An Homage to Gordon Parks

His death at age 93 marked the passing of a creative spirit of almost incomprehensible scope. Here, one of the many photographers he inspired looks at the work and world he left behind.

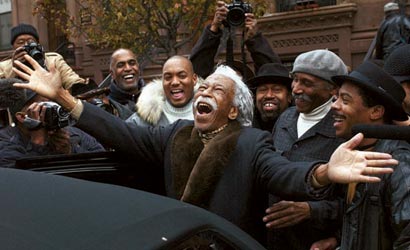

As the six pallbearers hoisted the dark brown wooden casket onto their shoulders, the voice of the occupant echoed off the walls of the sanctuary at the Riverside Church in Harlem:

“This is no farewell, but a gathering of those to act and make the crying of others much easier to bear.” Thanks to a documentary projected at the front of the church, Gordon Parks spoke the last word at his own funeral, giving comfort to those who had come to bid him good-bye as he went to join his long-departed parents, Sarah and Jackson Parks, and the son who shared his name.

The life of a child that began in the poverty of a clapboard house on the Kansas prairie ended in the opulence of a high-rise apartment opposite the United Nations. The pews of the church at his funeral sparkled with the likes of Gloria Vanderbilt and Lenny Kravitz. Smiling, while wiping away tears, I thought back to a time a few years earlier when I spent an evening with him in his 10th-floor apartment at the United Nations Plaza, a thousand miles and nearly a hundred years from his humble beginnings in Fort Scott, Kansas. On that night he told me about a life that began with a prophecy that was kick-started when a quick-thinking doctor plunged his stillborn body into a pan of ice water. “I started screaming and I haven’t stopped,” he recalled, laughing joyously.

Gordon Parks was a work in progress until the day he died, a dapper mass of creative energy, adrift in a boundless universe of his own creation. His was a restless spirit, guided by instincts and the ever present voice of his mother telling him that he could “do anything as well as a white boy.”

“And if you can’t,” she had said, “don’t come home.”

He was unique among that generation of post-depression era photographers at Life magazine who documented America’s emergence from the shadows of social disparity and racial disharmony to its ascendancy as a military and economic giant. From the beginning, he was one of the “others” who often were the subjects of Life’s photographers. His success in bridging the two worlds eventually made him a “stranger in one and social oddity in another.”

Today, with Oprah more powerful than Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham in her heyday, and Time Warner, the parent company of Life magazine, headed by an African-American, it’s difficult to imagine the America in which Parks grew up. It was a country where lynching in the South was

as common as church socials, and often celebrated with the same festive spirit. Meanwhile, in the North, whites lived a life of self-serving denial. Parks’s arrival on the scene was not universally celebrated on either side of the color line. But his presence was something that could not be denied, and, in time, it helped change the way that white America looked at blacks and how blacks looked at themselves. His marquee successes paved the way for those who followed.

Gordon Parks was born November 30, 1912, the last of 15 children. When his mother, Sarah Parks, died after his 15th birthday, the family that had nurtured him lost its core. Young Gordon was sent to live in Minnesota with an older sister and her husband, who, for some reason, disliked him instantly. By the time Parks was 16, he was out on the street, riding the bus between St. Paul and Minneapolis to escape the frigid nights. His first real job was playing a piano in a brothel.

His formal education was over by the time he was 17. For the next twelve years he worked at a series of odd jobs that barely earned him enough to feed himself and provide some kind of shelter. The jobs included playing with a professional basketball team, washing dishes in a restaurant, and bussing tables at Minneapolis’s Lowry Hotel, from which the Mutual radio network broadcast the sounds of the big bands of the day.

One of the band leaders, Larry Duncan, walked into the empty dining room, where Parks sat at the piano, playing a tune he had composed. Duncan was taken with the beauty of the composition and asked Parks what it was called. “‘Lost Love,’ and I wrote it,” replied Parks. Over the objections of his father and at his mother’s insistence, Parks had started taking piano lessons when he was six and had continued until his mother died. They were starting to pay off.

Parks played by ear, so Duncan had his arranger put the composition on sheet music, and it was played over the next Mutual broadcast. For a moment, Parks enjoyed instant celebrity and had the “questionable” honor of being the first black musician to play with a noted white orchestra, introducing their theme song on piano before they went on. His career as a musician was short-lived, however.

After gigs in Minneapolis and Kansas City, the band hit the road on a bus for New York. Duncan skipped out on the band when it reached the Big Apple, and Parks was stranded. After a few months of living hand to mouth, he turned to the depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, which provided plentiful meals and backbreaking work. Under the false illusion of security, he hopped a train to Minnesota and married his girlfriend, Sally Alvis. They moved to Philadelphia and lived there until the Conservation Corps job ended. Before long, they were back home with Sally’s parents. Parks found a job waiting tables at St. Paul’s Minnesota Club. His hard work brought him to the attention of one of the club’s members, James Hill, president of Northern Pacific Railway. He suggested that Parks interview for a job with his company. Parks was soon making regular runs on the North Coast Limited between St. Paul, Chicago, and Seattle. On these runs, he collected magazines left behind by the passengers.

