Tina Barney, Inadvertent Photographer of the Rich, Dissects The Concept of Value

“I was horrified when I realized people weren't seeing what I saw in the pictures”

You never start out suspecting your work will be of value. It’s funny, but most of the people in my pictures don’t buy my pictures. I think it’s too close to home for them, but that’s removed from what I think my pictures are about. The price of a photo itself, and the prices people are willing to pay for them, is really a question of value and priorities.

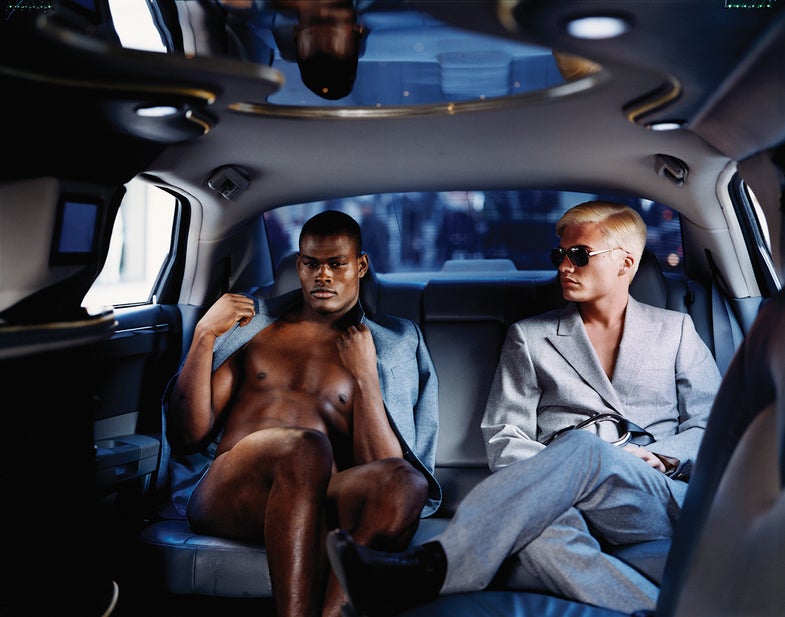

Figuring out the value of something is like calculating a formula based on making comparisons. I find that fascinating. Someone that owns a luxury car might know that a photograph costs $70,000, but what they don’t understand as intensely is how it’s made and how difficult it is to produce. That car is a functional, tangible object—a commodity or a status symbol, but it doesn’t have that heartbeat, that passion you have in a work of art, and maybe that’s not a priority for some people. I don’t mean to be critical, but I think unless someone has been a collector for a very long time they don’t really understand the time and the energy and the knowledge it takes to make art—the agony and the ecstasy of it all.

There’s a huge public that loves and really appreciates photography, but when they see your work is being sold for $70,000 they’re not thinking about the hours of setup and 10 bags of equipment it takes to make that photograph. They’re thinking about the 60th of a second it takes to click the camera and crank it out—not the years of working in the studio and paying for supplies and trashing bad prints, and the fact that you have to make enough money to keep making your work. It’s important (and of course it’s nice) to sell something at a gallery or at an auction, because it keeps the circulation going. It keeps the blood moving. What you learn from your work being in circulation like that is really important. You have to see it out there and in context to know where it stands. It’s like talking to yourself otherwise.

I was horrified when I realized people weren’t seeing what I saw in the pictures, but it was naive of me to think they would. It was a slap in the face, but I was young, I was probably only about 29, and it didn’t last long. The drive to make the work was stronger than the fear of being criticized. I wanted people to talk about the photographs themselves, the composition, the structure, the scale, the color. That’s what I’m interested in—relationships, people, the way they move and the way they walk, the way a room is set up. The sociological. It’s like I have blinders on—I see the formal parts of putting a picture together, paired with the human figure, and human emotions.

I honestly never even thought of the fact that I was photographing the upper class. Critics put that label on things, and had the revelation that I was documenting the upper class from the inside. I was photographing my family and friends, but it doesn’t feel documentary to me, though it is playing with that style. The fact that the people I was photographing were of a certain class or background wasn’t important. It was familiar. It’s home. It’s speaking in my own language.

Tina Barney’s career-spanning solo show, “Four Decades,” will be on view at Paul Kasmin Gallery through June 20, 2015