Danny Lyon: Coal Comfort

The following is excerpted from Danny Lyon’s new limited-edition book, Deep Sea Diver (Phaidon Press, $200, phaidon.com). Over the course...

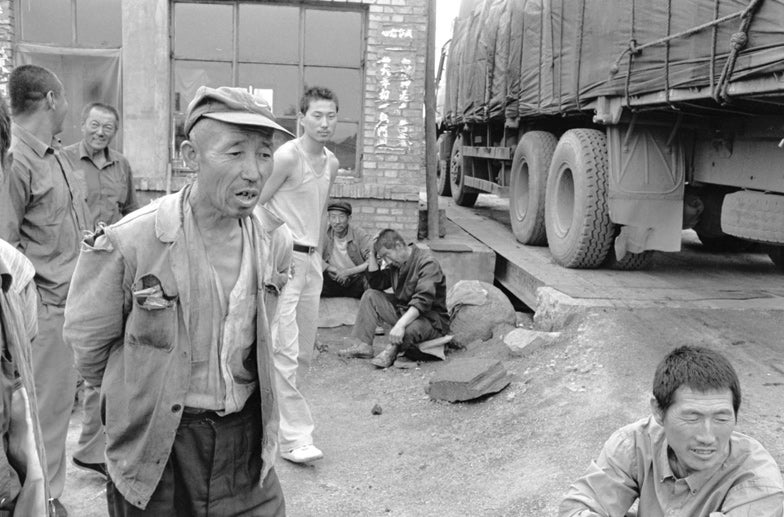

The following is excerpted from Danny Lyon’s new limited-edition book, Deep Sea Diver (Phaidon Press, $200, phaidon.com). Over the course of four years, Lyon made six trips across northeast China to document Shanxi province, as he describes it, the “Appalachia of China.” Shanxi’s largest industry is coal mining. Lyon was determined to photograph it, despite run-ins with various local and national authorities. In this particular encounter, his translator was a young man named Weifeng. Danny Lyon maintains a blog and website at bleakbeauty.com. Go to them.

From the beginning of my China work I had wanted to get into a coal mine. In addition to the large legal mines in Shanxi, there were hundreds of small illegal ones, all bringing up the valuable black rock, anthracite, that powered much of China. These mines could be as small as a hole in the ground and, because they were so dangerous, the government in Beijing has been trying to close them. The government has admitted that almost 6,000 miners died in accidents in 2005, most of them in illegal mines, many in Shanxi. I had often driven to illegal mines, but they were always shut down.

On an earlier trip, I had driven right into the huge Datong Mine and walked into the building unnanounced. It took about five minutes for someone to notice me and ask me to leave. This time we pulled up beneath the Wu Guantun Mine, which had high, pink-painted walls all around it. A dozen empty trucks were lined up on the hill, waiting to get inside. I began by making pictures of the truck drivers—and, by doing so, slowly worked my way up the slope toward the entrance to the mine. Everything was covered in coal; the roadbed itself was made of small pieces of compacted coal.

At the very top of the slope was a crumbling concrete staircase heading up to the tier above us and beyond where the large buildings above the mine stood. I began to slowly ascend the stairs with Weifeng behind. At the top of the stairs, a single person in a camouflage uniform was sleeping against a building, clutching a cellphone. He seemed benign enough, so I slowly turned around and looked straight at the mine. And there they were, about 50 yards away, the men I had come for—right on schedule, helmets still on their heads, coal dust all over their uniforms, marching in a group of about 10, with a few stragglers. I knew what I was looking at. It was 8 a.m. The night shift was leaving the mine.

Since I had tried this once before and failed, I knew what lay ahead. With a single Leica on my arm, I told Weifeng to hide my M4. I stepped over a knee-high fence and walked across the lawn and onto a path that led toward the miners, who had entered a building 50 yards away. It took just a minute to reach the building and step inside. Down the corridor I could see a single miner in his helmet and filthy army-green suit standing against the wall. I walked directly toward him. It was important to keep moving forward. No matter what the circumstances, just keep moving; whatever the obstacle, step around it, keep moving; if someone engages you in conversation, either ignore him or carry on the conversation as you walk, maintaining your forward motion. I walked rapidly into the hallway in which the miner stood and, turning right, I saw a group of men jammed up in the hallway about a hundred feet ahead of me. I walked directly toward them. I passed a large caged area with wooden shelving filled with cubbyholes, each one either empty or containing a miner’s light. As I marched past the miners, one was leaning into the cage, giving his lamp to a woman inside who was making a notation in a logbook. I kept moving past them up the hall, toward the staircase ahead.

Testing Title

The stairs led to another corridor, which led to a door; I walked through it and into the locker room. A partly dressed miner stared at me as I passed. Another one, across the room at his locker, looked up. Ahead was a large room. I walked through it. Then, turning to the right, I could see before me, across a hallway, the showers and the baths—all filled with miners. Bright daylight poured down from the windows and skylights.

In my left hand was my M6, with its 35mm lens and an internal light meter. I wanted to use the M4, which has a shorter lens, but that meant taking a light reading with my Sekonic meter, which was on my belt. It also meant turning to Weifeng to ask for it. That would take seven or eight seconds—an eternity for a photographer standing in the showers of a Chinese coal mine. I lifted the M6, set the exposure to half a stop under, and made the first picture. Just in case it was to be my last. Then I stepped inside the shower room. One of the men in the locker room had started to move toward Weifeng, and I assumed that the two were talking not far behind me.

Ten feet into the room I was standing directly over a large wading pool. It was filled with men. My foreground. In the background was a second, smaller pool, also filled with men. A few men were standing along the side, taking showers. I was in the perfect spot to make the picture I had come for, so I made it twice, or more. The entire scene filled the frame.

I began to walk around the side of the pool. By now the men were looking at me with amusement so I waved at them, causing one or two to wave back and others to laugh. Now, facing the showers, I made another picture, but in the nanosecond I had to study it, I thought it was not as good as the original pictures, which had taken in the entire room. So I turned to the smaller pool right below me, where the men were now smiling and looking directly up at me. Then, standing at the edge of the pool, I had to make a decision. One part of me felt that I had succeeded in entering the baths with my camera, and that I might be in a friendly environment, in which case I should go back into the locker room and make portraits of the men undressing, perhaps find more men coming in with their lanterns and dirty clothes and faces and photograph them. The other part of me argued that eventually someone would use a cellphone to call security to tell them that a foreigner with a camera was inside the building. If we were confronted here in the shower we were trapped, and the chances were excellent that we would lose the pictures I had just made, and also any other exposed film that was inside the second camera or might be stuffed inside my pants pocket. The whole thing happened so quickly that I hadn’t bothered to take the simple precaution of emptying my pockets of exposed film or starting with fresh rolls in both cameras.

I waved to the miners again, turned, and walked out of the shower, Weifeng following me. First back through the locker, then down the stairs, past the lantern room, down another flight of stairs, and then, at the first exit we saw, out into the daylight—this time, on the other side of the building. We stepped out onto a rosebush-lined walkway inside the miners’ village. Below us on the main street were women, each with their single child, and well-dressed miners walking with their wives and children, a regular Sunday scene. We stepped down into the street and joined the families. I turned to Weifeng, who was walking next to me.

“We did it,” I said. AP