Interview: Duane Michals on 50 Years of Sequences and Staging Photos

Through February of next year, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh is hosting the first major survey of the...

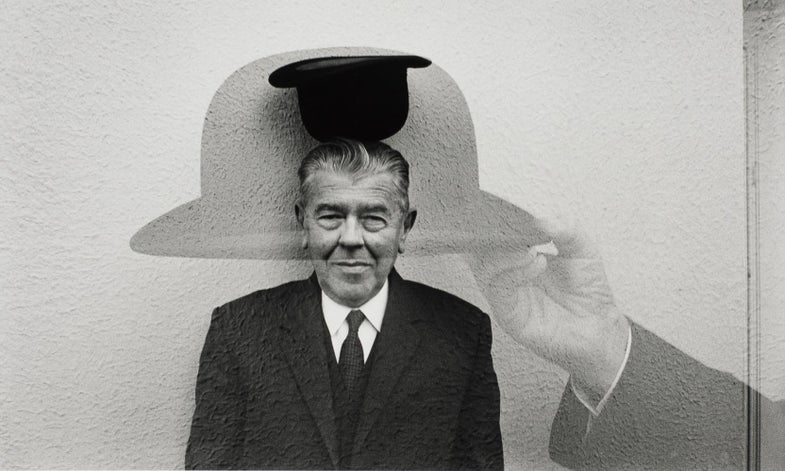

Through February of next year, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh is hosting the first major survey of the pioneering photographer Duane Michals’ work in more than 20 years. “Storyteller” covers nearly six decades of photographs from his first encounter with the camera in 1958, through his iconic narrative sequences or “mime fables” of the late 60s and 70s, up until the colorful, painted-over tintypes he’s been making in recent years.

Michals (b. 1932) has continually rebelled against and expanded the documentary and fine art traditions. At the onset, he baffled critics who knew not what to say of his work, rejecting the notion of the “decisive movement,” the supremacy of the sensational singular image, and the glorification of the perfect print. As an expressionist, rather than going out into the world to collect impressions of the eye, he looked inward to construct the images of his mind, exploring the unseeable themes of life, death, sensuality, and innocence.

Shooting mostly Tri-X in available light, he’s maintained a simple process all these years, whether it was for his personal work, or for the commercial work that supported it—the LIFE magazine cover, the ad campaigns for Microsoft and Pampers, an album cover for the Police. Once a radical outlier, now a father of dominant trends, he inspired generations of photographers from Jim Goldberg and Cindy Sherman, to the countless others staging, scribbling over, and painting on their photographs today.

One afternoon, I met Michals at his stately home studio just off Park Avenue in New York. Affable though pensive, he wore a salmon-colored work shirt, sitting across from me at a small table in soft window light, with a Joan Miró hanging overhead, and faint orchestral music resonating from another room. The following is an edited version of our conversation about why he’s glad to have never studied photography, what annoys him about photographers who call themselves “artists,” and what drives him, at 82, to keep making new work.

What was it like going back to Pittsburgh, where you were raised, for the opening of this retrospective?

It was crowded and enthusiastic. For me it was going back home. I love that the exhibit is there; that’s where it should be because that’s where I started out. I’m not one of those people who turns their back on where they came from. My blue collar roots I’m very proud of. People showed up from high school, friends from around the country. It was lovely. At 82, the eagle has landed.

Did you frequent the museum when you were living there?

Absolutely. When I was a kid in high school, they had Saturday drawing classes. So that was really exciting. I didn’t come from—I mean, maybe we had a phonebook in our house, but my background was certainly not reading, writing, and arithmetic. It was a steelworker background. You go to work, you do your job. On Christmas, you have a shot of whiskey and a beer. You know, like that. I liked it as a kid, and I still do.

But then you moved away to college?

I ran away. They gave me a one-way ticket.

Your parents weren’t thrilled with you studying art?

No they were not not-thrilled. But they told me I have to be practical. So I took Art Education. It covered all the bases but it had nothing to do with photography.

You’re quoted in the catalog saying you’re glad you didn’t study photography because you didn’t have to unlearn all the things they tell you not to do.

That’s the most difficult thing is unlearning. I always tell students you’re either defined by the medium or you redefine the medium. And most people are defined by the medium, those are the rules you are taught. That’s ‘public domain’ photography, things we would all agree is photography—reportage, walking around photographing, weddings… photography as observations of life, going through life observing, finding things, making discoveries—that sort of thing. But it’s all exterior. I simply turned the glove inside out. For me it was all interior.

Would your advice to a young artist be to avoid the academic setting?

No. It’s hard to give advice, but there are certain principals. Advice is, ‘don’t do this, don’t do that.’ But principals are… first of all, you should always stay open to every experience that comes your way. A lot of experiences will be strange and alien and scary and that’s the very reason you should search them out and investigate them. If you only stick to the familiar, you might as well get back in the womb.

