Heroes of Photography: Phil Borges

Honoring the world's most courageous women.

Many photographers have documented the difficulties faced by Earth’s indigenous peoples, from poverty to prejudice, sexism to outright violence. Few have made as big a difference with their pictures as Phil Borges. Widely exhibited and published, Borges’s work has depended on close partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which provide the means to get the photographer to places that concern him. Yet the seed of Borges’s latest project was planted on a self-supported project to photograph shamanism around the world. (“There’s no NGO that’s out to protect shamans,” he jokes.) Here, American Photo’s Russell Hart recounts Borges’s journey.

Phil Borges was on his way to meet an Ecuadoran shaman in 1999 when he was introduced to Transito , a wizened nonegenarian living with her dog in an Andean village. This unlikely lady, it turned out, had almost single-handedly reformed the region’s exploitative, deeply entrenched plantation system. “When Transito was a little girl, most of the indigenous people were indentured servants on the haciendas,” Borges explains. “The owner of the hacienda where she worked was sexually abusing her, and when she was 17 she started to speak out about it.” She was jailed repeatedly for her defiance, and each time forcibly returned to the hacienda. But that experience turned Transito into an ardent advocate for her fellow workers, and she went on to lead protests against their mistreatment. One such action was a work stoppage. “The hacienda’s workers went on strike, and all of a sudden nobody had any food,” says Borges. “It let everybody know how important these people were to Ecuador’s economy.”

| Phil Borges Gallery****Heroes of Photography Main Article – Gallery The Other Photographers Brent Stirton – Gallery Chris Hondros – Gallery Fazal Sheikh – Gallery Hazel Thompson – Gallery John Dugdale – Gallery Joseph Rodriguez – Gallery Stanley Greene – Gallery Timothy Fadek – Gallery Yunghi Kim – Gallery |

Borges took Transito’s portrait, and he realized that the image would be the first in the next project he envisioned: a study of the global empowerment of women. “You can’t help but notice the egregious gender inequality in the developing world,” says Borges. “It occurs in every arena: education, division of household labor, political representation, access to credit and health care. And I thought, I’d like to do a series of portraits of women who’ve challenged that sexist status quo, and in the process improved the life of their communities.”

That project was put on hold by both the events of September 11, 2001 and the work required to realize another of Borges’ dreams, the creation of an organization he named Bridges to Understanding. Bridges pairs schoolchildren in developing nations (India, Kenya, Peru, and Nepal among them) with their peers in America, dispatching volunteers to give them the skills and tools (cameras included) needed to “tell stories” about their own cultures, as well as the computers and Internet connections to share them with one another. “I wanted to create a sort of laboratory for cross-cultural understanding,” says Borges. Bridges is now housed by Getty Images and supported with donations in kind from Canon, Adobe, and Microsoft, among other sponsors. It has a fully-developed curriculum based on the United Nations’ millennium development goals. (Visit bridgesweb.org.)

Despite its great success, the program took its toll on Borges as a photographer. “I just poured all my energy into it,” he says. “All I was doing was being an administrator and a fundraiser. I didn’t shoot for four years. I knew I had to start a photo project or else I’d go crazy.” The catalyst for that change was provided by a serendipitous call from CARE, the relief agency that gave the world the “care package,” to ask Borges if he would work with them. “I learned that CARE had really become a development agency, and that the cornerstone of its work is the empowerment of women,” he says. The agency’s new mission meshed perfectly with the unrealized project that Transito had inspired years before. Borges went on to photograph, on location in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Ghana, Guatemala, and other parts of the developing world, many of the indigenous women involved in the community improvement programs CARE had established. “The way CARE works is ingenious,” he says. “They don’t bring in outsiders to do this work. They hire locals.”

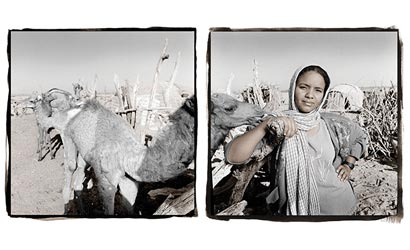

One of those locals was Abay, a young woman from Ethiopia’s Muslim Afar tribe. The Afar “circumcise” virtually all their girls by the time they are 12, a practice they believe to be ordained by Islam. Abay would have none of that, and fled her village at the age of 10 to live with a supportive godfather in the capital city of Addis Ababa.

“It was a completely heroic thing to do,” says Borges. “No one had ever refused.” Yet that was just the beginning of Abay’s heroism. Eight years later she returned to her tribal community as an outreach worker for CARE, helping to establish health posts and build clean-water wells — and taking it upon herself to campaign for the end of female genital cutting. Abay was routinely harassed by men of the tribe. “They accused her of being paid by CARE to come and destroy their culture,” says Borges. “But she told them that nowhere in the Koran is it written that girls must be circumcised.”

Abay finally convinced the women of the village, who always performed the ritual, to let her videotape it. And then she managed to show her footage to the all-male village elders, none of whom had ever witnessed the ritual themselves. “The men were so horrified that they voted 15 to two to end female genital cutting in their village,” says Borges. “Now they’re trying to spread the word to other Afar villages.” Yet this outcome was not the direct result of CARE’s initiative, Borges points out. “It’s less a story about ending female circumcision than it is about women getting a voice in the community,” he explains, adding that as a result Afar women now participate in village meetings. “All you have to do is give a woman a little education about her rights, and the resources to do something with them, and she can transform a community. It’s the best way to fight poverty and injustice.”

Borges’ subjects all have similarly powerful stories, from a Bangladeshi woman who created an organization to protect the rights of sex workers to the first female Afghan photojournalist. Those accounts are paired with their portraits in Women Empowered: Inspiring Change in the Emerging World (Rizzoli, $30). The project is “a deeply inspirational work,” writes Isabel Allende. “Phil Borges has brought us face to face with heroes — remote and mostly unknown women — bringing social and economic justice to women and girls worldwide.” The book’s companion exhibition, sponsored by HP, is printed on the company’s new Designjet Z3100 printers.

Though his new project is about other heroes, Borges is one of ours because he has the ability to find an uplifting angle on stories many other photographers tell in hopelessly grim detail. “I try to take something negative and put it in an inspirational wrapper,” he says. “That way, people pay more attention.”