Glen E. Friedman on the Golden Eras of Skateboarding, Punk Rock, and Hip Hop

Glen E. Friedman has spent the last 40 years creating the iconic images often associated with skateboarding, punk rock and...

Glen E. Friedman has spent the last 40 years creating the iconic images often associated with skateboarding, punk rock and hip hop and his new book, My Rules, brings an incredible collection of photographs from his archive together in one massive seven-pound tome.

Friedman spoke to American Photo about combing through his archives, capturing counterculture movements and the never-before-seen gems that initially slipped through the cracks.

The photos in My Rules span your entire career, when did you start editing?

Probably 80 percent pictures from the Fuck You Heroes book are in this book and I knew they were going to be in this book. The beauty of it now is they look cleaner than ever because of the modern [scanning] technology and they are bigger than ever. A lot of [the editing] was done because of the previous books, so I had a big head start, but the actual edit for this book—at least 3 years ago. There are images that fall through the cracks. I tried looking under every fucking crack I had. In between every slide page, over and over when I would go back to my archive in California. Every trip, I would try to go through another binder full of old slides. Even the old boxes of old slides that I would put in the shit pile. Sometimes stuff just falls through the cracks and you don’t know. There is definitely some good stuff in this book that originally fell through the cracks. There will be new iconic images that people never saw and they won’t believe that they haven’t seen before.

What are some of those images that had initially slipped through the cracks that people will finally be able to see?

There are a bunch that are in this book that I hadn’t seen or I had forgot existed. From a roll of film that I shot for Public Enemy’s second album—the greatest hip hop album of all time, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back—I shot one or two rolls to get that cover and the proof sheet was made in such a way that a couple of the images looked really blown out. When I finally went back in this process and looked at the negatives they were fine. Here, we have a photograph in the new book from that session that is better than any photograph that anyone has ever seen. The composition is more perfect. Just everything about it is more interesting to me and there it was, I just scanned over it on the proof sheet for many years because it was blown out on the proof sheet. One of the opening shots in the book of Tony Alva—a beautiful shot where there is a refraction of sun in the lens and just a touch of a rainbow and it’s stylish and great—is a photo I don’t even remember ever seeing before. I don’t know how I skipped over it.

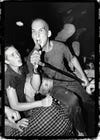

There are Black Flag shots from the time they were recording their first album. They were just standing outside the studio in the rehearsal space where they were recording the Damaged album, here are photographs from that day that no one has ever seen before—it’s great. Really young Henry Rollins, one tattoo, so proud to be in Black Flag that he is actually wearing a Black Flag t-shirt himself. That is not something you would see him do a couple of months later.

Some of the photos in My Rules are 40 years old. Did you see different things in them as you dug through your archives?

When you first take the photos you are looking at something very specific that you have to say in the image. People don’t know these people yet, so you really have to express a lot of different information. Like I said, 20, 30, 40 years later, people know these people. You don’t have to tell every facet of the story in the 1/500 of a second. Now, you can concentrate on other parts of the story so other pictures come alive that at one point weren’t alive to you.

This book has the same title as a zine you put out in ’82 — is there a connection there?

Originally the book could have been called Fuck You All, like my show that has been traveling around the world for the last 15 or 20 years. “The Fuck You All” show was really combining the best of Fuck You Heroes and Fuck You Too into one big show, and this book was kind of like that. When I first made Fuck You Heroes, saying that on the cover of the book was a very bold, very progressive, very radical thing to do—20 years later, not so radical. It was becoming kind of gimmicky and I didn’t want to go that route again. I can’t just live on that forever. I wanted to go back to the roots, My Rules is really where it all comes about. My Rules is really a suggestion of integrity.

The new book includes essays written by many of your subjects. Why was that important to include?

The original My Rules I asked the guys to write their own ideas and things they wanted to express to the punk rock community of the time. In this book, I asked a lot of my subjects to also write something, but I was more specific this time. This time I’ve asked people to write about their inspiration that got them to the point to where I was photographing them. I’ve got some unbelievable words from people talking about that time. You can be brought to tears by some of the essays. Some of these guys have such hardened shells, this many years later, but to get them to open up as I did for the book, it was inspiring to me.

For me, I live with the photos every day and I love them. They all still inspire me to this day. Every one of these photos in this book I still love, but seeing the words every 12-18 pages sprinkled in between there, it is awesome. That word can be overused these days, but to me it really is. LL is talking about living in his grandmother’s basement when he already had gold records. Adam Horovitz talking about his brother and his sister inspiring him. Tony Alva admitting that he was afraid of the water. A born and bred surfer, admitting he was a little bit afraid of the ocean, intimidated sometimes. There are some real incredible stories in there.

