Zoe Leonard’s Epic “Analogue” Exhibit Changes The Way We See Consumer Culture

An eleven-year exploration of the pre-Instagram cityscape on view in a dizzying set of grids

While Zoe Leonard may be revered for her feminist, queer rights, and AIDS awareness activism in her early work (as founding member of the artist collectives fierce pussy and GANG), she has also long been attracted to the ways in which images can be classified and ordered to play with the viewer’s experience of seeing.

Upon first entering “Zoe Leonard: Analogue,” on view through Aug, 30, 2015 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it takes a moment to adjust one’s eyes to the sight of square images set in grids lining the three walls of the Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium. It is immediately obvious that the artist has departed from her overtly activist role to show the changing urban landscape in a more subtle form. There’s a familiarity in her stark images taken head-on of the decaying and shuttered facades of mom-and-pop shops lining the streets of New York—even as the once-ubiquitous barbershops, pharmacies, and discount goods stores of Manhattan are increasingly relegated to the fringes of the five boroughs.

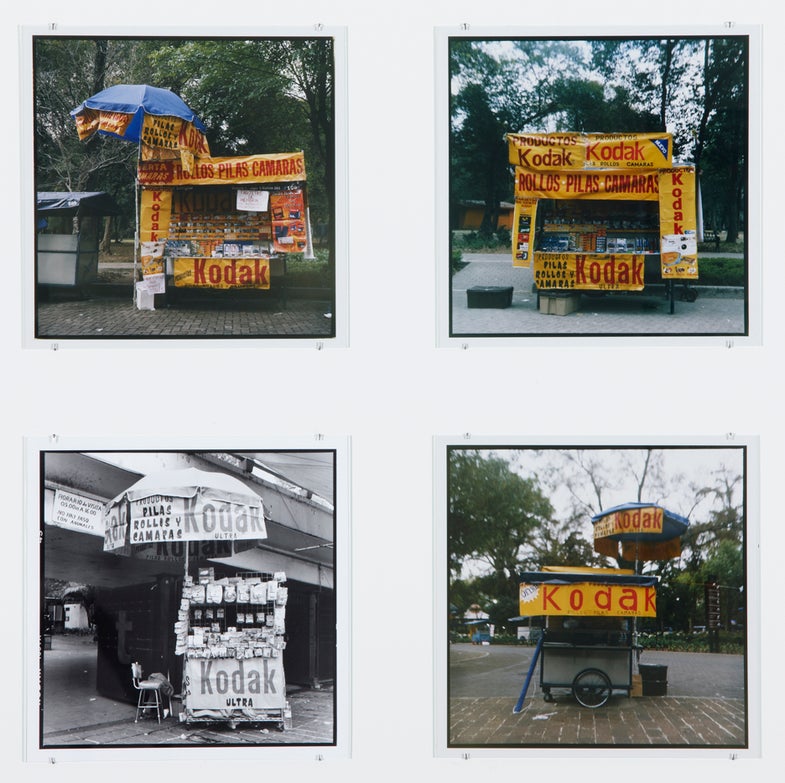

As Leonard began noticing these outposts disappear from our landscape, she began to follow merchandise circulation to Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America. She went to some of the places where the goods originated and then were later returned to be recycled and resold to witness the global cycle of production. What she found were goods and storefronts in Spanish-speaking countries, for example, that bear an uncanny resemblance to their American counterparts.

After spending time in the wilds of Alaska in the mid-90s, the artist—whose work has been shown in such prestigious exhibitions as “Documenta IX,” “Documenta XII,” and three Whitney Biennials—became increasingly aware of the strain material production puts on the environment, as well as the ways in which such energy and devotion is put into selling and consuming products. “Analogue” is the result of 11 years (from 1998 to 2009) using her Rolleiflex camera to document the independently owned storefronts closing throughout the city she’s called home for most of her adult life. Here, the textiles, cardboard, clothes, kitschy signage, and iconic logos represent the shifting vernacular of cities and a semblance of a crumbling American Dream.

“Analogue” is as much about planned obsolescence as it is the changing nature of the cityscape through the process of gentrification. What is most striking, however, is the absence of humans and the natural environment in these images, which are the implicit victims of mass production.

Categorized in 25 “Chapters” per the artist’s installation instructions, the serialized grids are also reminiscent of the image streams dominating computer screens and smart phones today. And that’s where the presentation of the work, six years after its completion, takes on an interesting twist in context: though the series completely predates the 2010 launch of Instagram, and is shot and printed using analogue processes, it echoes the square format and film-like filters of the images bombarding social media today. The 412 photographs are a dizzying display that, like Taryn Simon’s categorized works in a 2012 MoMA show, document a complex system in society that isn’t easy to decipher.

Leonard’s final “Analogue” chapter is a compendium of photographs the artist took in Poland of objects shot overhead in what appears to be a flea market. The way the objects are displayed on the ground, and in effect catalogued, in this very categorized series, is a meta view of the outcome of the world’s dependence on material. The trail of goods continues seemingly into infinity.