Walker Evans’ American Photographs, and five other photobooks worth checking out

Get inspired with these six fantastic photobooks, including Steven Shore's memoir and Zora J Murff's exploration of Blackness in America.

This month, we look at a wide range of photobooks. Mika Horie’s cyanotypes present the world in blue; Stephen Shore’s memoir looks back on his long career; Zora J Murff explores Blackness in America; Stephen Gill’s photos of birds on a pillar present a new take on wildlife photography; a presentation of 3D images from the dawn of photography hints at what might have been; and Walker Evans’ classic photos of Americans in the depression remain timely.

Mika Horie, Trees, Water and light — 120 pages, softcover (IBASHO & the(M) éditions)

Cyanotypes are one of the oldest photographic techniques. Using iron salts, these prints are exposed from ultraviolet light rays and develop very slowly. Light and shadow are displayed in gradations of monochromatic blues. Photographer Mika Horie’s book is constructed from Japanese paper she has made by hand, and, with an original print on the cover, each copy of the book is different.

Horie says, “Blue has the effect of escaping from time and material possessions that float past, present and future. I believe this is the only color that allows you to escape from yourself and enter your world of poetry and the memories deep down in your heart.” The monochromatic blue cyanotypes suggest rather than show; printed on handmade, rough-hewn paper, the photos take on a hazy earthiness, one of speculation rather than firmly fixed images.

Read how Horie makes her paper.

Stephen Shore, Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography — 224 pages, hardcover (Mack)

While Modern Instances contains photos, it isn’t exactly a photobook. It is a memoir, a collection of reflections and interviews, and a look back on Stephen Shore’s long career as a photographer. Shore is well known for his images of everyday objects and banal scenes, and in this book, he discusses his influences, his experiences, and what photography means to him.

Shore says, “One of the reasons I have been drawn to photographing everyday life is because the everyday world is fertile ground for communicating the experience of living with attention. A dramatic event acts upon you. To attend to the quotidian requires you to act.” In this book, he explains how he sees the world, and we can learn from him to see the world with fresh eyes.

Zora J Murff, True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) — 256 pages, softcover (Aperture)

True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) is “a chronicle of survival,” which combines Murff’s photos with found and appropriated images, and a number of texts commissioned for the book. Described as “a manual for coming to terms with the historical and contemporary realities of America’s divisive structures of privilege and caste,” this book catalogs the Black experience and juxtaposes contemporary images with historical photos, advertisements, and more.

Murff asks, “What does it mean to be engaged in this act of photograph that has been used to denigrate me?” A former social worker, he brings his experience working with juveniles on probation to this exploration of Blackness in America.

Check out the PDF playlist for the book.

Stephen Gill, The Pillar — 224 pages, hardcover (Nobody Books)

Sometimes the most arresting photobooks are based on very simple premises. Stephen Gill set up a camera looking at a pillar, which was next to a stream in a flat, open landscape in Sweden, near his home. You see the open fields, houses in the distance, and the subtle vanishing point of the stream. The seasons change, the weather comes and goes, and the light varies. All the while, birds come to perch on the pillar.

Gill says, “The pillar had funneled the birds from the sky offering them a place to rest, feed, nurse their young, and look around. I was captivated. The images were often chaotic, the birds offbeat and awkward like contortionists, but the shapes and soft lines made by their bodies and wings were arresting.”

The pillar attracted many different kinds of birds: sparrows, eagles, owls, egrets, and more. These aren’t just bird photographs, not the type of images you see on calendars or postcards, but birds caught still or in half-flight with a camera triggered by a motion sensor. The Pillar, now back in print, is filled with these chance moments caught by the camera, which look much more alive and dynamic than most bird photographs. These photos are about the changing landscape and the creatures that live in it as they come and go, sharing our world.

Denis Pellerin and Brian May, STEREOSCOPY – The Dawn of 3-D — 216 pages, hardcover (London Stereoscopic Company)

In the early days of photography, two types of images battled for supremacy: flat images and stereoscopic 3D images. The latter used a sort of porto-virtual reality goggle (the stereoscope) that held two slightly different photos (the stereogram) together. These give the viewer the illusion of depth. First theorized by Charles Wheatstone in 1832, before the dawn of photography, the stereoscope became popular when David Brewster invented a portable viewer in the 1840s. In the following decades, these devices helped to popularize photography, though their use faded over time.

This book, written by art historians Denis Pellerin and Brian May, explains the process and technology behind 3-D photos. It also presents photos from May’s collection. The book comes with an OWL stereoscope, designed by May, who also has a PhD in astrophysics, to view some of the 150 stereoscopic images it contains.

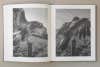

Walker Evans, American Photographs — 208 pages, hardcover (Museum of Modern Art)

First published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 to coincide with one of the museum’s earliest photo exhibitions, Walker Evans’ American Photographs is a classic of its time. In the forward to the second edition of the book, published in 1962, Monroe Wheeler, the museum’s Director of Publications, wrote: “It revealed a new master of the camera who expressed the tragic sense and troubled conscience of that period of economic depression and political change, although in mood and style it was reflective rather than tendentious.”

These photos—portraits, street photography, photos of houses and towns—show America during the depression, and many of them became symbolic of that era. Over the years, as America has moved on from this difficult period, these photos bear witness to the starkness of the times. The juxtaposition of photos showing the homeless sleeping in front of buildings with photos of couples on a day out at Coney Island highlight the disparities Americans faced, some of which have not changed since then.