Hank Willis Thomas’ Confederate Flag Exhibit and the Disruption of Oppressive Symbolism

A timely transmedia installation at the Chrysler Museum in Virginia

Hank Willis Thomas recalls growing up loving “The Dukes of Hazzard.” “I even had the General Lee,” he tells American Photo, referring to a replica of the Dukes’ car, a classic Dodge Charger emblazoned with the Confederate flag on the roof. “There were other African Americans in the community that I grew up in that had that same car, had played with it with pride, and no irony, and none of their parent’s had anything critical to say about it. I think that speaks to the power of popular culture and it’s ability to translate symbols that can be politically charged into something that seems or feels benign. And I think that’s really fascinating.”

Visual symbols are tricky. On the one hand, as dominant strains of critical theory over the last half century claim, they have no meaning, or none at least beyond the eye of the individual beholder, weaving their own lifetime of experiences into a thoroughly unique interpretation upon each view. Meanings mutate, multiply, or disappear, but some nevertheless persist. When photos of Dylann Roof draped in the rebel flag emerged in the aftermath of his cold-blooded murder of nine parishioners at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina on June 17, 2015, there was no denying what it meant.

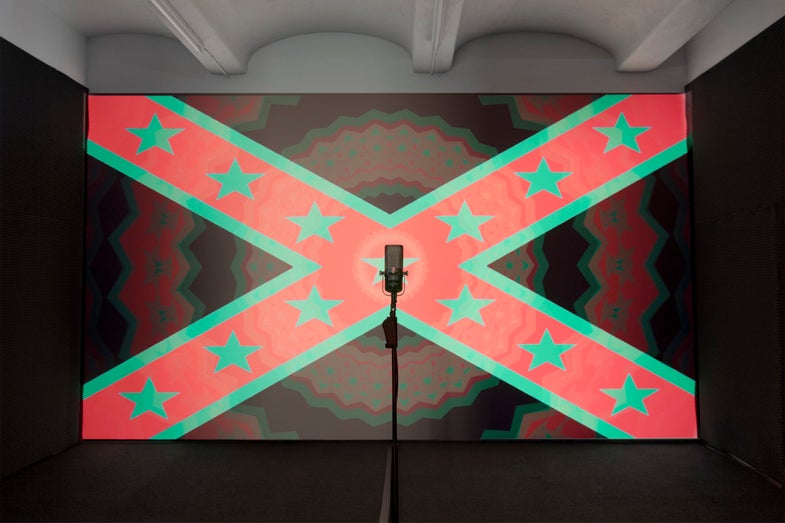

The day after the tragic massacre, coincidentally, Thomas’ latest transmedia installation, organized by the late curator Amy Brandt, was scheduled to open at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, seeking to interrogate that very symbol, and in his words “disrupt” its historical oppressiveness. It consists of a single channel video projecting kaleidoscopic patterns of the Confederate flag, filtered through the hues of the Black Power Movement. The flag is distorted to the beat of a 50-speaker soundtrack, “African American and Afro Caribbean voices of dissent or voices for justice,” Thomas says, from MLK, Malcolm X, and Gill Scott-Heron to Chris Rock and Kanye. “It’s trying to speak to the power of the aural legacy of protest, redefinition, and celebration of the late 20th century,” he adds. In front of the image stands a microphone inviting viewers to contribute to the dialogue and incorporate that legacy into the 21st century during pauses that punctuate the soundtrack.

Concurrent with this installation, our country has undergone a moment of intense national dialog and seemingly rapid shift of cultural values—the flag has quite quickly started coming down from public spaces and retailers’ shelves across the South. “I wouldn’t say it was surprising, I think it’s about time,” Thomas says. “The work that I do is speaking to that need, the need for us to face each other and our history. You can argue that our country is defined by the moments of disruption we’re experiencing now where you can see radical shifts in in relatively small periods of time, but these are struggles that have been decades or centuries in the making and they’re just finally reached their boiling point.”

A part of this zeitgeist, Thomas says, is the shifting role of the artist. This current installation seems like a fairly natural transition from his previous transmedia project, “Question Bridge,” which will be published in book form by Aperture this fall, though a significant transition from the still photographic work of his early career, exploring race and representation often through commercial imagery.

“We could all break outside of our boxes and see ourselves in new ways,” he says. “The lines that once really easily defined and divided mediums, they’re becoming blurry. Photographers are learning how to become video makers and video makers always have seen themselves as extensions of photographers. It’s moment of recognizing the need to cross boarders.”

“In The Box: Hank Willis Thomas’ Black Righteous Space” is on view at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, VA through Oct. 4, 2015.