Nick Nichols Explores ‘The Last Place on Earth’

An extensive look at one of the most powerful collections of nature photography ever produced. Pictures by National Geographic's Michael 'Nick' Nichols, text by David Schonauer.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

For more than a decade, Michael “Nick” Nichols of National Geographic magazine has been photographing what no one had ever seen or will ever see again: a land where man has not been. In a remote corner of Central Africa, he and conservationist Michael Fay formed a unique partnership with the goal of discovering and documenting one of the world’s last undisturbed habitats, a place of “naive” gorillas and chimpanzees with no experience of man, of wide elephant trails leading to secret congregating areas, of leopards, dwarf crocodiles, vipers, and leeches, of a mythical ape known to Pygmies as kooloo-kamba, and a legendary Congo Basin dinosaur called mokele-mbembe.

Their efforts were capped with a trek like no other in history, a 456-day “walk” that covered some 2,000 miles across a checkerboard patch of untouched Africa, leading them to the Atlantic coast of Gabon, where Nichols photographed yet one more thing he’d never seen before: surfing hippos. Because of the men’s efforts, large sections of the area have been turned into national parks, offering this wild place protection from loggers, miners, and other symptoms of modern civilization. And yet, in an irony that does not escape Nichols, it was one of the hallmark acts of civilization, the creation of art, that allowed him to capture and bring this place back to all of us — to see it, to feel it, and know it as he did.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

The dense Central African jungle is dotted with bais — clearings made by elephants, where animals of all kinds come to socialize. One such place in the Odzala National Park, in northern Congo, is called Lokwe, and, according to Nichols, it is “gorilla Grand Central.” He camped at this place for 60 days in 2000, as Mike Fay and a team of Pygmies trekked toward the coast on their Megatransect. During that time Nichols observed what he believes were 365 different gorillas, a number that park officials thought too high until a recent study found some 500 individuals there. On his first day at Lokwe, Nichols sat on the ground, covered himself with a light camouflaged netting, and watched as this lone silverback appeared. The gorilla was challenging another male, in the oblique way of gorillas. Undercutting the tension of the moment, for Nichols if not for the gorilla, were colorful butterflies dancing around the frame. Nichols shot with a Canon EOS-3 and an EF 500mm f/4L USM telephoto, with an exposure of 1/1,000 second at f/5.6 on Kodak Ektachrome E100SW transparency film. “I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the best image I would make there for almost the entire time,” he says.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

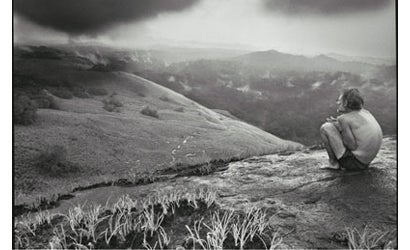

Nine months into the Megatransect, Nichols photographed Mike Fay atop a hill overlooking the vast expanse of undisturbed Africa through which the group was traveling. It was one of those rare occasions when the trekkers emerged from under the dense forest canopy and were able to see a horizon — an unsettling site for the Pygmies, who could then imagine how far from home they were. “A storm had just passed over, the light was beautiful, and Mike was sitting there, cold from the rain,” says Nichols. While walking with Fay’s group, Nichols put away his SLRs and color film and traveled only with a small front pack and a single Leica rangefinder with a 35mm lens and Tri-X film. “I wanted to be as unobtrusive as possible, to simply document what the group was doing and seeing,” he says. By this time, the relationship between Fay and Nichols had begun to change. “Mike was adapting to this place in a way that was personal for him,” says the photographer. “After I took this picture I went over to talk with him, but I almost felt like I was intruding.” In his Megatransect journals, Fay writes, “Living this way, walking all day, focused, naked, in a humanless world, was pure intoxication with complete clarity. Nothing was missing and yet life couldn’t have been simpler. Any intrusion became a noise so loud that it burst the eardrums.”

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

In the fading light of dusk, Nichols shot a genet he could barely see.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

Elephants digging for salt in Dzanga Bai, a remote clearing in the jungle of the Central African Republic, which Nichols shot in 1993.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

In the jungle, not all animals can be seen, especially those that travel and hunt by night. In 1993, Nichols began photographing the Ndoki Forest in northern Congo for a National Geographic project, using infrared camera traps as part of his photographic arsenal. The idea behind these devices is simple — an animal breaking an infrared beam triggers a camera shutter and remote strobes and thus “captures” itself on film. In reality the traps presented problems, says Nichols. “Batteries blew up, flashes melted, animals ate the cords. The devices were so sensitive that we got thousands of false hits and empty frames.” However, not all the animals got away. In one frame, made in the Ndoki at 1 a.m., a leopard triggered Nichols’s trap, which recorded the big cat’s passing just as it reached the edge of the frame. Ironically, the composition of the image was not dissimilar to the kinds that Nichols frames himself — compositions full of movement and tension. Since then, Nichols has perfected the camera-trap setup, but the images he makes all have a similar feeling. “With camera traps, I try to set the photos up so they’ll be like what I would actually take if I were sitting there,” he says.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

