Shooting Drugs

It was never completely clear whether I was officially deported from Djibouti or merely kicked out. Either way, I probably...

It was never completely clear whether I was officially deported from Djibouti or merely kicked out. Either way, I probably shouldn’t stamp my passport there anytime soon. Even before I went people couldn’t figure out why I was going. That included the Djiboutian official who issued my visa. “No one visits Djibouti, Mr. Peter. Why do you travel there?” he said.

I was going because Esquire was sending writer Kevin Fedarko and me to cover the khat trade. I’d been to the former French colony before, on assignment for National Geographic, so I knew about its strange combination of bureaucracy and lawlessness. I also knew about khat, which is impossible to miss there. Also known as qat, chat and miraa, the shrublike plant is grown in the highlands of Ethiopia and Kenya. Claimed to ease both the heat and one’s troubles, it’s an addictive stimulant that offers an intense rush followed by an introspective, sometimes hallucinogenic torpor. And a lot of people are on it. Around half the adult male population of Djibouti consumes khat, and many use it daily.

Another unique characteristic of khat is that it begins to lose its potency just 48 hours after it is picked. Consequently, in the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, it is the one commodity that shows up on time. In war-torn spots like Somalia, the khat plane is the only one that doesn’t get shot at. Every day when the khat shipment lands in Djibouti City, it sparks a nationwide frenzy of distribution and consumption. In roughly 46 minutes each day, 11 tons of the leafy narcotic gets distributed across the tiny country. By 1:30 p.m. most users are into their first mouthful and feeling their oats. By 2 p.m., the country’s daily khat ration is gone and the decaying capital city descends into a somber, stoned daze.

Appropriately, Kevin and I arrived from Dire Dawa, Ethiopia on the khat plane itself, a 1966 DC-8 with a faded gorilla emblazoned on its tail. On landing, the khat distribution crew waiting on the tarmac nearly tore the plane apart in the scramble to get their prized foliage to market.

We spent our first afternoon securing official press papers from the Djiboutian trade authority. The smiling man who handed us our documents said, “Very good you here, you must brouter la salade [try the khat].” On the street, however, the atmosphere was decidedly less hospitable. The combination of poverty, drug use, unemployment, stifling heat, crumbling colonial architecture, rampant prostitution and various flavors of soldier was unsettling at best. Add to that a legion of screaming khat vendors and the world turning upside down for two hours every afternoon, and it’s a recipe for great pictures. Getting them, however, was far more difficult than I’d anticipated.

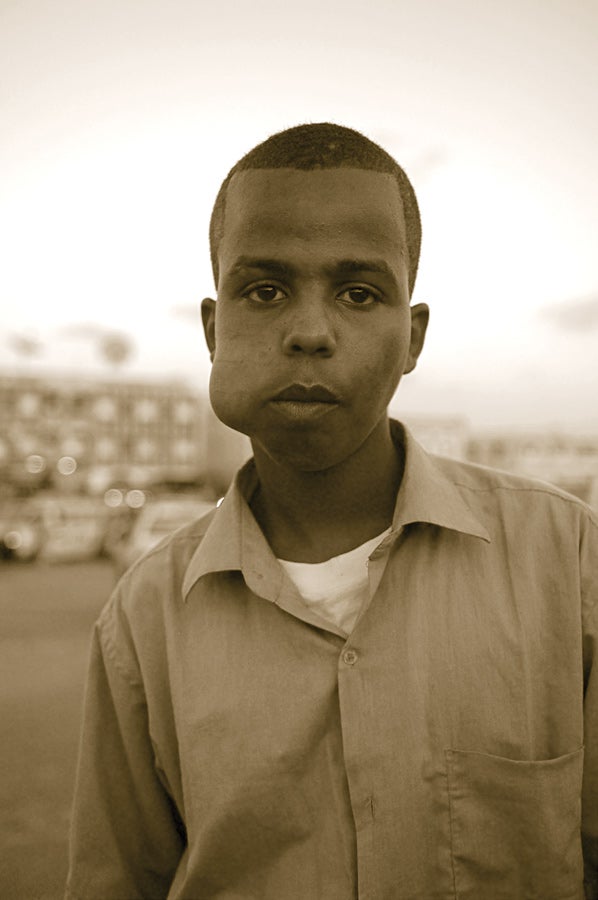

Despite (or perhaps because of) my press documents, clearly typed in Arabic and Somali, the khat traders despised me, afraid I was there to put a stop to their livelihood (despite its complete legality). Wherever I shot, I was attacked, sometimes with insults in Somali, other times with rocks, fists or even bags of khat. By day three I was paying young kids to watch my back.

