In the Shadow of the Black Sun

Chris McCaw wakes up and pulls back the window curtain inside the hollowed-out cargo cab of his Dodge Sprinter van....

Chris McCaw wakes up and pulls back the window curtain inside the hollowed-out cargo cab of his Dodge Sprinter van. The summer sunlight leaks a dim glow through the windows. He’s driven this van nearly 3,500 miles from San Francisco to Alaska’s North Slope for the chance to make a photograph. It’s time to start.

Waiting outside on a custom-modified cart is McCaw’s unique homemade rig. It is a camera only insofar as it is a box that lets in light through a lens and projects an image onto a photosensitive medium. After that, all similarities end.

McCaw loads the first sheet of photo paper into its holder. It’s vintage stock, 30-by-40-inch gelatin-silver stuff he searches out from Craigslist and eBay. Everything else associated with McCaw’s rig is supersized to accommodate this gigantic medium, including the Sprinter, which he refers to as “the most expensive changing room in the world.” With the lens pointed at the brightening sun, he opens the shutter and begins the first of three 240-minute exposures he will make today.

Four hours later, as the sun continues to climb through a cloudless sky, a thin stream of acrid smoke begins to issue from McCaw’s giant camera. Like a kid’s magnifying glass held over an anthill, the lens focuses the sun’s rays, making them strong enough to scorch the paper. McCaw is ready. He opens a small slit in the side of the camera’s bellows and activates a solar-powered fan (the kind normally used to cool computer CPUs) to help vent the contrast-killing smoke. At the end of his first exposure, McCaw quickly closes the lens, repositions the camera and deftly swaps in a new sheet of paper for the next. Apart from that, he waits, making sure his art is only ever so slightly on fire.

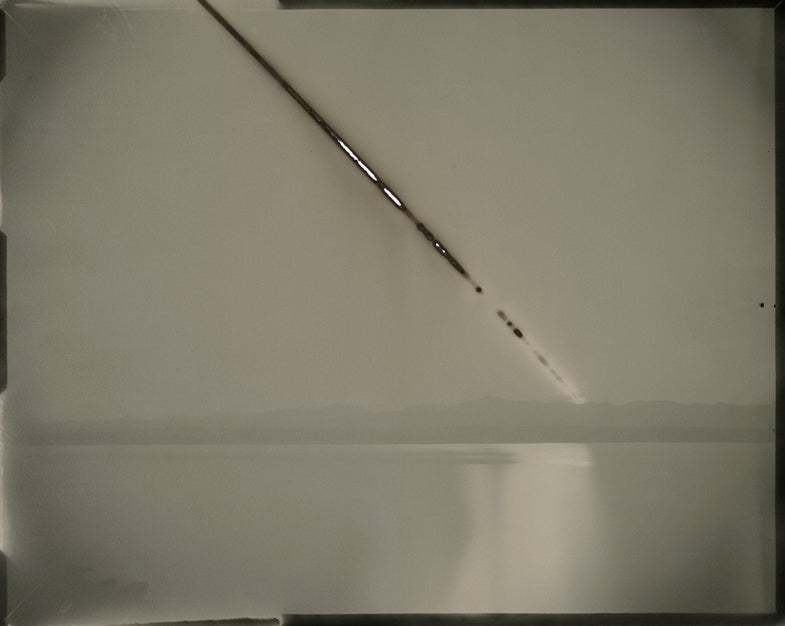

Once they’ve been developed and hung together in sequence, the three unique paper negatives will chart the parabola of Arctic Alaska’s never-setting summer sun as it arcs across the landscape. But instead of a bright white dot in a gray field of sky, in McCaw’s images the sun is a long curve, charred black at the ends.

Sunburned GSP#486 (Sunset/Sunrise, North Slope, Alaska)

McCaw’s work is part of a loose canon of photography made by those who enjoy turning one of the most reliable constants of both life and photography on its head. Over the decades, these photographers have sought out—or, often, stumbled upon—ways to subvert the mind’s powerfully ingrained notions of how the sun should look. The result is a compelling mixture of landscape photography and cognitive dissonance.

One of the most famous intentional black-sun photos was made by Ansel Adams. Writing in his 1983 behind-the-scenes book Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs, Adams recalls his 1939 photo “The Black Sun” as a “striking surrealistic image.”

“It was proof,” Adams writes, “that the subject may prompt ideas, ideas crave visualizations, and craft makes their realization possible.”

The craft in question is a technique called overexposure solarization. With typical black-and-white film or gelatin silver paper, exposure to light creates a chemical reaction that turns some of the silver-halide crystals in the film grains to metallic silver. In development, the metallic silver areas appear dark on a film negative, rendering them white in the print. The greater the exposure to light, the more metallic silver is formed in the negative, creating a greater density of black.

However, all photographic films and papers have a maximum density point. When they pass this point—typically in response to extreme overexposure to light—changes within the crystals cause the latent image to be destroyed and reduce the area back toward zero density on the developed negative. Those areas become translucent (on film) or white (on most photo papers, although some papers will flip from black to white multiple times as they are overexposed). At the enlarger, these areas on the negative print black. In landscape photography, the brightest part of any scene is almost always the sun, so that’s generally the first thing to flip back over to black.

The Black Sun, Owens Valley, California

Ever the technician, Adams writes in Examples that he had visualized the scene he encountered in Owens Valley, California, with a surreal black sun and intentionally overexposed the negative to achieve the effect. But it’s easy to see how extreme overexposure could happen by accident. Such was the case with another 20th-century master, Minor White. His own black sun, rising somewhat ominously above a frozen barn in a famous 1955 image, came thanks to a slow shutter on what looks to be a freezing winter day. Of the resulting shot White said, “The sun is not fiery after all, but a dead planet. We on earth give it its light.”

