No Two Alike?

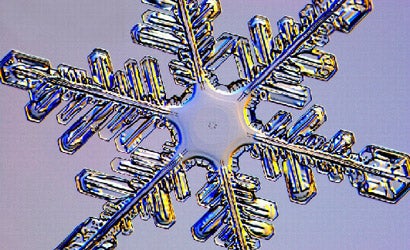

Scientist and photographer Kenneth Libbrecht finds grand beauty in tiny snowflakes.

Having made more than 7,000 pictures of snowflakes, Dr. Kenneth Libbrecht is in a pretty good position to say each one is unique. “People make a lot more out of that saying than they ought to, you know,” he says with a laugh. “I’ve addressed that on my website, snowcrystals.com, in all it’s gory detail, just for the record. And as I like to say, the question of no two snowflakes being alike depends on what you mean by snowflakes and what you mean by alike.”

Libbrecht does opine that he has never encountered two identical snow crystals through his microscope. A scientist and a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, he took up what he calls “the ice project” in the late 1990s and began making photographs of snow specimens as an avocation. “Since we don’t have snow in Pasadena,” he says, “I get anxious to go somewhere and look at the snow — at least once or twice every year.” Four of Libbrecht’s pictures were selected by the United States Postal Service as designs for stamps in the winter of 2006. And he has published four books of his luminous crystal images, most recently a coffee-table volume called The Art of the Snowflake (Voyageur Press, $30).

In his new book, Libbrecht explains some of the technical aspects of his craft: He travels to very cold locales for specimens and gathers flakes on a black foam-core board, then gently brushes them onto slides. “Once a crystal is under the microscope,” he says, “I have anywhere from a few minutes (on colder days) to a few seconds (on warmer days) to adjust the lighting, focus, and take the shot.”

Libbrecht readily admits his debt to the original pioneer of snowflake imaging, Wilson Bentley, who photographed snowflakes from 1885 nearly to the time of his death in 1931. “Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty,” Bentley wrote, “and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others.”

Yet Libbrecht has brought this art form into the digital age, connecting his microscope to a Nikon D1X, shooting richly detailed images, and analyzing the crystals (see slide show for details). “I developed the art a little bit,” Libbrecht says. “Bentley got it started — but it’s surprising to think how few people have done it in the last hundred years.” We recently spoke with Dr. Libbrecht about his ongoing scientific and photographic passion.

Jack Crager: How can you focus on something like snow and live in Pasadena?

Dr. Kenneth Libbrecht: I like to say it’s easier to appreciate snowflakes when you don’t have a shovel in your hand. I sort of got into it from the science end. I started to study how crystals grow, and looked at ice as an interesting crystal. And I started reading about it and doing stuff in the lab and I got into the photography. It’s sort of funny, living in Southern California, but I figure it’s like photographing whales or polar bears or something — I just go to where they are.

JC: The closest snow to where you live is in the mountains of California?

KL: Yeah, I’ve done that. I’ve gone to Sequoia National Park and Tahoe, but the crystals aren’t so good there — it’s too warm. Even in Vermont, it’ a little too warm on average. The best snowflakes you get at around 5 or 10 degrees — that’s pretty cold. My favorite spots are in Northern Ontario and Alaska.

JC: What does your family say when you make these trips?

KL: A lot of times they go with me. My wife always wants to go with me. Our two kids get a little bored with it [laughs].

JC: As a scientist, you started in solar astronomy, right?

KL: That’s right. It was bit of a change. I had been working on studying the oscillation of the sun, it was called helialseismology. And, I don’t know, I just felt that we had covered it. It was time for a change. So I looked around and played with a few other things and sort of happened into “the ice project.”

JC: How did you get into the photography part of it?

KL: Well, I started by looking at the physics of it, but as I started reading about snowflakes, I found it fascinating. So I thought I would write a book, and of course you couldn’t write a book without the photographs. And at the same time, I had been working in the lab and trying to photograph the crystals we were growing, and so I’d developed these microscopy tools, and put two and two together and realized if you made a really nice microscope with a digital camera and illuminated the crystals with colored light, you could get some spectacular pictures. And nobody else was doing it, or hardly anyone was.

JC: This was after the advent of digital?

KL: Yeah, I don’t play much with film. Film is a pain in the neck [laughs]. And these kinds of pictures are much better with digital.

JC: You quoted [snowflake-photography inventor] Wilson Bentley in the book. How much were you influenced by him?

KL: When I started thinking about physics and about writing a book, I went looking for pictures, and Bentley’s pictures were still like the standard. That was almost all you could find. And of course the pictures were a hundred years old. And they were taken with really lousy equipment, by modern standards. He did really well with what he had. But the idea that that was the standard, today, was sort of silly. So that made me realize that if you took some good pictures, you could do something with them.

JC: In your new book you describe the process: using a piece of foamcore to catch the crystals and brushing them over to a slide. How can they stay intact while you’re doing that?

KL: Well they’re small, but they’re fairly tough. But you have to be careful. I pick them up with a little paintbrush, very delicately, and drop them onto a little slide. It’s all done outside — it’s very cold. And they manage. Sometimes I’ll break one, but there’s lots more where that came from.

JC: Do you plan to keep working in this realm awhile?

KL: Oh yeah. I went out just a few weeks ago to Northern Ontario and got some nice pictures. Every snowfall will bring something a little different, and every snowflake is different.

JC: So these things are truly unique? You’ve sort of qualified it, saying only the complex snowflakes are one of a kind.

KL: Well, people make a lot more out of that saying than they ought to, you know. No two grains of sand are exactly alike either, but nobody really cares about that. But the physics is really interesting, and I’m just scratching the surface on the physics, so I’m definitely going to keep studying it for awhile.

JC: How does this tie in with your work at Cal Tech — do you teach it?

KL: It’s not a class per se. It’s not broad enough to be a class. It could be a little special topic in class sometime. It’s my main research direction now, and it’s good physics. But when you teach you’ve got to teach freshman physics — you know, mechanics and electromagnetism. The frontiers of science are very specialized, whereas the stuff you teach in classes on is still pretty general.

JC: Do you see yourself teaching about photography?

KL: No, I’m an amateur [laughs]. I guess I’m not an amateur, since I get paid for it. But I’m not an expert. I’m kind of an expert on snowflake photography, I guess.

JC: Do you shoot about other kinds of subjects?

KL: Well, a little bit, but not much. I like to kind of stick to ice. I like to photograph ice formations, winter scenes, things like that. I include some scenery pictures in the books. But other people do landscapes much better than I do.

JC: Do you have plans for more books?

KL: Yeah, we have another book coming out next fall, yet another snowflake book [laughs]. It’ll be a gift book. People like this stuff around Christmastime. There’s only so many angles you can take on it — and I’ve covered most of them — but there are always other angles.

JC: Or you could switch over to photographing sand.

Other people have done that.

JC: These crystals actually do form around dust particles in the air, right?

KL: Pretty much. The other alternative is, you could have two snowflakes that collide and they will chip off a little piece of ice and that will start a snowflake growing. But that’s unusual. Mostly they form around dust. In fact, if you look up at a cloud, a cloud is made of water droplets, and virtually every droplet has a piece of dust in it.

But on your sand thing — it’s true that other people have done this with sand. In fact, there are people who collect sand. You can go on eBay and buy sand samples. There’s black sand, red sand, green sand…. It’s a funny thing to collect, but there are a surprising number of people out there who collect sand. I think I’ll stick with snowflakes.