I didn’t know what squatting was until I got to New York, but I knew a lot about social activism, the history of anarchism, and civil disobedience. I ended up needing a place to live because I couldn’t afford to live in Manhattan. I got kicked out of an apartment and they kept my deposit. I was already hand-to-mouth—living on student loans—I literally had no place to live. The only reason I could pay for school is because I was borrowing money. I was already going to punk shows, hanging out with kids in Tompkins Square Park, drinking lots of beer…

I moved into See Skwat because I had no money—it was financial, it was survival. As I started living there I found out about the whole community. I kind of went in blind. I knew enough: we had taken over this city abandoned building and we are building apartments. I could do work in exchange for a place to stay. I learned, but it was trial by fire.

Were you interested in the punk scene before you moved to New York for art school?

I got into punk rock because I was very much picked on and bullied. I was kind of nerdy and awkward. I was beat up by cheerleaders—literally—like “Mean Girls” part two. It really messed me up, I had emotional issues and depression in middle school.

I got really into punk rock culture when I was 16 in Memphis. My last year of high school I moved out of my family’s house and moved into a punk rock girl house. I went to this public school with a great art teacher and he told me to pick up the camera. I just started photographing my friends and the punk scene, because that is all I really cared about. The punk community was my safe place. It was a place where I could be myself and I could have a normal kind of social life.

What was See Skwat like when you first moved into it?

It was really dimly lit, there were a few lightbulbs in the hallways, some of the stairs were falling apart, some had already been replaced. It was pretty shitty, except for what people had started working on. [In the photo of] the community room, you can see toaster ovens stacked over in the corner to the right, a little bit of a sink thing happening. This is before there was running water there. We would get water from the fire hydrant and fill up these jugs. Then we would have buckets under the sink for water to go into and then we would have to empty that out. It is such a long process to rehab a whole building—when you are putting in floors and a roof and walls that takes months.

When I lived there in the ‘90s people were working their asses off everyday. What I saw was people without means, coming up with their own means and being very empowered with the little bit that we had. We created stuff out of the crap that rich people threw away in New York: furniture, sheetrock—we salvaged everything.

In the book you mention that there was always this fear of eviction and that you saw many of your friends lose their homes to these illegal evictions—what were some of the tactics that squatters used to avoid eviction?

We were on constant lookout for any signs of eviction. One sign would be they would put a dumpster in front of your building so they could throw all of your worldly possessions into it and clear it out. They put a dumpster in front of our building, it was actually for something else, but we were so freaked out so we started barricading all the doors. We stayed up all night doing it. That is what you had to do when you thought there might be an eviction. You could actually keep people out long enough for them to either give up or to raise such awareness that you could buy yourself time and then the city wold have to figure out how bad they wanted you out.

The city should not have been financially responsible for evicting squatters, but Giuliani was such a steam roller he would go in and evict and put it on the city’s tab. It should have been by the private investors who were trying to buy and develop—it was there obligation. He paid millions of dollars of tax payer money to get these people out who had cleaned up these blocks, cleaned up the buildings, worked for years on them to make low income housing just so private developers could come in.

When you started photographing the squatting community were you interested in documenting the culture, or was this more about photographing your daily life?

I never really had a plan for my future. I was not thinking of a career path then—I was very much in the moment. I was so desperate for my life to have meaning and purpose, which is why I was so interested in social activism and protest movements and fighting against injustice. This was all of those things. And I was able to fulfill my requirements in school by taking these pictures—although I didn’t get a lot of encouragement in school for this work.

What sort of feedback were you getting from professors and peers when you were making this work?

They thought I was talented, and that a lot of the pictures were strong, but in general people had a really dismissive attitude toward the subject matter. People couldn’t eroticize dirty punk kids. I feel like it didn’t fit into a category of shocking brutality like Nan Goldin, whose work I obviously love, but I was interested in these people—the humanity of my subjects. They were, in my eye, of more worth and more interesting for me to look at then fashion and commercial work. This was my version of beauty and worth and meaning and purpose. I felt passionately about who I was photographing and what was happening, but I didn’t have the strategy—I was just doing it.

Many of the buildings you stayed in had either no electricity or limited electricity—what were you using to shoot in these buildings that were essentially construction zones?

I had a Leica M4P with a 50mm lens with Kodak VC 400, Tri-X 400 and some TMax 3200. Raghubir Singh was one of my real influences and he actually gave me a flash because I was to poor. He said, these interiors are so dark you really need to shoot with flash and he gave me a flash— he was a very powerful mentor for me.

Aside from Nan Goldin and Raghubir Singh, who else was influencing you at the time?

I also had Joel Meyerowitz looking at some of this work, I didn’t spend a lot of time with him but he did a studio visit while I was in graduate school. I was influenced by Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus—Helen Levitt was my jam, the lyrical quality of her work. Also just the beauty of these kids doing so much hard labor. I just thought that was utterly fascinating to watch and be a part of. I would be doing construction and then I would stop and pick up my camera and take some pictures and then I would go back to doing it. The Leica is very easy to swing around your neck and throw over your shoulder, so it just went with me everywhere.

Many of the portraits in Kill City capture these quiet moments and were taken inside these sparsely furnished bedrooms, with great light. Why was it significant to shoot your subjects in this way?

We did a bunch of activism and hardcore things, but at the end of the day we were these young vulnerable kids trying to create safe spaces for ourselves. Not just a roof over our heads, but emotionally safe spaces, where we had community and love and friendship. Most of the kids I lived with were runaways, came from bad homes or had troubled youth experiences. It was this mutual sort of sharing of vulnerable moments. On the street [people saw us as] street hustlers, trouble makers, vandals—that just wasn’t really the case. We were hanging out, drinking and watching 90210 around one TV, like 15 of us. There was this sense of innocence there. I was let in to these times and people were able to be vulnerable around me.

Looking back, what do you think was the most challenging thing about making this work?

Just being a beginning photographer. I was learning to be a photographer throughout this process and you know [dealing with] low lighting, fast moving action, also just wanting to be careful about how I was representing people and not wanting to make work that looked like other people’s work. I was aware of Nan Goldin, Larry Clark—those were the good ones—but there is a lot of bad photography out there of people attempting to photograph subcultures that they weren’t apart of. My biggest challenge was making authentic images that would honor my subject matter and represent my feelings.

Kill City is available from powerHouse Books.