The Story Behind Ken Jarecke’s Horrific and Controversial Gulf War Photo

The year was 1991. American Photo magazine was in its second volume of publication, John Szarkowski was reported to be...

The year was 1991. American Photo magazine was in its second volume of publication, John Szarkowski was reported to be stepping down from his 29 year tenure as Director of Photography at MoMA, and Tina Barney was yet a “Rising Star,” in the photo world, according our editors. Nikon was pushing a bicycle handlebar mount for their SLR camera, the light meter market was competitive, and the Holga was retailing for half the price it is today.

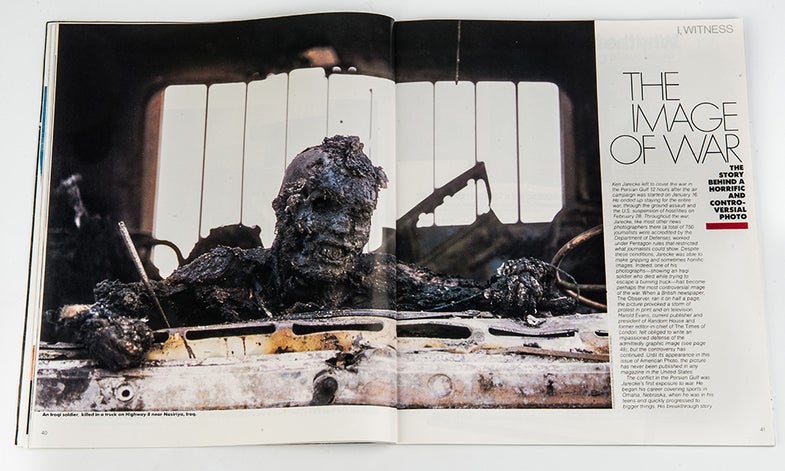

The year also marked the first of now three U.S.-led military incursions into Iraq. Ken Jarecke, then a contract photographer for TIME magazine, was on the ground hours after the launch of the air campaign on January 16 and continued documenting the conflict through the ceasefire on February 28. Despite the tight restrictions the Pentagon placed on journalists, Jarecke managed to shoot a number of horrific, but revealing images of combat and its consequences. One of his most brutal photographs, a picture of an Iraqi soldier burned alive in his truck, stirred huge controversy over the representation of conflict in the news media. Photo editors wanted nothing to do with it, American wire services pulled it from the domestic syndicate, and until its appearance in the pages of that 1991 summer issue of American Photo magazine alongside Jarecke’s backstory, the photograph had never been printed in the U.S. Its notoriety grew, and eventually it became the iconic, lasting image of the war.

Twenty-three years later, the photo no one wanted to publish is in the news again as yet another U.S.-led bombing campaign gets underway in Iraq. Though we live in an era saturated with gory imagery, critics and journalists are repeatedly turning to Jarecke’s gruesome 1991 photo and the kicker to his story: “If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.” The noted photo scholar Fred Richin quoted it in TIME, as did art critic Carolina Miranda in the LA Times, and writer Tory Rose DeGhett repurposed it for her long feature in the Atlantic magazine.

Here, we republish Jarecke’s first-person account of making the photograph, as told to then Senior Editor Carol Squiers.

The Image of War: The Story Behind a Horrific and Controversial Photo

July/August 1991

The first several weeks after my arrival in Saudi Arabia were uneventful, tedious even—though that changed later on.

During the air war, photographers had nothing to shoot; we were sent on press junkets here and there inside Saudi Arabia that were arranged by the U.S. military, the Saudis, or the Washington PR Rim retained by the Kuwaitis. Eventually I was assigned to a new pool—a collection of photographers, reporters, and TV crew that had to travel together while supervised by press affairs officers. That was how the Pentagon controlled coverage of the war.

My pool was attached to the XVIII Airborne Corps. At first, we did little besides sit in a strip of contested land at the Saudi-Iraqi border for two weeks.

Then, on February 23, the day before the ground war began, the corps moved 40 Kilometers into Iraq. My pool, which traveled in a Nissan van and a Humvee (an HMMWV, actually, the replacement for the jeep), included a crew from CBS, a writer and two military public affairs officers. Once we started moving, we still weren’t seeing much combat; we’d do “fire missions”—the troops would move to a position and fire howitzers, say—but there was never any counter fire. Still, there was lots of confusion and we had very little time to work.