Our lives are filled with experiences. For instance, I didn’t want to go to the army, but I had to go to the army. So we encounter all kinds of things and it’s how we respond to them that gives them their significance. So always be open to new experiences and once they occur, don’t be afraid because being creative is based on fear—you don’t know what you’re doing. If you already know what you’re doing, you’re not really being creative. Creativity is the discovery that you make in the process of evolving. So that’s essentially the most important thing to me, to always stay open.

What was your military experience like? What did you take away from it?

It was during the Korean War. I had never seen a tank in my life, I was 21 going on 12. Luckily I was sent to Germany because if I had gone on to Korea I wouldn’t be here today. The turnover was phenomenal. Still it was the most alien experience of my life. The second, and maybe even the first now, is dealing with old age. But that was number one. Can you imagine going some place to do something you don’t want to do every single day for two years? With the possibility of being killed in the process? It was horrifying.

I did a book on it, on my personal letters from that era, The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon. I’ve always been very lucky that I’ve been able to feed off of the events of my life. I never needed to go someplace exotic to take faces. Photographers always photograph other peoples faces, something they know nothing about, and the one thing they know something about, is their own truth. You don’t have to go someplace exotic where you’re distracted by colors and costumes and stuff. The simplest facts of your life are really quite amazing and exotic. Basic facts of being are very strange and overwhelming; that’s why we avoid them most of the time by distraction.

You’re quoted saying, “I was always jealous of painters. Magritte could have people raining out of the sky and I simply could not do that.” With the coming of the digital revolution in photography, that fact is no longer true; you can as a photographer have people raining from the sky. How have you received these innovations and how has it affected your work?

I have nothing to do with it for the most part. But I did do a series I called “Deconstructed Photographs” where I took a picture and rearranged the content. I did all that on a computer with a guy I work with that’s really fantastic. That was about five years ago. I’m going to make a commemorative photograph for this Pittsburgh exhibition and for that I’ll need a computer to put together. So I use a computer on occasion, but I never use a digital camera. Just Tri-X and available light.

You’ve said that you prefer seeing your work printed in a book, as opposed to exhibited on the wall.

Yes, I love books. I’m not interested in the perfect print. Exhibits are nice, but you leave the picture in the rooms when you leave. But if you have a book, you get to take it home, you get to feast on it.

How then do you feel about the presentation of your pictures on the internet?

It’s okay. I don’t think much about it. I do like the work to unfold. At an exhibit I would stand and read the whole series. But I like the punchline to be something else. On the internet, you see the picture sequentially, you can’t see them all at once, because they’re presented one by one [in a slideshow or on a scroll]. So that works.

For me I enjoy seeing an exhibit, but the book with remain for a long time and that’s important to me. I don’t think about an audience. I’ve always just worked in terms of myself. I don’t really realize there are people out there that see this work. I live very quietly. My tastes and the way I set up my life is really turn-of-the-century. I love books, I like reading, I like poetry. I have nothing to do with contemporary tastes, what’s hot and what’s not hot. I’m in my little time capsule, which is very cosy. It suits me.

The internet has also reinforced the supremacy of the strong singular image, with so much competing for attention. It must be difficult to make quiet, considered images stick nowadays.

I always said I want my photographs to whisper. Whereas a lot of photographs shout to get attention. Now there are big eight, seven-foot photographs—that’s shouting. A little print you have to come up to—’Say what? Tell me?’ It’s a whole different experience.

Do you think you brought that into your commercial work?

No, no, commercial work is, I’m paid to do pictures for somebody, and when I do my own work, I do my own work. I never want my own work to support me. That was never an option. I did my own work for my own pleasure. Young people somehow think they’re going to graduate and get their portfolio and somebody is going to have an exhibit and they are going to sell $30,000 photographs and they’re going to be Cindy Sherman—that’s a big mistake.

I always did commercial jobs, and since I had no education in the field, I learned everything on the job. I did Pampers ads for Christ’s sake. I loved doing all that. For me to do my own work, there’s a certain natural comfort to it. I know the territory, I know my needs, I know what I’m trying to say. But when you get an assignment, you don’t get asked back if you don’t produce. You’re there to satisfy their needs as a client. Doing a job that was really alien to me, like Pampers ads, I like the challenge, especially since I never use strobes. I had a lot of limitations, so I had to figure out how to do it. I never wanted it to be a business, i never wanted to have a studio, 17 assistants, and overhead of $20,000 a week. I made everything my own scale.

If your work is characterized by quietude, why would a brand like Pampers or Microsoft approach you to do a commercial?

