Recontextualizing Robert Frank

Exploring the photographer's work beyond The Americans.

Don’t Blink, a new documentary about Robert Frank, will come as a surprise to anyone who knows of the photographer only through his seminal book, The Americans. Directed by Laura Israel, Frank’s film editor since the ’80s, the film had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival this past weekend. Frank, now 90, was an active participant in making this doc and what emerges from he and Israel’s on-set collaboration is multifaceted. This is Robert Frank the funny guy, the experimental filmmaker, the fan of the ’60s Beat scene. What also emerges is Frank’s embrace of creative work as the antidote to personal tragedy.

Don’t Blink includes interviews with people who worked with Frank, like his darkroom assistant Sid Kaplan and poet Allen Ginsberg, as well as footage of Frank from various stages of his life. It also features gorgeous full-frame representations of his still photographs and clips from most, if not all, of his movies, including the legendary Cocksucker Blues, commissioned—and buried—by the Rolling Stones, and Pull My Daisy, a silent film with voiceover by Jack Kerouac.

Not surprisingly, Don’t Blink begins with The Americans. “I started with The Americans because I wanted to use it as a departure point into his other work and to show that he moved on,” explains Israel. “The Americans enabled him to do all this other stuff, and I’m hoping that it opens the door for people to see his other work.”

Through interviews with Frank, she covers his early years in New York, raising two kids with Mary, training with Walker Evans, working for Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar to pay the family bills. “Little by little, I knew what I could get: Pictures that talked about the character of the people,” Frank says in the film. “As a photographer, you have a certain time that’s good for you. The best time for my photography was also the hardest: I had to support my family.”

Frank moved on from his life in New York. He left Mary for artist June Leaf and fell in with Ginsberg and Kerouac. He switched from still photography to film. He and June moved from New York to an isolated cottage in Mabou, Nova Scotia. He lost control of the rights to his negatives, including The Americans. He hooked up with Stewart Brand, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, and Julian Beck and the Living Theatre, back in New York. He went through unspeakable pain—the kind that no parent should ever have to bear.

The more tragedy befell him, the more his work turned from observation to self-expression. He returned to photography in the ’70s, painting words on his photographs or scratching them into the negatives. “Words,” he says in the film, “are for people to understand more what the artist is saying.” Consider a series of shots of a wooden pole outside his house in Mabou, “For Andrea Who Died 1954 1974” inscribed over them, or “Sick of Goodby’s,” in Frank’s book Lines of My Hand. He’s right; the words, rather than the images, make his grief plain as day.

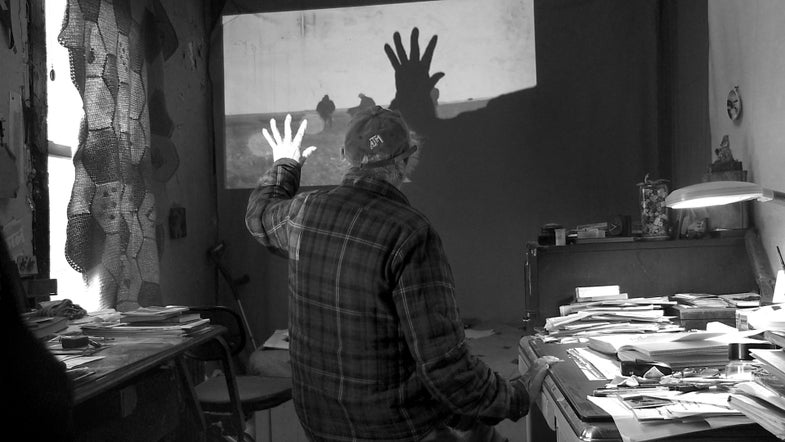

Frank never stopped shooting though—it was as if the act itself propelled him from a painful past into an unknowable future. “I believe in fate,” he says, “but you deal with fate by believing in work.” This is the man that Laura Israel captures in Don’t Blink: a man who never stops creating. “Stand up,” he says. “Don’t shake.” And, most of all, “Don’t blink.”