Thomas Struth on Documenting Invisible Systems

"I’m interested in trying to open some doors and see into what we’re doing."

Great

Though many artists seek to draw parallels among humans, the natural environment, and technology, few get quite the insider’s view or present it in such a large scale as Berlin-based photographer Thomas Struth. In an attempt to open doors to the “invisible” systems upon which modern existence relies, the artist takes us inside robotics labs, Internet servers, and other technological spaces to show us how these complex manufactured landscapes are tied to human and natural existence in Nature & Politics.

The series is on display now as part of the inaugural programming at the Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University in Houston, Texas, which opened to the public on February 24 and calls itself an institution designed for “creating collaborative works of all kinds and presenting innovative, transdisciplinary experience.”

When we spoke to Struth he was preparing to address the Moody in a panel discussion along with Douglas Terrier, NASA Chief Technologist, and James Tour, the T.T. and W.F. Chao Professor of Chemistry and Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering and of Computer Science at Rice, both of whom work in the environments he photographs. Struth says that he was excited to talk about his work in the context of the Moody Center and the institution’s “open concept,” which he’s rarely encountered in a museum.

We spoke with him about how this work came to be and why it has an important place in contemporary politics.

Seestück

How do you think this work fits into the vision for the new Moody Center for the Arts?

The exhibition,Nature and Politics, comprises a body of 37 pictures. For the Moody, we’re not showing the photos that were made at Disneyland in Anaheim, which show a twist of reality between what’s real and what’s of the imagination. They were four very large pictures and there wasn’t enough room. I thought it would be interesting to show the works about technology exclusively.

Gregory Harris, curator of the High Museum, said of this series that your photographs of advanced technology evolved out of your photographs of jungles. Can you explain what he might have meant by this?

I think that’s a slight misinterpretation. I think I mentioned that, starting in the mid ’90s or so, when I traveled a lot in China, in some of my street pictures I started to become interested in multilayered subject matter. I was photographing very complex scenes and I was starting to look for bigger challenges. Photographing jungles came mostly from the desire to photograph something very complex that you wouldn’t be able to fully comprehend or fully read—and then I thought, okay, what subject matter might be fitting to use for this creation of such pictures? I thought about construction sites with scaffolding but that wasn’t so attractive because it related to too many different subjects. And then I thought forests would be good, but the forests in Germany would largely be pine trees with a lot of verticality. So I thought the jungle would be better, but it didn’t necessarily have to do with my interest in jungle structures. I had a lot of training in determining compositions of complicated structures (over a period of 12 years) and that helped me make decisions in photographing complex technological structures. But that’s a much different thing [than what he said].

Measuring

So what was the reason for it?

The main incentive for me to start to look at technology was really along socio-political or anthropological lines. The contemporary world seeks to entangle itself with the fascination and promises of technology, and progressively invests less interest and commitment to the humanities. And then we begin to shift more of what we’re doing and what influences our lives to the invisible. Like, we’re using the phone over FaceTime, but few people who have used phones over the Internet have ever been to a server farm. The Internet by and large is invisible. I’m interested in trying to open some doors and see into what we’re doing and use my ability as an artist and one who is highly trained in the translation of the real world into condensed pictorial metaphors and emblematic representations of a kernel of a particular phenomenon through photographs.