By day four, paranoia had started to nibble at me. I sat in our hotel in an adrenaline eddy, steadying myself with deep breaths and internal monologue. “One foot in front of the other. Almost there. Clear off your cards. No freakouts.” I had recently changed from film to digital and was still working out my archival workflow. However, just as I started transferring the shots from one card onto my battery-powered hard drive, someone started pounding on our door. We heard agitated voices in the hall. Kevin opened it to find Abdul, a khat trader we had met, red-faced and frantic, backed by a much larger man we didn’t recognize. Abdul wanted us to go with him. “No problem! You bring camera. No problem! They look. No problem! We go now.” It was the least calming usage of the phrase “no problem” I’ve ever heard.

“We go as soon as my camera is charged,” I fibbed. I needed to buy some time to get these images transferred. “No camera, no see.” For five minutes, he paced as my card slowly spooled its contents onto the hard drive and I pretended to fret over my fully charged Nikon. In the meantime, Kevin phoned our U.S. embassy contact under the guise of asking for translating help. The embassy told him not to leave the hotel. This is easier to do when you’re not standing in front of two hopped-up khat fiends, one of whom has a gun.

Without warning, Abdul had had enough. His mouth bulging with green, he clutched my arm and shouted, “We go!” I responded almost as loudly, “Re-lax!” As I grabbed my camera, I stuffed my portable hard drive, card still inserted, deep inside my pocket. I could feel it spinning against my thigh—a muffled vrrrrt, vrrrrt, vrrrrt buzzing through my pants.

We drove five dusty blocks to a military building where two machine gun–wielding guards escorted us into a high-ceilinged office. A quiet man in formal military attire greeted us. He had heard I was photographing the khat trade. “Give me camera,” he said calmly. I handed it over. The hard drive whirred away in my pocket. He silently paged through my shots, then asked to see more.

The card in the drive hadn’t finished transferring. With a mental wince, I reached into my pocket and yanked it out. Then I swapped it into my camera and handed them over for inspection. As he reviewed, I slipped my hand in my pocket and slotted the untransferred card into the drive by feel, groped for the large download button, and coughed as it resumed whirring. Abdul was staring at me in a way that made me nervous, but he was quickly distracted by the sudden entrance of a stocky, shaved-bald American, a representative from the embassy. After our call he’d come to check on us and found us missing. Apparently the hotel desk clerk had noticed our unorthodox departure and clued him in to our whereabouts.

A heated discussion broke out. My hard drive hummed against my leg as Somali was spoken, then Arabic was shouted, French was screamed, and finally English was bellowed.

I said a silent prayer to the gods of battery life as I watched the chaos unfold. I knew how these scenes always ended: with the words “Turn over the photos.” Back when I used film, I had a system. An official would request the pictures and I would hand them fresh, unshot canisters of film that I’d wound into the spool and written on to make them look ready for developing. As they triumphantly exposed dummy stock and I pantomimed defeat and frustration, the real rolls would be down my pants, or better yet, in the mail to myself back home. This was different. Digital gave them immediate access. They knew exactly what I had. They just didn’t know where else I had it.

I tried in vain to follow the arguments until Gary, our new friend from the embassy, turned to me and said, “This is the head of national security. He says you will go to jail unless you turn over the imagery and leave the country today. I’ve pushed it as far as I can. You should go. Right now.”

The drive in my pocket had stopped spinning moments before, either because it was finished or because its battery had died. I popped the card from it and handed it to him along with the one in the camera. I had no idea how many photos had made it onto the drive.

Another hot, dusty car ride later, we were at the airport, escorted by Djiboutian soldiers. My belly twisted like a chain of fish hooks as we approached security, staffed by a man chewing a large green ball of khat. As he performed a half-hearted hand check of my camera bag and laptop case, it became apparent that he was on the languorous back half of his khat buzz. As he patted me down, though, he brushed against the hard drive and grunted quizzically. I pulled it out partway and replied, “Computer.” He nodded, and back in my pocket it went.

Relief washed over me as I moved past him. We thanked Gary and boarded our flight. I didn’t check the photos until we were at our hotel in Ethiopia. Smuggling is a dodgy business. You can never be too careful. AP