Posting a copyright notice on social media doesn’t actually accomplish anything

What to know about the typo-laden privacy screed you may have seen going around Instagram.

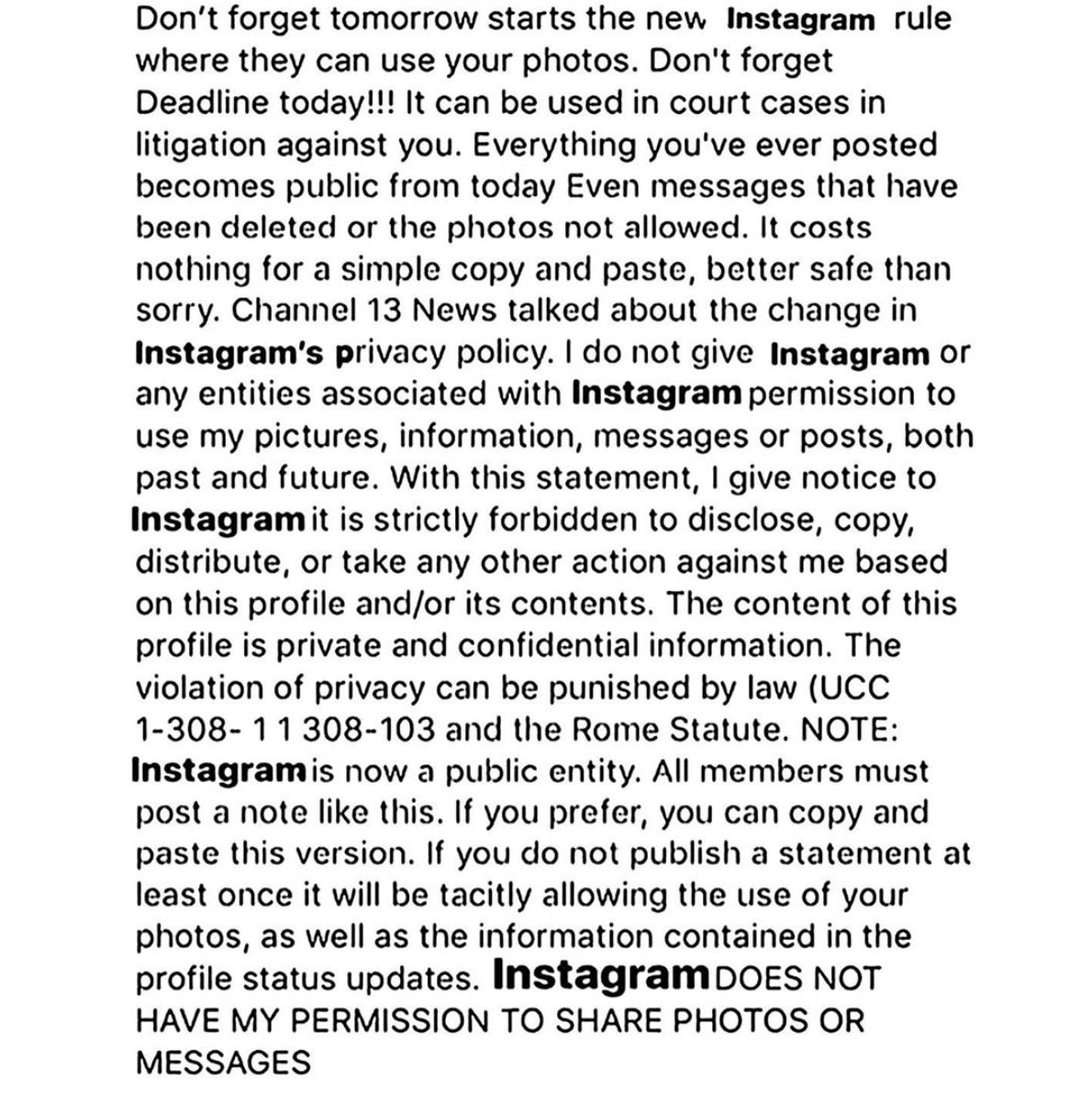

If you’ve logged into Instagram since last week, you may have seen people posting a long, typo-laden screed about a new rule going into effect that gives the company the ability to sell, use, or share your photos unless you repost a specific message denying it. I have even seen a few famous photographers doing it.

The statement sounds official, but it’s actually just the latest iteration of an internet chain letter that won’t do anything to protect your privacy or intellectual property from the social media networks or the wilds of the internet in general.

Various versions of the message exist, but they culminate with a declaration of “Instagram does not have my permission to share photos or messages.” Unfortunately, you can type this all you want—or run and shout it out loud at a semi-crowded Dave & Busters—and it still doesn’t change the fact that you have, in fact, given Instagram and other social media services the right to share your images and more.

Dig into the Instagram terms of service and you’ll find a section about permissions you give the company. These legal terms used to be even more complicated, but they got slightly simpler thanks to the European GDPR regulations, which require companies to clarify the actual cost of signing up for their services.

Under the Permissions topic, you’ll find the following phrase: ”We do not claim ownership of your content, but you grant us a license to use it.” Simply put, this means that Instagram doesn’t require you to turn over the intellectual property of your photos and videos to them completely—you still own that media and can sell it or sign it over to someone else if you want.

The terms go on to explain the license you’re granting the company. Here’s the more complicated section. “…You hereby grant to us a non-exclusive, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works of your content (consistent with your privacy and application settings).”

If you’ve spent any amount of time examining the terms of service for social media networks or even photo contests held online, these phrases probably sound familiar. You’ll find very similar terms on Facebook and Twitter as well.

Back in 2012, two of those terms showed up in the Instagram agreement after Facebook purchased it: “transferable,” and “sub-licensable.” It caused an outcry. The concern was that this gave the company the ability to basically sell user photos as if they were stock images, which wasn’t technically the case and it certainly hasn’t panned out that way.

If you’re particularly worried about your images ending up in advertisements for brands, the terms lack some essential permissions. The primary roadblock there is that it’s not a commercial license, which is typically required in an advertising situation. And chances are you don’t have signed photo release contracts for the people in your photos, or property releases for recognizable landmarks, both of which advertisers typically require.

Interestingly, however, Instagram and Facebook does have a little leeway when it comes to using your name or likeness as they relate to sponsored content. For example, you may have seen sponsored Facebook posts above which you’ll find a list of other friends that have liked that content or the brand sponsoring it. In that case, Facebook and Instagram have the right to display your name and even your profile picture next to the sponsored content you liked. It’s complicated, but the system has been in place for years without much backlash.

As for Instagram sharing your private messages, the company specifically says it can share your content, “consistent with your privacy and application settings,” which means it will keep private stuff private, at least to the best of its ability. That’s not to say that someone couldn’t get access to it, however, through a hack or a data breach. If that’s something you’re very worried about, you could consider a service like WhatsApp, which is also owned by Facebook, but encrypts your messages so they’re mostly useless to a hacker.

If you’re really concerned about protecting your photo and video copyright, there is an official process through which you can submit your works on Copyright.gov. It’s a somewhat tedious process, but it will give you stronger legal ground on which to stand if someone infringes your photos or videos.

If you’re still not comfortable with the terms, you can terminate Instagram’s licenses to your images by deleting the content—though that’s not the case with every social media network. So, if you’re really concerned about companies using your images, you may have to suck it up and actually read those terms you typically skip during sign-up.