The pictures by Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Carl Mydans, and other documentary photographers fascinated him. One day during a stopover in Seattle, he walked into a pawnshop and inquired about a camera in the window. The store’s owner wanted $12.50 for the 35mm Voigtländer, but he accepted the $7.50 that Parks had to offer and threw in a couple rolls of film. Another customer showed Parks how to load it. When he got the film developed back in Minneapolis, the clerk at the Eastman Kodak store was so impressed that he offered to give Parks an exhibition.

After studying the fashion pictures he saw in a copy of Vogue left behind by a train passenger, Parks got up the nerve to walk into an exclusive women’s store and ask if he could shoot fashion photos for them. After agreeing on the number of models and outfits, he was out the door to borrow a Speed Graphic camera from a friend and get a quick course on how to operate it. He returned to the store the next evening, ready to work. The confidence and poise he displayed impressed the owners, but in the lab disaster struck. All but one picture was double exposed, so he made a large print of that image and placed it on an easel at the entrance to the store so the owners could see it. They asked to see the others. Parks explained what had happened, adding that the others were better than the one he’d printed.

He was allowed to reshoot the images, and his career was launched. Marva Louis, the wife of the heavyweight champion Joe Louis, saw his work at the store and suggested that he move to Chicago, where she would help him get more work. With a new baby, the Parks family moved to Chicago. Once there, Parks started to shoot documentary work in earnest, focusing on the city’s ghettos. That work earned him a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, which brought with it the chance to do an internship in Washington, D.C., with the Farm Security Administration under Roy Stryker. The agency was already renowned for documenting poverty during the depression and launching the careers of the best photojournalists of the day. On his first day in Washington, Parks made a photograph of Mrs. Ella Watson, a black woman who had mopped floors for the government nearly all her life, posed with a mop in front of an American flag. He called it “American Gothic.”

During World War II, Stryker brought Parks to work for him at the Office of War Information as a correspondent. He joined the staff of Life magazine in 1949, after working for both Vogue and Glamour. His successful foray into fashion photography, just as he was cutting his teeth on documentary work, made him an instant celebrity in a world in which he was a total stranger. That he excelled in both is a testament to his genius. Parks inspired a generation of photographers, both black and white. It wasn’t just his work but also his determination and desire to reinvent himself that captured the imagination of so many. He never grew tired of pushing the envelope. For me, he demonstrated that respecting his subjects was the first step toward winning their confidence. Whenever possible, he became a part of the subject’s environment: “I never showed up with a camera and started shooting. I wanted people to get to know me as a person,” he said.

In Brazil to work on a story about poverty, he slept on the floor of a favela to document the life of an asthmatic boy named Flavio da Silva, going to a hotel once a week to change clothes and shower. His essay on Flavio brought in thousands of dollars, enabling Parks to bring the boy to the United States for treatment.

In 1956, when he and journalist Sam Yette were sent to Alabama to document the impact of segregation on the Causey family, they slept on a front porch. When he was sent to Italy to photograph Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini, he took care not to invade the couple’s privacy. All the world wanted to see a picture as proof of their controversial affair, and the couple usually took care not to be seen together. One day, however, when they forgot they were not alone, they embraced in the middle of the movie set. Parks, camera in hand, elected not to take the picture. “The golden moment was undeserving of betrayal,” he said. Bergman and Rossellini were aware of his courtesy. The next morning, they invited him to bring his camera while they took a stroll together along the beach.

I was seven years old when Gordon Parks joined the staff of Life, and 12 when I got my own first camera. By that time, Parks had already discovered the wonders of Paris and beyond. At that point, my world didn’t extend much farther than a few blocks beyond our front door on Baldwin Street on the east side of Detroit. The day I looked in the mirror and saw Gordon Parks looking back at me, I knew that anything was possible. I followed in his footsteps to France, Germany, and beyond as a staff photographer for Newsweek. Growing up, I’d thought that the only way a black man got to any of those places was by donning a uniform and becoming a soldier, as my father had done. Parks changed all that for me. He allowed me to explore the world on my own terms.

I cannot imagine that there is one black photographer, male or female, of my generation or later who doesn’t feel the same way about Gordon. They may have developed a different sensibility about photography, but not about the man. Thanks to him, we’re no longer an oddity in our own minds or in the eyes of the world. “Gordon Parks was like Rosa Parks,” says the renowned jazz photographer Chuck Stewart. “A lot of us wanted to sit down, but she did it. There were black photographers before him, but he walked through the front door and did something.”