Gordon Parks’ return to Fort Scott

“My sense is that if it had run it would have been a very nuanced photo essay.”

Years before Gordon Parks’ well-known photo essay “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” covering segregation in the deep south was published by LIFE Magazine, the photographer was working on a much more personal story about a similar topic.

In 1950, only two years after he had been hired as the first full-time African American photographer at LIFE, Parks was sent on assignment to his birthplace of Fort Scott, Kansas, where he had attended an all-black school, to cover the story of school segregation through the lens of his eleven former classmates. But when Parks arrived in Fort Scott he learned that all but one of his classmates had moved away, in search of a better life and an escape from the poverty and discrimination they had all grown up with. The story, which he planned to call “Back to Fort Scott,” instead became focused on the Great Migration and over the course of a few weeks Parks tracked down each of his former classmates and photographed them in their homes. The photo essay and article were slated to appear in the April 1951 issue of LIFE, but then for reasons that are unclear the entire thing was scrapped.

Parks moved on to other assignments and for many years this particular collection of work sat unseen, but now a new exhibition, “Back to Fort Scott,” organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Gordon Parks Foundationis bringing together these photographs and text for the first time.

“My sense is that if it had run it would have been a very nuanced photo essay,” says Karen Haas, the curator behind the exhibition. “This is a time when, as a black person, you wouldn’t necessarily look directly into the eyes of a white person walking down the street. To look into the eyes, in a sense of 20 million LIFE Magazine readers, that was quite brave and it was quite a powerful statement.”

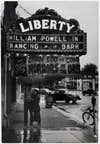

Haas says the exhibition came about because of separate research on a Gordon Parks photograph titled “African American Couple in front of Segregated Movie Theatre,” that was already owned by the museum. While working with the Gordon Parks Foundation, Haas discovered that the image had been made in Fort Scott, Kansas and was introduced to this mostly unseen body of work.

“I was fascinated by the idea of this photographer, who is well known, whose work is so well researched and here was this opportunity to show this work that hadn’t really seen the light,” she says.

Research for the show began a year ago and Haas describes gathering the information about each of the photographs as feeling a bit like detective work. All of Parks’ photographic archives are housed in SUNY Purchase in New York, but anything text based is held within Wichita State’s archives. Through this triangulated research process Haas discovered that many of the pictures hadn’t actually been made in Fort Scott, as was originally assumed, but in cities such as Kansas City, Saint Louis, Columbus, Detroit and Chicago.

“The most interesting thing for me was this idea that he goes to this place, he talks about the importance of this place, his childhood experience, his own segregated school experience,” she says. “Then he very quickly takes to the road and finds these people one after another and sits on their porches and in their parlors, talks to them and photographs them. That became the organizing principal of the show—this sort of road trip idea.”

Parks captured his former classmates mundane every day moments: Relaxing on the porches with family, playing games of pool or heading to church on Sunday. The images were archetypal of the kind of work the mostly-white LIFE Magazine readers were accustom to seeing: pictures of people with middle class aspirations, people who were just like them. “He had an amazing knack for blending in and stepping back and making people relax,” she says. “Staying with it long enough that people let down their guard and were very natural with him.”

“Back to Fort Scott,” is the fourth exhibit organized by the Gordon Parks Foundation that has deeply examined an individual LIFE Magazine story that the photographer worked on. Each exhibition is accompanied by a book and earlier shows have been held at the Studio Museum in Harlem, the New Orleans Museum of Art and Segregation Story is currently on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. But this is the first exhibit and book to be created without the “blueprint” of an already published story.

“There was something sort of scary and liberating realizing that there was no layout,” says Haas. “Everyone else who has written one of these books has had an article or a photo essay to critique—I didn’t have that safety net.”

Although Haas lacked the same hard structure available to earlier curators there was still plenty to learn from the raw materials her research provided her. Especially considering that Parks is a photographer whose personal history has always been wrapped into contextualizing his work.

“I really think that it was the experience of going home, taking stock and measuring how far he had come—both emotionally and geographically— that really inspired him to go on and do a lot of what he was able to do later in his life,” Haas says. She also notes that when viewing this earlier work alongside his more well known story “The Restraints” from 1956, the influence is undeniable. The picture of two African American girls watching a baseball game through a chain link fence alongside a group of older white people is particularly telling for her, especially when viewed alongside a very similar picture he made in 1956.

“It’s the type of thing that Parks, as a black man, would have recognized and children that young would have realized,” she says. “To see this other [1956 color] picture, of these kids looking through a fence at something that they are not allowed to enter because they are black—it really just knocked me out. Like okay, ‘I didn’t get to run this the last time, but I’m going to make this point one way or the other.’”

Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston from January 17 through September 13. A book of the same name, published by Steidl will be available in mid-February.