Behind the Scenes on Hollywood’s Biggest Movies

Photographer David Strick documents the art of filmmaking in a most unusual way.

In the entire history of Hollywood photography, no photographer has ever documented the craft of filmmaking the way David Strick has.

There have been many notable celebrity portraitists, from George Hurrell to Herb Ritts, who have captured the glamour of movie stars. There also have been many photojournalists, from Henri Cartier-Bresson to Douglas Kirkland, who have documented movie making. But no one has done it the way Strick has been doing it for the past 30 years or so.

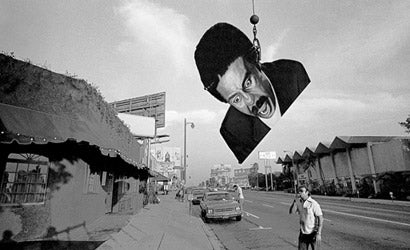

Strick’s images capture the often funny and sometimes poignant interplay between the reality of the filmmaking process and the fantasy of the movies themselves. These are the moments when the actuality of craft and creativity are transformed into what Strick calls Hollywood’s “industrial magic.”

“The end product of this process affects all of us so deeply, but no one ever really has paid much attention to the work itself,” he notes.

Strick published his first collection of images in the 1987 book Our Hollywood, and for many years his work was seen regularly in Premiere magazine. Beginning this summer he became a contributor to the Los Angeles Times with a weekly feature called “David Strick’s Hollywood Backlot”that can be seen both online and in the Thursday edition of the newspaper.

This publishing arrangement gives Strick a unique platform for his visual ideas and has reignited his career. He talked with American Photo recently about working in two media at once, as well as his singular vision of Hollywood.

American Photo: Not many photographers are given regular features by newspapers, so you really are breaking new ground with this new job.

David Strick: Newspapers and magazines have lots of writers who do regular columns, but this is a fairly unusual situation for a photographer. I think the most interesting part is working both for the newspaper’s online and print products.

AP: Why is that?

DS: The web is changing everything in our culture. Magazines and newspapers, where I have always published my pictures, are trying to cope with it. And the entertainment business is facing real challenges related to the Internet — diminished advertising, lower DVD sales, and piracy. I wanted to explore how the Internet could work in a positive way for all the sides I deal with.

AP: Please explain more.

DS: For one thing, the Internet has become very important for movie studios because of the way movies are marketed now. The whole idea of success now is based on opening weekends — if a movie doesn’t have a big opening, it’s going to be bad news. So generating attention to upcoming movies is the Holy Grail of all publicity efforts. About 80 percent of film reviews are now read online.

AP: That’s is an amazing fact.

DS: Also, the viral aspect of the Internet has been an essential ingredient in the marketing of movies. Studios start putting out trailers for films a year in advance of the release date. One of the advantages of early publicity like that is that the studios can take advantage of the viral aspect of the Internet. One of the first movies we featured when my column debuted in the L.A. Times was Twilight, which has a huge viral audience of dedicated fans from the books it was based on. The studios were very happy to get that early publicity from my project.

AP: Is it hard to get access to movie sets?

DS: Yes, even for someone with a track record like me. Studios and production companies are not interested in supporting somebody’s art project. They’ve got their own art projects to worry about. If you’re going to be on their sets, you’ve got to be able to show that what you’re bringing to the table is a positive thing for them.

AP: How did you take up photography?

DS: I was a typical high school photo geek. I took a picture that won an award from the Boys Club of America — it was probably the best picture I’ve ever taken, and I’m still trying to recapture that magic. Sad, isn’t it? I did a year at UCLA and later studied at the California Institute of the Arts, but I never graduated. I went to work at a startup weekly called L.A. Newspaper, but it only last six months until the investor’s money ran out. But we had some great people: Roger Black was the art director, Terry McDonnell was an associate editor, and Barry Siegel, who later won a Pulitzer for the L.A. Times, was a reporter. It was a children’s crusade.

AP: And after that?

DS: I started freelancing and worked as a stringer for the New York Times. I started putting together magazine assignments and began to come into the orbit of Hollywood assignments. Then in 1975 I shot a story for the New York Times about the decline of the city of Hollywood, and it was published so disappointingly that I realized I was turning into a complete hack. I realized that if I wanted to do anything of interest I was going to have to self-assign and do more personal projects. So I began this work on Hollywood.

AP: You have a very particular take on Hollywood and filmmaking . . .

DS: I grew up in Los Angeles and my family has been connected with the movies for three generations. My great aunt was Gale Sondergaard, who won the first academy award for best supporting actress for the movie Anthony Adverse. Her husband was Herbert Biberman, a producer. My father was a television director and producer, and my mother worked as a publicist for Universal for a time. So I have this background. But my family was always also a little on the outside of the Hollywood world — they were left-wing intellectuals. My aunt Gale and her husband were blacklisted during the McCarthy era. We were more outsider-insider Hollywood people.

AP: That’s a pretty good description of your work.

DS: With my background, I probably started with a baseline that was different from the way most other photographers looked at Hollywood. Throughout the history of Hollywood, photography has been the happy handmaiden of the studio publicity machine, with the eager partnership of magazines and newspapers. There really hasn’t been much photography that has gone beyond that kind of standard celebrity-publicity photography. The very first time I was on a movie set, I wondered why all the other photographers were doing pictures that were so predictable.

AP: How does your work differ, would you say?

DS: I’m as amazed by the craft of filmmaking as anyone else, but I wanted to go beyond that. I’m interested in something that’s not on the surface, if I can possibly find it. My style is completely documentary — everything un-posed, candid, which is important, because when you’re dealing with Hollywood, you’re dealing with a high degree of artificiality. Recapitulating artificiality by posing actors and directors in imaginative ways doesn’t appeal to me.

AP: Has working for the web changed the way you shoot?

DS: Absolutely. When you shoot for print you are constrained, whether you even realize it or not, by the format. Magazines need a lead picture, they need a horizontal, and they have room for one or two pictures on the following pages, maybe. Then you might shoot a few extras if you think the subject will syndicate well. But with the web, you can run an infinite number of pictures, and you can shoot in many various ways.