A typical picture-making situation occurred that day, when I made a photograph of a burning Iraqi tank that had been hit by U.S. bombs. I saw smoke as we were driving, and I asked our press officer to take our car out to the right of our convoy so I could make a picture. Ammo was burning and blowing up and the convoy was moving fast. We stopped, I made my shot, and as I turned to get back into the car, the tank I’d been photographing blew up, so I turned and photographed it again. The whole episode took five minutes, tops.

Ironically, it wasn’t until after the cease-fire on February 28 that I made the picture that’s been so controversial—the dead Iraqi soldier. By then, my press pool was traveling alone because the cease-fire was in effect—although we heard there was still fighting going on. We were in Iraq, and instead of going to see the fighting—Republican Guards were nearing us trying to get to Basra—the CBS crew wanted to go back to Hafar al-Batin in Saudi Arabia. We got on an interstate at a point 80 kilometers from Kuwait City. We stopped at about 9:30 in the morning and photographed some U.S. medics tending wounded Iraqis, although we weren’t supposed to photograph casualties. Then I noticed something: a body lying in the road. We’d passed other bodies on our trip, but I hadn’t stopped to make pictures. There is no reason to make a body picture unless there’s something compelling about the scene. Now I thought what I was seeing was compelling.

While still in our vehicle surveying the scene, one of our press affairs officers told me that making pictures of dead guys didn’t elate him. I told him it didn’t get me off either and that it didn’t make my mother proud to see my name under those kinds of pictures. But I told him that if I didn’t make these pictures, it would be a distortion of reality: People would think war is only what you see in movies. He knew that I was going to make the picture, but he had to put his two cents in.

Down the road just a little farther, there was a truck that had been bombed while trying to escape from Kuwait into Iraq. I made a shot of the truck from where I was standing using a Canon EOS-1 with a 35mm lens. There was a guy lying in front of the truck, and I couldn’t figure out how to photograph the whole scene because of how it was completely backlit. It was a while before I noticed the burned guy in the truck. Evidently he’d been trying to crawl out through the windshield when the truck was hit. I changed lenses and shot some black and white and some color and got back into our vehicle and we left.

I wasn’t thinking at all about what was there; if I had thought about how horrific the guy looked I wouldn’t have been able to make the picture. I just concentrated on technical problems: I’m at 1/60 second at f/2.8 with an 80-200mm zoom lens, so I have to be really steady. And it’s backlit, so I have to be sure the focus is right there. I had to use the 200 because of the body in front of the truck; I’d have had to step on the body to get close enough to shoot with my 35mm lens.

There were bodies scattered all along that road, but I didn’t take pictures of any of them. I couldn’t show more than I already had.

I didn’t start thinking of the picture as significant or symbolic, though, until later, when I was talking to Jim Helling, the CBS cameraman in my pool. He had shot footage of that truck and those bodies too. He said he wanted a print of the soldier in the truck. At first I didn’t understand why. When I asked him he said something that really hit me: “Because that’s the face of war.” He had realized how powerful the scene was immediately.

After the cease-fire was fully in effect, our pool was dissolved. We started driving back to Saudi Arabia. We got lost at one point—we spent half our time being lost—and inadvertently drove through a mine field. When we finally found the road we needed, we thought, fine, Kuwait City, 60 kilometers ahead. I fell asleep.

When I woke up we were stopped in the middle of a big junkyard full of burned-out cars, buses, and trucks. But it wasn’t a junkyard. Bodies were everywhere, engines were still going. I could hear a radio playing in the distance. Machine guns were set up in firing positions. We managed to zigzag our way through the mess and got to Kuwait City at 7 a.m. From there we caught a ride to Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, arriving about 8 p.m.

I was dead on my feet. But I edited my film and turned it in to the pool for Reuters and the Associated Press to put on the wire. Then I went back to my hotel and passed out.

The next day I was talking to a producer from one of the TV networks. She told me the “junkyard” we’d passed through was in fact a seven-mile-long wreckage of Iraqi vehicles fleeing Kuwait when they were bombed by the U.S. She also said there were so many cluster bombs on the ground there that a group she had been with couldn’t even walk through. We were incredibly lucky.

I’m glad I did this, but I wouldn’t go to war again any time soon. I can’t stand feeling the fear all the time. And as a photographer, I started to get ticked off about the picture of the burned Iraqi before I even got home. I figured it would never get published in this country. In fact, when the Associated Press in Dhahran transmitted the picture, some editor in New York took it off the wire. It wasn’t even distributed in the U.S. until my agency got it. But I think people should see this. This is what our smart bombs did. If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.

Ken Jarecke is an American photojournalist living in Montana. He is a former contract photographer for TIME and U.S. News & World Report, currently represented by Contact Press Images.