#TBT: Mary Ellen Mark Talks Process With American Photo, 1998

Insight from the late legend on how she made some of her strongest pictures

Mary Ellen Mark, who passed away on May 25, 2015, was one the most frequently featured photographers in American Photo magazine’s history, with her images gracing more that half a dozen individual issues from the last quarter century. Upon news of her death, we’ve taken time to reflect on her legacy and dug through our archive to revisit her remarkable contributions to our own pages. Here, we present an exclusive 1998 interview with Mark about her progression through various camera formats, how she composes photos, and why her subjects place so much trust in her. Below, she talks shop with Russell Hart, former Senior and Executive Editor of American Photo magazine (1990–2011).

Master Class

Mary Ellen Mark

This renowned photographer loves the human animal.

By Russell Hart

October 20, 1998

Mary Ellen Mark is a rare breed: a documentary photographer with an instantly recognizable style. Whether she is shooting performers in an Indian circus or the down-and-out in America—subjects she often revisited—her work has a visual consistency that would be the envy of most art-world stylists. (American Photo readers chose Mark as their favorite woman photographer [in an previous feature from this issue of the magazine.]) Yet for Mark, style is not something to be imposed on a subject; she is even reluctant to bring a concept to a portrait. “I find that the subject gives you the best idea how to make a photograph,” she says. “So I usually just wait for something to happen.”

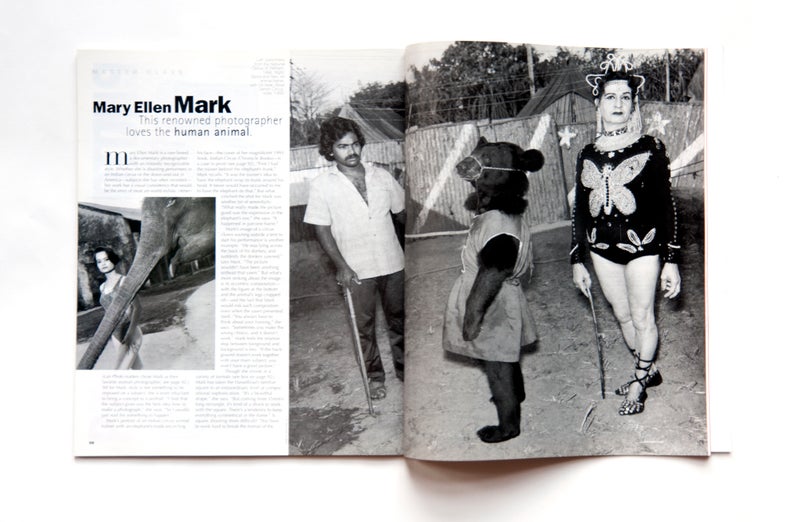

Mark’s portrait of an Indian circus animal trainer with an elephant trunk encircling his face—the cover of her magnificent 1993 book, Indian Circus (Chronicle Books)—is a case in point.”First I had the trainer behind the elephant trunk,” Mark recalls. “It was the trainer’s idea to have the elephant wrap its trunk around his head. It never would have occurred to me to have that elephant do that.” But what clinched the shot for Mark was another bit of serendipity. “What really made the picture good was the expression in the elephant’s eye,” she says. “It happened in just one frame.”

Mark’s image of a circus clown waiting outside a tent to start his performance is another example. “He was lying across the back of his donkey, and suddenly the donkey yawned,” says Mark. “The picture wouldn’t have been anything without that yawn.” But what’s more striking about the image is its eccentric composition—with the figure at the motto and the animal’s legs cropped off—and the fact that Mark would risk such composition even when the yawn presented itself. “You always have to think about your framing,” she says. “Sometimes you make the wrong choice, and it doesn’t work.” Mark feels the relationship between foreground and background is key: “If the background doesn’t work together with your main subject, you won’t have a good picture.”

Though she shoots in a variety of formats, Mark has taken the Hasselblad’s familiar square to an extraordinary level of compositional sophistication. “It’a a beautiful shape,” she says, “But coming from 35mm’s long rectangle, it’s kind of a shock to work with the square. There’s a tendency to keep everything symmetrical in the frame.” Is square shooting mode difficult? “You have to work hard to break the format of the square,” says Mark, whose dynamic compositions—square and otherwise—push and pull at the edges of the frame. “But each format has its own problems and solutions.”

All that said, for Mark, what’s inside the frame is still the most important element of photography. “Finding the right subject is the hardest part,” she says. Indeed, Mark’s ability to penetrate notoriously suspicious subjects—from prostitutes on Bombay’s Falkland Road to Irish gypsies—is legendary, and has been recognized with three NEA grants and a Guggenheim fellowship, 11 solo books, dozens of exhibitions, and countless assignments. Mark says she’s still learning about both the human dynamic and the craft of photography. “There’s only one reason I’ve stayed a photographer for so many years,” she says. “Photography is always challenging.” —Russell Hart

Mary Ellen Mark On Format:

Learning how to use different formats has made me a better photographer. When I started working in medium format, it made me a better 35mm photographer. When I started working in 4×5, it made me a better medium-format photographer.

The situation really dictated what format I use. The voice depends either on whether the subject will be enriched by detail or on how spontaneous I need to be. But even when I shoot 4×5, I try to break the format’s formality—to make the pictures looser. I’ve managed to to that with a few projects; one was photographing ballroom dancers in Miami. It’s risky shooting action with a large-format camera. You have to use a pretty narrow f-stop, a fairly wide-angle lens, and more that the usual amount of light—and be sure your shutter speed is high enough to ever ride the ambient light. For the Miami pictures, I would just prelight a certain area with Broncolor strobes and stop my 99mm lens down to f/22. That way. I didn’t have to hit my focus exactly, so the dancers could just move in and out of the area.

On Lighting:

I used to use no artificial light at all, and shoot everything in 35mm. That’s certainly a wonderful way to work. But when I started doing more portraits, I realized I couldn’t always just depend on existing light. Sometimes you have to work in the studio or a dim interior space and then you have to light it. So I’ve had to learn about lighting. And you learn by looking at light, and the way others use it. When I used to shoot on movie sets, I learned from lighting directors. I’ve learned from good assistants. And I’ve learned from my husband, a filmmaker. I’m not a great lighter; I’ve just learned what works.

I like lighting to be as inconspicuous as possible. Usually I try to add just enough flash to make the main subject stand out. But the subject and the brightness and the distance of the background really determine how much light is needed. It’s had to keep light subtle with dark circus animals, for example—subjects like the standing bear in the dress. You have to put a lot of extra light on them just to create enough sense of texture and detail.

On Trust:

Everyone asks me how I get my subjects to open up to me. There’s no formula to it. It’s just a matter of who you are and how you talk to people—of being yourself. Your subjects will trust you only if you’re confident about what you are doing. They can sense that immediately. I’m really bothered by photographer who first approach a subject without a camera, try to establish a personal relationship, and only then get out their cameras. It’s deceptive. I think you should just show up with a camera, to make your intentions clear. People will either accept you or they won’t.