The First Modern Street Photograph Ever Made

Or, failing to define “street photography”

To proclaim something ‘the first,’ or to fit it under any superlative as makers of internet today are wont to do, inevitably will ruffle some feathers. And in the photo world, few things are as contentious as the limits, definition, and assessment of street photography. On the one hand, the label may be used to elevate an ordinary snapshot taken within the public sphere into something that speaks more about the human condition at large. On the other, it may reduce an otherwise perfectly good ‘documentary’ photograph into something more specifically about a solipsistic pursuit.

For Street Week here at American Photo, we’re showcasing portfolios that push the traditional limits of the genre—images that are posed, made in suburbia, or rely heavily on artificial light. To me it seems that modern street photography doesn’t even necessarily need to be made on the streets to qualify. Notable series shot underground in the subways of New York by photographers Bruce Davidson and Christopher Morris are also kind of exemplary of the genre, suggesting that perhaps it’s more about an aesthetic sensibility, or an eye for thematic grit.

[Related: How Instagram Changed Street Photography]

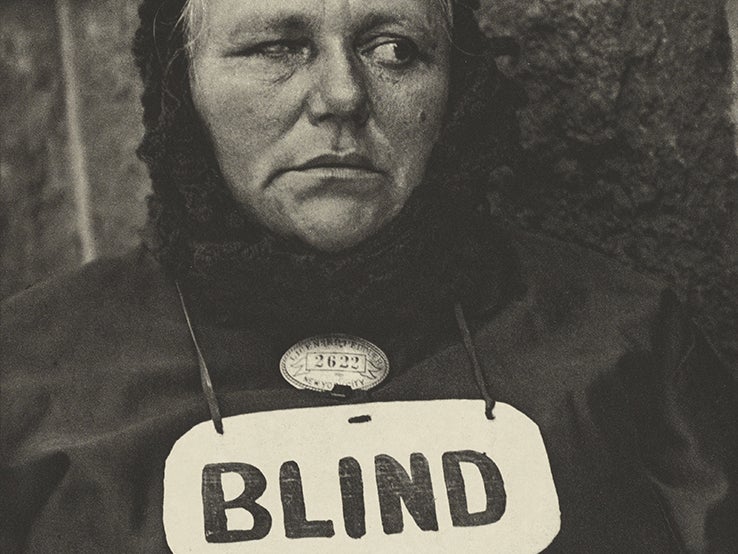

Despite a definition so elusive, we humbly propose Paul Strand’s 1916 photograph titled “Blind,” as a reference point for the origin of street photography. The image was made in New York, a single exposure shot on a view camera, most likely the Adams Idento he used for much of that decade, which made 3¼ x 4¼ glass plate negatives. According to Anthony Montoya, the former Director/Curator of the Paul Strand Archive, Strand fixed a dummy lens to his camera, or what the MET (which now owns the only vintage platinum print of the image ever made) calls, a “prismatic” lens. This allowed him to photograph at a 90 degree angle from where he and his camera were faced and avoid being noticed, making “Blind” one of the earliest noted surreptitious images. Montoya says it’s not his most reproduced—that would be “Wall Street,” 1915—but it is arguably his most important because of how it prefigures his significant contribution to portraiture in years to come.

Surely, one must think, that by 1916, nearly 90 years after the inception of the medium, couldn’t there have been some other street photograph that predates? It seems so obvious and simple of an impulse—after all, the very first photograph ever made, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s “View from the Window at Le Gras,” c. 1826., is of a street, though it wasn’t made on the street. The photographs of Jacob Riis shot throughout New York slums in the 1880s definitely fit the aesthetic or thematic qualifier we mentioned before, but that body of work is much more unified and sustained and prefigures social documentary photography, which most agree stands apart from, though doesn’t necessarily exclude, street work. Then there is the question of Stieglitz and Atget, both of whom predate and are likely the best fracture points to our claim.

The reason we’ve chosen Paul Strand’s image is not because nothing dated earlier could qualify, it’s that his is among the earliest, most significant, and influential photographs that across form, content, and means of production best anticipates the development of street photography as we know it today. Strand’s desire to be invisible on the street and minimize the presence of the mechanical barrier between subject and photographer anticipates the two big points when the genre exploded—first with the development of compact and reliable take-me-anywhere 35mm cameras, and exponentially after with the advent of the utterly inconspicuous camera phone. The image challenges the idea that photography had to focus on conventional ideals of what’s beautiful, it is socially engaged with issue of poverty, but it is equally concerned with the forms, lines, and clean tonal fields of modernism. The interplay of visual and textual data within the frame, in a particularly self-referential way, anticipates similar juxtapositions, ironic or otherwise, that street photographers commonly use to this very day (note this image by Ruddy Roye made nearly a century after).

Finally, it seems pertinent to anoint an American photographer above others, not from a jingoistic impulse or to fulfill any supposed mandate from our publication title, but because, quite frankly, the genre is weaved into our very culture as one of the earliest modern open societies. Many, though not all, significant bodies of work in street photography—Frank, Winogrand, Levitt, Friedlander, Maier, Meyerowitz—were made in America because our culture has allowed it to cultivate and flourish. It would be foolish to discount the contributions of someone like Cartier-Bresson, but French culture is markedly different in that the nation has all but outlawed street photography for privacy concerns come this day and age. In contrast, over the last century, US courts have repeatedly ruled—in cases involving Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Arne Svenson, and others—that any reasonably expectation of privacy on the street, in the public sphere, may be violated not only for news gathering purposes, but for this very type of creative expression. Though it is controversial at times, street photography, as defined by the image above, has challenged us and brought new ideas into consciousness. If its point of conception, a century ago, is less than certain, what we can be sure of is the continued debate and excitement it will generate in the century to come.