Books of the Year: “The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott”

In November 2010, Captain Robert Scott and his crew on the Terra Nova set sail from New Zealand for Antarctica,...

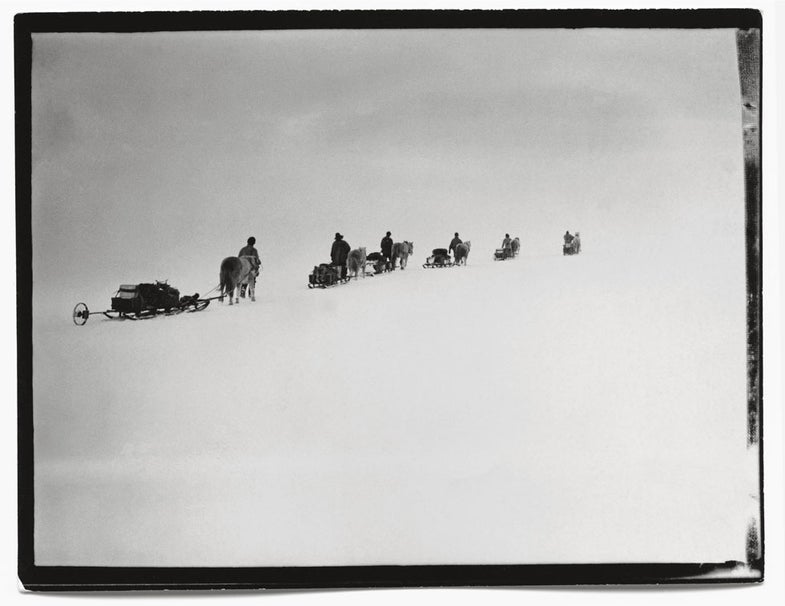

In November 2010, Captain Robert Scott and his crew on the Terra Nova set sail from New Zealand for Antarctica, in hopes of being the first explorers to reach the South Pole. After a complicated journey involving countless setbacks, Scott and four companions did reach the pole in January 1912—only to discover that a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had beat them to that destination by 33 days. Worse, due to exhaustion, extreme cold and starvation, Scott’s team perished on their return journey.

Months later, a search party discovered Scott and his fellow explorers’ remains and belongings. These included many valuable records of their harrowing journey—including a number of photographs. Scott had hired a professional photographer named Herbert Ponting to document the expedition, but during the journey, Scott learned how to expose the 4×3.25-inch glass plates himself using Ponting’s custom-made, cumbersome view cameras and tripods. Ponting left the expedition before the South Pole push, but Scott continued to shoot images until the end. Somehow, these negatives recovered among Scott’s final possessions managed to slip into oblivion for the better part of a century.

But no longer. In The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott: Unseen Images from the Legendary Antarctic Expedition (Little, Brown, $35), polar historian David M. Wilson reveals the rest of the story — as well as many of the remarkable images Scott captured on his ill-fated final push. In 2001, a set of these photographs were quietly auctioned off at Christie’s to art collector Richard Kossow. A few years later Kossow met Wilson — the great nephew of one of Scott’s crew members — and this book was conceived. “Without his foresight in acquiring the Scott photographs,” Wilson writes of Kossow, “and his eagerness to share them with the public, they might have been lost forever.”

We recently checked in with author Wilson to discuss the scholarship, and passion, behind this historic volume, one of our photo books of the year.

Jack: When did you become aware that the photos in this book were indeed attributed to Captain Scott? What was your entry point?

David: It started over a glass of gin and tonic with some polar collectors in a bar. A gentleman asked me if I could guess what he had in his collection. When he told me I nearly choked on the lemon. I saw the photographs two days later and their authenticity was quite clear. They were all marked with S numbers, S for Scott, some with the handwriting of the official expedition photographer, Herbert Ponting. I did some simple double checking with some quick research to cross-reference the handful that had been published at the time. Remarkable! And very exciting to see so many long-lost and unseen images.

Scott’s photographic role is described as an extension of his hand-illustration efforts on earlier voyages. Did he know he was documenting history?

Of course Scott knew that he was documenting history — he was an explorer in the richest sense of the word and that is what they do: make records, maps, and collect scientific specimens. Explorers, good ones at any rate, do not simply dash from one place to another listing “firsts,” they extend the frontiers of human knowledge. Scott was a modernizer; he was interested in making better scientific records than had been done to date and pioneering the role of the camera in the exploration of the polar regions. Scott’s deployment of the first professional photographer, Herbert Ponting, on an Antarctic expedition was groundbreaking and it marks when the camera succeeded the sketch pad as the best means of recording polar expeditions. Scott had himself trained as a photographer to make sure that the South Pole journey, one of many exploratory parties sent out by his expedition, was properly recorded.

What was the most unexpected discovery that you came across in the research and writing?

The photographs themselves! They reveal an artistic side to Scott that has not been documented before. My favorite research moments, however, were when I was able to match my great uncle’s sketches with Scott’s photographs. My great uncle was the expedition artist as well as Chief of the Scientific Staff and several of his topographical drawings enabled identification of Scott’s photographs.

This is a very detailed account. How much time and effort went into the research of the expedition?

I have been researching and lecturing about the expedition for some 15 years now. This book took about five years of work — not full time, as I tend to work on several projects at once — but they all interlink and feed off each other.

You point out that Scott was not afforded the luxury of self-editing photos, diaries, etc. In retrospect, did you feel compelled to make your own edit? Or was this a warts-and-all portrait of what happened?

I never whitewash anything — I stick to the archival evidence and try to keep things in context. The stories are exciting enough without having to make them up and I have never found anything worthy of whitewash, having been deeper into the archive than most. What on Earth would you hide a hundred years later anyway? Many contemporary criticisms of Scott tell you more about their authors than Scott. The malice of criticism for criticism’s sake (it is supposed to sell books) could be leveled at any explorer of the period and it is easy enough to twist and make up ‘”evidence,” but that’s sloppy research. Parts of this book may sound quite radical — as it is a return to some basic facts which people have forgotten, along with the photographs. For those, there is a full catalog at the back.

For amateur work, these are compelling images. Many landscapes are deliberate, and beautiful, atmosphere shots. How seriously did Scott take his role of photographer?

Scott took photography very seriously. He was among the most enthusiastic of Ponting’s pupils. Scott had become so excited by what Ponting was achieving with his camera he asked Ponting to teach several officers in the proper use of the equipment. This book charts Scott’s progress from beginner to a camera artist worthy of his teacher through his own photographs. It is an exciting journey that provides an interesting parallel, almost a metaphor, to the Pole Journey itself.

_In January 2012, many of these photographs will be on display at the Natural History Museum in London, part of a centenary exhibition on Captain Scott, which runs through until September. _