It’s obvious that you were an active participant in all three of these subcultures, what do you think that adds to your images?

I think being a skateboarder, being involved in the punk rock scene and the hip hop scene—heavily immersed in them—makes all the difference in the world. That is what makes my work. Being associated with the subject to the degree that I was is what makes it vital. These subjects deserved this attention from me. It’s the subjects that inspired me. Hopefully, because I cared so much about the work and the artists cared so much about what they were doing, it will draw you in and you will want to look deeper into it.

My work is all about inspiration. The inspiration I got from the artists I am trying to show in a respectful and meaningful way. The way the Renaissance and classical artists would paint a painting is how I want to take a picture. You can call it a snap shot, and it certainly is a moment in time, but much more goes into it.

How do you see these three subcultures as being connected?

It’s really obvious to me. It’s really all about the attitude. Every one just has the same bad ass attitude. There are so many more skaters and punks and hip hop enthusiasts than there were back then, but it’s that same badass attitude that attracts people. Some people got it and some people just want to bask in its glow, you know? It’s that rebellious spirit that attracts everyone to these subcultures.

What kinds of things do you look for when making an image? What made a shot a keeper?

If there are people in the photograph the most important thing is to get their character and some kind of emotion, some kind of attitude. People sometimes think emotion is big smiles or tears. It’s not just that, it is also attitude. Attitude is a very big part of it: character, composition, clarity, exposure and focus—those things are a given in my work. The environment in which the subject operated is also very, very important.

What gear were you using at the time?

I grew up on Pentax equipment and I use it to this day. I used a Pentax KM I think and then I got a Pentax MX because it was the smallest 35mm camera made at the time. I wanted something small because I was a skater and I wanted something less cumbersome. Also the MX got me, which was invaluable at the time, a motor drive to get a sequence. The K1000, when it came out, was just my favorite camera. Honestly, it is the camera that I use to this day, it is the camera of my choice. Different lenses over the years become my favorite lenses, for a very long time. For a lot of my early music stuff it was the 28mm lens and when I was still using a flash, 28mm f/2.8. During the skateboarding years I used almost exclusively the Takumar 17mm f/4. It was head and shoulders above every other lens and wasn’t bulky. The 17mm f/4 only stuck out an inch from your camera and had the filters built into it. It was an incredible piece of glass. When I got more into shooting bands the 15mm f/3.5 became a real favorite of mine, but it was a real bulky piece of glass, so my compromise and go-to lens probably for the last 25-30 years has been the 20mm, f/2.8 and there is also a 20mm f/4.

What films did you favor back then?

I always loved Kodachrome 64. When Kodachrome 200 came out, I loved that too and that became like my exclusive go-to color film. It was natural real color. All these vibrant, over-saturated Fuji films—that’s fine, if I was shooting surfing or something, I would do that. But generally I liked the realness of Kodachrome and it was a very sad day to me when it was ended. I remember I shot my last roll very carefully and I actually wrote an article about it for Skateboarder Magazine. Kodachrome was real special. Tri-X to this day is still a favorite.

I liked that the book is a mixture of your old and new work: new shots of Keith Morris in OFF, new shots of Lance Mountain skating the pool at Chelsea Piers…

I still shoot skateboarding even now, every once in a while. If I’m inspired then I’ll shoot. Shooting my old buddies skating now? Meh, it’s not so inspirational. It’s like, you guys were better when you were young, and I’m happy that you are doing it now, but for me to take a photo of it—I mean, someone like Jay Adams I would probably still photograph but we are old men now. We don’t need to be photographed. And for the young kids that need to be photographed—their peers should be shooting them.

I am inspired occasionally by some of my old friends, I’m just saying I don’t need to go out every day and shoot them. OFF is a great band. I can shoot Keith Morris in OFF, but would I shoot him in the Circle Jerks? Maybe? Maybe not. But OFF is like a new entity and they had a lot of energy. The other thing about shooting the OFF gig is they were in a record store. It had a lot to do with the setting too. That was all inspiring. What the bummer was, is there were so many other people there taking pictures and there is a guy whose camera is in my frame. Sticking his camera out—that is a pet peeve on mine—not looking through the camera. I hate that.

What are other pet peeves, things you see music photographers doing today that you wish they didn’t?

Getting in the way of subjects, getting in the way of other photographers and getting in the way of the audiences. Just because you have a camera you think you are the most important person there? Actually you should be the quietest person there and you should try to be unseen. I eventually stopped taking flash photos at shows because I just wanted to use the ambient light and I also started noticing, as I was getting older, with a flash is going off, you’re getting more attention than the subject. Fuck that—that is not proper.

Glen E. Friedman’s book My Rules (Rizzoli) is out today. Purchase your copy here.