The Probatic Pool, Jerusalem

As an error, the phenomenon of overexposure solarization dates back to the dawn of photography. Early daguerreotypists had to take care not to overexpose their portrait subjects’ white shirts. If they did, the unique chemistry of the daguerreotype process turned those areas blue. Some early landscape daguerreotypists, such as Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prongey, used this form of solarization intentionally, overexposing the sky to render it a surprisingly true-to-life shade.

Ever since the emergence of commercial film, manufacturers have been trying to increase the light tolerance of their product, reducing mistakes and allowing photographers to create realistic images under increasingly extreme conditions. As a result, today’s black-sun practitioners often reject modern film stock and papers in favor of harder-to-find materials whose limitations, perversely, have become assets.

German photographer Hans-Christian Schink came across Minor White’s “Black Sun” as a young boy growing up in East Germany starved for Western images and media. At a book fair in Leipzig, he “liberated” a copy of Time-Life’s Great Photographers and was mesmerized by White’s image.

As Schink’s own career took shape, the black sun inevitably found its way into his work. Similar to McCaw, Schink didn’t just turn the sun black but rendered it as a streak across the sky by using long exposures. But where McCaw’s black-sun exposures sometimes push 24 hours, Schink exposed his for precisely one—hence the title of his book, 1h (Hatje Cantz Verlag, $85).

The precise timing of each photograph became the constant in his work. As he refined his methods and traveled the world in search of natural landscape backdrops, Schink says, his hour-long exposures became meditative. “In all of my other projects I always tried to have a really technically perfect image,” Schink says. “With this project, I had to learn to just let go.”

7/14/2007-7/15/2007, 11:28 pm – 0:28 am, N69° 37.661′ E018° 13.470′

Asked if he found a similarly Zen solace in his process on the Alaskan tundra, McCaw replies that the experience is precisely the opposite for him. “There’s really no relinquishing of control when you’re using a 30-by-40 camera you built yourself,” he says. “To me it’s not about relinquishing control. It’s more of a collaboration. It takes a lot of work to make these images.”

For some of his photographs, McCaw has made a sequence of exposures as long as 24 hours. To capture a day-long stretch of pristine sunlight, he made two trips to Alaska’s North Slope. Over five weeks he aborted several attempts—one 17 hours in, after an unexpected summer rain shower blocked the sun.

McCaw is also at the mercy of his materials. The vintage photo-paper stocks that solarize to his liking are hard to find—so much so that he keeps brand names to himself to avoid crowding an already limited market of buyers. And then, of course, there’s the burning. The singed streaks blend nicely into the black, traditionally solarized lines of sun.

“In a way I feel like I’m physically working with the light,” McCaw says. He uses no enlarger and makes no prints. The light of the sun touches his paper, at times burning through it, and that paper goes on the wall as a one-of-a-kind negative.

Thodoris Tzalavras, a Greek photographer living in Cyprus, also builds his own cameras to produce black-sun images, but on a much less dramatic scale. To tell the story of drought-prone Cyprus’s strained relationship with water, Tzalavras turned to homemade pinhole cameras to capture sweeping landscapes of riverbeds and canyons that had been carved by water over millennia.

Tzalavras’s 4×5 pinhole camera provided a connection to his ancient subject. When one of his early exposures on Harman Direct Positive paper came back with a darkened sun in the center of a dramatic cloudburst, Tzalavras was thrilled.

“It transformed the whole picture,” Tzalavras says. “You expect the sun to be something. When it’s the opposite, the landscape takes on something otherworldly. It fits into the project as another expression of the power of nature.”

While it is less common, some color films will also solarize the sun and surround the powerful black dot with richly colored skyscapes. Amelia Konow, a photography student at the San Francisco Art Institute, used a Polaroid Automatic 100 Land Camera with thick-emulsion Fujifilm FP-100C pack film for her project Thirteen Black Suns. The instant-print film renders a solid black disc with a soft edge resembling a solar eclipse.

Black Sun #11

Interestingly, the black sun is not the exclusive domain of hard-to-find films, homemade cameras and expired photo papers. While taking simple snapshots with his camera phone, Harlan Erskine, a Brooklyn–based photographer, found that when aimed straight at the sun, the image sensor in his Palm Treo 600 (and later with the Treo 650) would become overloaded, flipping white pixels to black and creating an effect similar to overexposure solarization.

What began as an accident became a regular practice. Erskine made a formal exercise, and eventually a daily routine, out of his glitchy black sun photos. Three years and nearly 1,600 images later (most of them shot as a creative respite during long hours at a day job in advertising), Erskine had a body of work he was able to show at an art space in Miami. It wasn’t until it came time to write the accompanying text for his photos at the space that Erskine ran across the black suns of Adams and White. Erskine was stunned to discover that his own work, with its accidental origins, fit into a rich subgenre of photography he didn’t even know existed.

Black Sun 0181

It’s not surprising that so many artists would latch on to such an aesthetic, often independent of one another; it evokes a powerful image. The sun is one of the few ancient and universal constants on this planet, as fundamental as air, water and earth. We may be just a few DNA sequences removed from chimpanzees, but the sun as a force for life goes all the way back to the earliest bacteria that were incubated in its warmth. When it goes black, all our expectations are flipped, conjuring unconscious reactions to the archetype and myth of the eclipse.

It’s fitting, then, that making such images requires physical struggle. It takes power to turn the world upside down. Through the transformation of crystals, overloading of digital circuits and burning of paper into ash, our monkey-mind gets the briefest recollection of staring uncomprehending into a sky unexpectedly darkened. We return from the experience changed, the fire of our quest for meaning rekindled. AP