Scientists are scrambling to take more photos of this seemingly alien comet

The object is the second we've observed that has origins in another solar system.

Astronomers have snapped a shot of what could be a comet visiting us from another solar system—only the second interstellar object we’ve ever spotted in our own cosmic neighborhood. The fact that it showed up so hot on the tail of ‘Oumuamua, an infamous (and still largely mysterious) cigar-shaped rock first seen in late 2017, suggests these alien interlopers might actually be pretty common.

‘Oumuamua only made a brief visit, but has periodically popped back into the news as researchers puzzle over their scant available data to determine its make-up and origins. The newer object, dubbed C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), should prove easier to investigate. Borisov will continue to approach the sun until early December before it starts the outbound leg of its journey. That gives us plenty of time to keep gathering data.

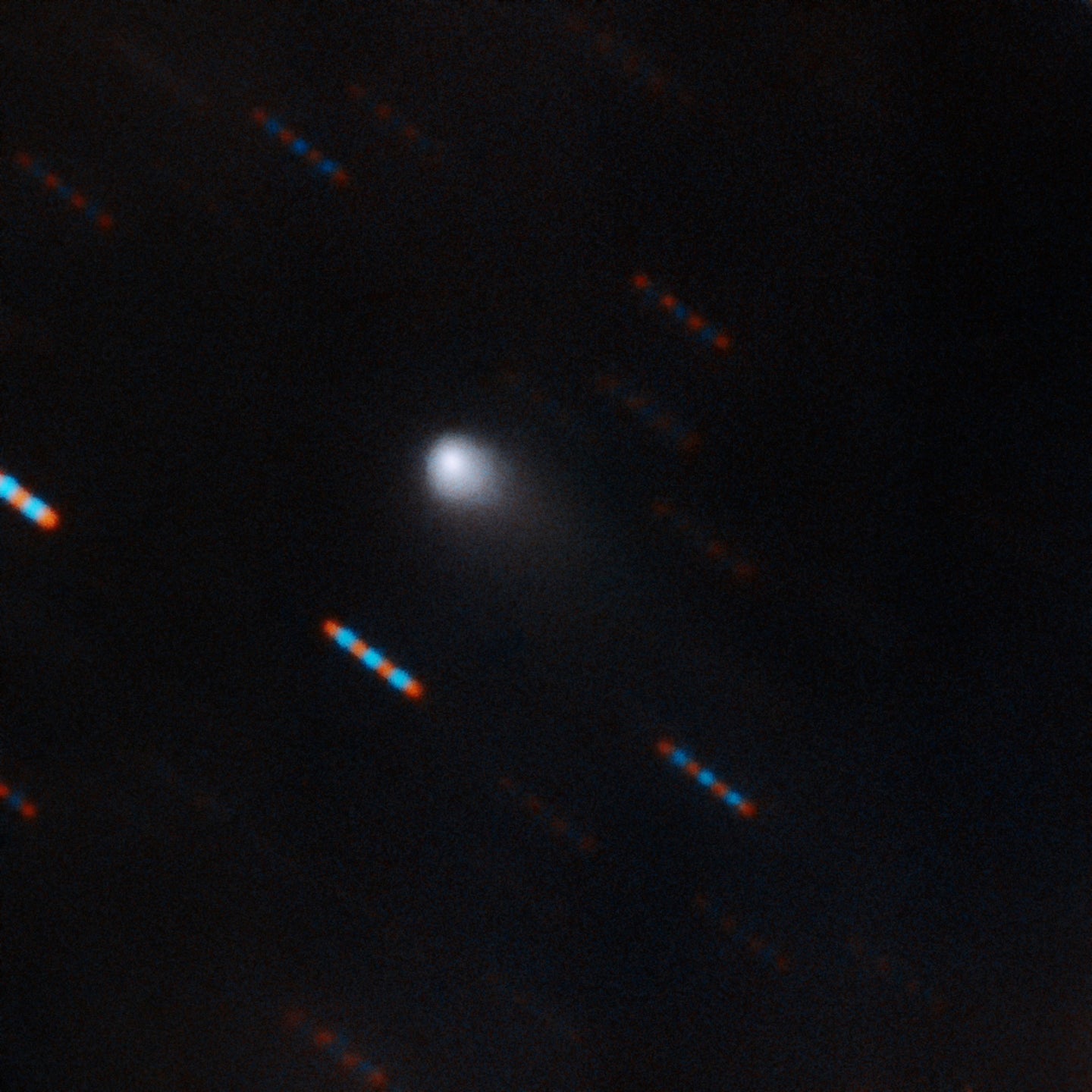

First spotted by astronomer Gennady Borisov at the MARGO observatory in Nauchnij, Crimea on August 30th, C/2019 Q4 showed itself off in more detail last week. Using the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph instrument at the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii, researchers captured a colorful glimpse that revealed a well-defined comma and tail—signs the object is very likely a comet. Like comets in our own solar system, C/2019 Q4’s spectral signature suggests it’s a “dirty snowball,” made up of ice and dust. But there’s something distinctly alien about this familiar object: its speed.

“The comet’s current velocity is high, about 93,000 mph, which is well above the typical velocities of objects orbiting the Sun at that distance,” Davide Farnocchia of NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies said in a statement. “The high velocity indicates not only that the object likely originated from outside our solar system, but also that it will leave and head back to interstellar space.”

Scientists should be able to spot Borisov for a few more months, so they’re scrambling to collect as much data as possible during that time. For now, the supposedly-interstellar, possibly-cometary object dangles the intriguing possibility that other star systems might form dirty snowballs quite like the ones we have at home—and that they might drop in to say hello more often than we thought.