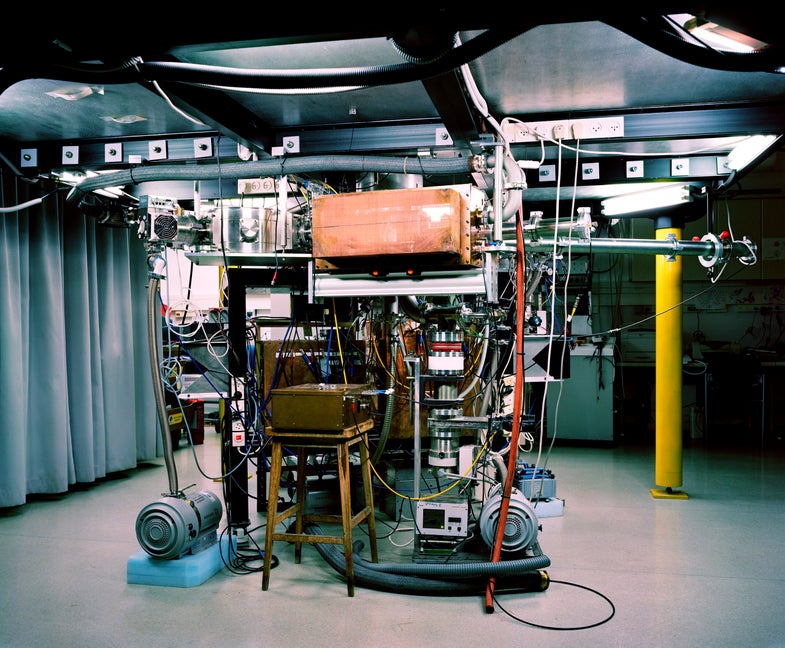

High Harmonic Generator Spectrometer

That’s quite a gift to us as viewers of your work, because like you said, we don’t have access to these systems we’re so entrenched in everyday. I’m wondering how that which we can’t see, including international politics, is entangled in the work you’re making?

I was born in 1954 and I’m German—I was obviously born after the war but there’s still a certain inevitable responsibility and political awareness. But in my lifetime I’ve never been as worried about what’s going on as I’ve been in the last few years. Certainly with Brexit and Trump being elected the situation is even more intense. There’s also a strange contradiction in this country: America believes it’s dominant in everything—including the Internet and social media (or should I say asocial media?)—but this creates unique worries and the loss of the work environment that people were used to. It’s a bizarre dynamic of having a president like that now—someone I see as a pathological narcissist. It’s scary.

Do you see politics changing the way you might make work going forward?

It could very well change it. It certainly will have a kind of influence. I’m developing something new which I’ll show in New York in November. The way I work has much to do with identifying the reasons for why I should work. And from then on, it’s about what kind of pictorial imagination it creates, and in what ways that might be connected to my reasons for working.

Z-Pinch Plasma Lab

Throughout the years of photographing complicated manmade structures, natural landscapes, and humans, have you found that there is commonality among these subjects? Or is there a common thread in the way you’ve developed a visual language for portraying these different things?

Yeah, I believe that with the distance that I now have from the bodies of work I’ve been making, I see that it represents different chapters of life. I see the city as an expression of the unconscious side of our existence. Cities are the results of decision-making, and all of the decision-making was made by humans and all of the unconscious impulses of what they like and what they don’t like and how they act and who they are—their personality and character. And so I became interested in the family and the inevitable gift you get when you’re born and the location and time in which you are born. The way I make a family picture in a half-composed setup is an acknowledgment of that idea. I don’t direct people. I just choose a frame and they can choose their place within it.

The pictures of technology have to do with the mindset of entanglement and passions and failures—which are human phenomenons. When someone gets obsessed with something [technological], he can’t look at himself with perspective. There are a lot of human questions in the work.

Most of these projects I started out of curiosity and I felt attracted to them, but then it became about what I just described. I started when I was 15 or 16, and it was then that I started to ask questions about who I was, who my parents were, and what was going on with the city I lived in. And then I started to travel and get a more international view and began to compare things and reflect on the narrative of the human theater in a way. And there’s a never-ending fascination.

Research Vehicle

It sounds optimistic in a way—that curiosity about life.

I am not always a happy and jolly person, but by and large I always grant a certain optimism toward things and other people.

To go back to the earlier conversation, as much as I’m afraid and worried about the election of DT, as I call him—my wife is American and I come to America very often, and I’ve had many conversations with people here—I’m hopeful for the capability of resistance and the defense of the positive things this country stands for. And by that, I don’t mean the tireless misuse of the word “freedom,” because often it’s used in a very superficial manner.

Nature & Politics is on view at the Moody Center for the Arts through May 29.