Because I’m a good photographer. I could only do my own work within my own context; I rarely got called into a job to do within my own style. I’ve done LIFE covers, all kinds of things that you would never know was mine—Carly Simon album, the Police. I did a campaign for Mass. Mutual that went on for nine years, Scientific American for five or six years… I was able to deliver consistently. I like the challenges.

Whats you’re working process like today? Are you still making work?

Yeah, I’m going to have a spring exhibit at DC Moore. I’m still painting on photographs, tintypes and other things. It’s going to be in April and it’s all new material. I still shoot film, all film. I don’t have a digital camera. I work the way I’ve always worked. I haven’t changed anything. Once I had the idea, that was the most important thing. When something would just catch my imagination, I pretty much have it in my mind. It’s worked all these years… I’m not about to change.

But what has changed is the art world. And how the work is received and recognized.

There was no art world when I started out. The art world was originally… the first little gallery was called the Image Gallery, on 10th Street, and that lasted for maybe five shows. And then there was the Underground Gallery, and Norbert Cleaver ran it. It was on 10th street as well, but he lived in the basement of this building and the gallery was the hallway going to his apartment in the back. That was it. But then it was Lee Witkin who invented the dealer, and Light Gallery, and what we know to be the art world. And now it’s just way out of control.

How do you mean?

Did you see the book I did, Foto Follies: How Photography Lost Its Virginity on the Way to the Bank? All the big money photographers, all the million dollar pictures, Gursky, Sherman, and that crowd, they have to position themselves that they’re not photographers. They’re artists who take photographs. And I find that so insulting to photography. What does that make Robert Frank? Are you kidding? Robert Frank is a genius photographer and he didn’t have a concept when he went across country photographing America. It became a commodity, now their selling prints, they’re selling objects. Cindy Sherman’s a brand. Once you create your brand and your label and your style and your product, you just let the dealers goose up the sales at Sotheby’s. They buy in, they bid up their own photographs to raise the prices.

Cindy Sherman in the late 70s and early 80s was making her “Film Stills,” series which was very similar to what you started out doing, maybe a generation earlier. Her work was received to wide acclaim by the art world, whereas the reaction to your work was one of befuddlement and rejection by the critics. Meyerowitz and Winogrand walked out of your 1968 show at the Underground Gallery; Winogrand said, “This isn’t photography.” Maybe a generation after Sherman, you have another troupe of young artists who are making these kinds of constructed, staged photographs, like Alex Prager and Holly Andres, being well received in the art and now editorial world. So the mode you invented, in a sense, has become quite mainstream. As someone who I interpret as always having a kind of contrarian’s attitude toward dominant trends of the medium, how does this development affect the work you do today?

That’s the cycle. The paradigm of photography in those days—you could be Ansel Adams, you could be Robert Frank, you could be Cartier-Bresson, you could be Irving Penn and Avedon. That was the definition of photography. As I said earlier, you are either defined by the medium or you define the medium. Winogrand was defined by the medium. I redefined it. I was the first person who, rather than photographing a corpse to capture death, rather than photographing in a funeral home or a cemetery—those are the facts—I want to know what happens when you die. I did “Death Comes to the Old Lady.” Critics didn’t know what to write about it. It was conceived of as being flawed because there wasn’t a decisive moment.

That was very liberating, but redefining the medium was not on the agenda. I realized that’s what I was doing later. But at the moment, it was simply the only way I could express. The tradition is this, something starts out being a new idea, contrary to the given of what photography was, and then eventually, that new idea is incorporated into the system into the concept and it becomes… I remember once when somebody told me I was the establishment. I was literally shocked. How could you say that to me?

It was not about the photo establishment it was only ever about being… If I had followed the rules, I would have never written on a photograph. I would have never painted on a photograph. And the rules will keep changing.

You never supported yourself with your personal work, you don’t consider your audience. How do you then deal with the success and recognition you’ve had?

I’m 82, and when you’re 28, the rules are completely different. There’s certain behavior that’s appropriate when you’re 28 and 48, and the rules keep changing, and the rules at 82 are quite different. So I don’t have to prove anything anymore. I’ve already defined who I am with the work, so it’s nice. It’s nice, and my timing is good. If this had happened when I was 60, or whatever, it would have been quite different. Sometimes it’s bad to peak too soon. That would have been peaking too soon. I’m right on schedule in terms of peaking.

The odd part is to realize that I’ve got most of my work behind me. I realize that I’ve got 95% of all I’ll ever do behind me. That’s a strange concept. I’ll continue to work because I always do, and artists tend to live longer—Picasso lived into his 90s—because they’re always working. People say to me—it sounds almost condescending—‘oh are you still working?’ It’s just my natural energy. It’s all about energy and creative people have a lot of it.

“Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals” is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh through Feb. 16, 2014.

Michals’s latest book,_ ABCDuane: A Duane Michals Primer, _was published by The Monacelli Press in November 2014.