Congo, 1999: Traveling down the Motaba River, Nichols encountered a hunter who had just shot a mother mangabey for dinner. The animal’s infant would not leave the mother’s body. That evening, Nichols saw the terrified infant being played with by the children in the nearby village. “People see pictures like this and become outraged by the killing, but I’m always careful to point out that this man was simply getting food for his family,” says Nichols. “The African bushmeat trade, in which animals are slaughtered and used to feed cities far away, is a different issue entirely.”

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

A Bantu hunter in a Congo village with his shotgun and prey — a spot-nosed guenon.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

Nichols shot this male elephant bluff-charging his canoe in the Mambili River in Congo in 2000.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

During the Megatransetct, Nichols shot this young and frightened mandrill in a hunting camp in Gabon; its mother had been eaten.

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

Shooting in Congo in 1999, Nichols made this photo of Babenzele Pygmies gathering nuts, forest spinach, and mushrooms. “I have to be sensitive to the animals I photograph, but even more so with the indigenous culture,” he says. “I tend to end up among the wildest people on earth, and they’re just as afraid of me as animals are. They’re really put off by my presence, and the camera and flash.” His methods for photographing such peoples are both straightforward and calculated. “My motto is to make the experience fun for these people, so when I leave they won’t feel like this guy just came in and took all of their images and left.” Polite body language helps. “I’m much taller than most of the people I photograph,” he says, “so I sit down a lot.” He also trades his bigger Canon SLRs for a smaller, less intimidating Leica rangefinder. “It lets me be more unobtrusive,” says Nichols. “If a party starts and a big dance breaks out, I can use the Canons, because the situation is already fun. The flash going off becomes part of the magic of the ritual. But if we’re sitting around quietly, then the Leica is much better.”

© Michael Nichols / National Geographic

|| |—| | Related Links www.michaelnicknichols.com www.nationalgeographic.com | The Photographer

Being an expedition photographer for National Geographic means also being a supply sergeant and logistics officer. “You spend so much time planning and fund-raising for a project like the Megatransect that you can become overwhelmed,” says Nichols. For more than a year prior to the big trek, Nichols and Fay worked tirelessly to put together a vast array of photographic and camping gear, plus dried food full of chemical preservatives; they eventually filled some 80 crates that had to be shipped to one of the remotest areas on earth — gear including six Canon SLR bodies with lenses ranging in focal length from 17mm to 600mm, two Leica M6 bodies with 35mm lenses, and eight SLR bodies to be used in camera traps. Every detail of the trip had to be considered, including the power source for all the electronics the group would carry.

Lugging large batteries or generators would be out of the question, so everything was converted to run on AA batteries. Eveready donated Energizer batteries, but there was a mix-up in the order. “We asked them for a certain number of AA batteries, but they thought we were asking for that number of cases of batteries,” recalls Nichols. One day a truck pulled up outside of his Virginia home and $60,000 worth of AA batteries were unloaded. “I’m still using them,” he says.

Once in the field, however, it is not gear that guarantees success but patience. “What National Geographic offers me as a photographer is time it takes time to get the kinds of pictures I make,” says Nichols.

As a staff photographer at the magazine, he is a member of a rarified group. Most photographers who shoot for Geographic are on contract; only five, including Nichols, are on staff. For much of his career Nichols too was a freelancer and member of the Magnum photo agency, but he decided to go on the magazine’s staff in 1996 because “it was the best way to do the kinds of things I wanted to do and to get involved in projects that could really make a difference — like getting these national parks set up in Africa.”

In the 1980s, when Nichols was launching his career, he was known less for his environmentalist inclinations and more for his adventurous ones.

A 1987 article about Nichols in American Photographer magazine was sensationally titled “Nick Nichols in the Danger Zone” and featured a portrait of the then 35-year-old photographer lying bare-chested in a hammock grimacing at the camera while waving a machete through the air.

In those days, Nichols’s assignments took him into the eyes of hurricanes, onto icy cliffs in Alaska, and through the thundering rapids below Victoria Falls. French Photo magazine dubbed him “the Indiana Jones of photography.” Elizabeth Biondi, then photo editor of American Geo magazine (and now at the New Yorker) said of Nichols, “He is so daring. He went rafting, and the man did

not swim. He went to Venezuela and he had never been outside of America.”