Aaron Huey: Life on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

After six years struggling to photograph life on the Pine Ridge reservation, Aaron Huey now hopes he can help change it for the better.

In April 2005, Aaron Huey drove into Manderson, South Dakota, the roughest town on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, and started knocking on doors. “Hey wasichu (white boy), what are you doing with that camera?” yelled a young Lakota man covered in tattoos.

“Just looking for stories,” Huey answered. “You got any to tell?” Huey, then 29, was a determined if somewhat green photojournalist, riding a wave of positive attention from his recent photo project on a solo walk across America. Pine Ridge was the first stop on a self-assigned survey of poverty in America. The survey stopped there, but a new story had just begun.

Pine Ridge, the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, has been the poorest place in America for nearly 40 years, with 97 percent of its population living below the national poverty line in 2006. The infant mortality rate on the reservation is three times higher than the national average, the highest on the continent; life expectancy for men is 48 years old, roughly the same as in Afghanistan and Somalia.

The poverty and problems of Pine Ridge have been widely documented, yet Huey, who collaborates with publications including The National Geographic magazines, The New Yorker, and Harper’s, is one of the few journalists who has returned to “The Rez” again and again.

“For the first years I didn’t really know why I was returning,” Huey recalls. “I just knew that I couldn‚t turn away, that people were giving me something that I had a responsibility to share.”

After being welcomed so openly into the Pine Ridge community, Huey found he could no longer play the detached journalist. In March he launched a campaign on Emphas.is, an online fundraising platform for photojournalists, using posters by Shepard Fairey (of the Obama “Hope” poster fame) to bring awareness and aid the people of Pine Ridge. Although he has raised the $15,000 he originally asked for the project, he needs to raise at least $5,000 more by May 5 to create the billboards he feels will have the greatest impact..

The One Who Returns

His first trip to Pine Ridge, Huey mostly photographed the younger members of the tribe, many of whom are involved with gang violence and drugs. Young men like Travis Lone Hill, the tattooed teen who called him “wasichu,” immediately took him in and opened up in a way he’d never experienced before. The tribe’s elders, however, initially gave Huey the brush-off. They saw him as just another journalist preying on their misfortunes.

“I went in asking stupid questions about poverty and violence, I didn’t have enough background,” Huey remembers. “Like most journalists do when we go into a place for only a couple of days, we don’t really have the knowledge base to treat it right.”

His images ran with a story in Details magazine that, like many hastily reported stories, oversimplified the Pine Ridge situation and left a sour taste in his mouth. “Stories that skim the surface of statistics, only talking about gangs, poverty, and violence, don’t ever get around to the root causes,” Huey says. “That’s a common problem on short assignments, especially when you are trying to deal with centuries of painful history in just a few pages.”

Unlike most journalists who pass through Pine Ridge for a couple of days and never come back to hear how their work was received, Huey still gets complaints from friends there about that first story. “I’m also held responsible for what any writer writes,” he explains. “I’m the only one who returns.”

He’s worked to remedy the grievances. Over the years, Huey’s images have helped tell the story of the Pine Ridge Lakotas in_ The Fader_, Harper’s, and the New York Times‚ “Lens Blog”. Each piece digs a little deeper, helping a non-Native American audience understand the vast web of broken treaties and inhumane treatment that hobbles America’s indigenous people. But even when the stories are balanced and the photos are honest, people on “The Rez” accuse him of picking at their scabs. “Who gives you the right to tell our story?” they want to know.

Photo: Aaron Huey

It’s a pervasive question for any documentary photographer. And Huey doesn’t have an easy answer.

“From the very beginning when I came here I told you that I wanted to share the story of your life with the world, to be a witness to what’s happening here,” Huey reminded an elder who had adopted him into her family, when she asked him to remove his Pine Ridge images from the Internet. “You’re part of that, and I can’t take that back. It’s what I saw and it’s what people need to know.”

An Uneasy Fix

As his Pine Ridge project has developed, Huey‚s perception of his role in it has evolved. Although he takes care to avoid bias and judgement in his images, he’s begun to take more responsibility for the text accompanying his pictures. “As far as choosing a side, that has to happen through words,” Huey says. “My pictures paired with the wrong words are just as exploitative as the stories I condemn.”

In May 2010, Huey got up on stage at the University of Denver and unequivocally chose his side. In his 13-minute talk, which was posted to the TED lecture series online, Huey outlined 186 years of Lakota history, including dozens of broken treaties and the murder of unarmed women and children at Wounded Knee. After repeatedly holding back tears, he closed the talk by calling for the United States to honor its treaties and restore the Black Hills to the Lakota.

The speech touched a nerve, catching fire online, and suddenly thousands of people were turning to Huey and asking, “How can we help?” Huey is happy he’s called their attention to Pine Ridge, but as he says in his talk: “The suffering of indigenous people is not a simple problem to fix. The ‘fix’ may be much more difficult for the dominant society than, say, a $50 check, or a church trip to paint some graffiti-covered houses, or a suburban family donating a box of clothes they don’t even want anymore.”

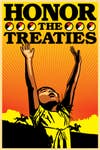

With the money he is working to raise through Emphas.is, Huey plans to produce posters and billboards based on his photos, working with Shepard Fairey and Ernesto Yerena (an activist and Fairey protege).

“I‚m doing the same things magazines are doing in raising awareness, I just hope to give it more depth and do it with brutal honesty,” Huey explains. “I’m going to be more blunt than mainstream media can be, using text written by Lakota non-profits that includes loaded language like Egenocide‚ and Eprisoner of war camps‚ to describe the reservation system.”

Huey also hopes to push people beyond indignation into action. All publicity materials will point to a Website that provides resources for researching indigenous issues and that will connect people to grassroots Native organizations.

“This is not a simple issue: I can’t just deliver a black and white story to the audience,” Huey says. “Ultimately my time at Pine Ridge produced a lot of very dark and intimate images, photos that show a world of suffering and neglect very few have been able to see. What people do with that new awareness of our legacy is up to them.”

Donations to the Pine Project end May 5. You can view Huey’s and many other worthy projects’ pages at Emphas.is. You can also check out more of Aaron’w work at AaronHuey.com.

Photo: Aaron Huey

Honor the Treaties

Honor the Treaties Poster

We Are Still Here

We Are Still Here Poster

We Belong to the Land

We Belong to the Land Poster

Lakota Tribe

Pine Ridge Playground

Pine Ridge Graffiti

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation