25 Years of American Photo: The Gear Story

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more › For...

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

For our 25th anniversary issue, we asked photo experts to weigh in on the most important trends of the past quarter century, a time of incredible transformation in photography.

Like the universe it inhabits, the development of photographic technology is accelerating at an exponential rate. Consider that when the first issue of American Photo appeared in January 1990, the big bang of digital capture was still a couple of years off. Working with images on a computer was an exotic idea, hampered by primitive software; filmless photography meant video stills saved on a downsized floppy disk.

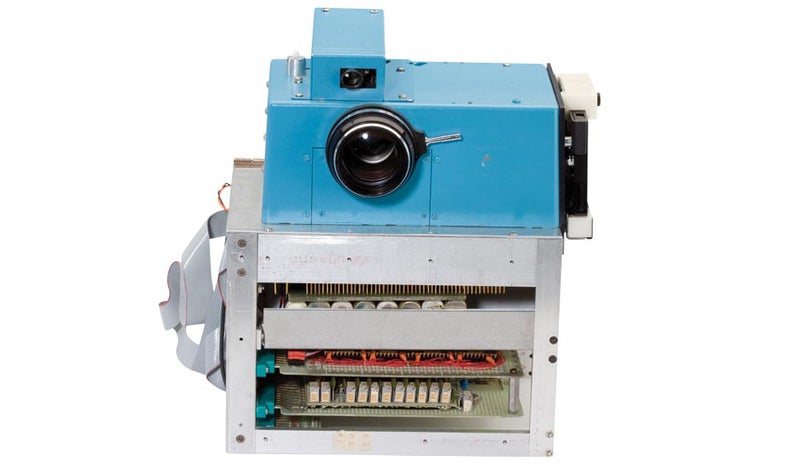

Yet even before the realization of digital capture, technology was helping to blur the lines between the once-discreet precincts of art, editorial, and advertising photography. In the early ’90s, professional photographers began to adopt ideas and techniques from other genres and borrow from consumer technology, just as pros today shoot with iPhones. Then technology threw a $20,000 wrench into the photo world. In 1992’s January/February issue came word of the Kodak Professional Digital Camera System, the first true digital SLR. It was a manual-focus Nikon F3 fitted with a 1.3-megapixel image sensor and tethered to a massive shoulder pack for image storage and review. Digital capture had arrived, albeit still out of reach for most photographers.

The price of digital cameras would soon go into years of free fall, bringing them into the realm of newsgathering organizations and then of amateurs within a decade. In the November/December 1999 issue of American Photo we ran a story about how photographer Chip Simons was submitting his assignments—by modem—shot in maximum JPEG with the Nikon Coolpix 950 compact. Just one year later, though, came the 3.25MP Canon EOS D30, at $3,000 the cheapest DSLR yet. That epochal camera gave many photographers a new comfort with digital capture. This magazine might claim it was prescient in offering a mid-2003 page of new cell phones with built-in cameras, but no one could have known the extent to which Apple’s iPhone, announced in 2007, would come to dominate photography.

Then things seemed to change, both in the pages of American Photo and in photographic culture at large. The emphasis shifted from camera technology to how to manage the exponentially larger number of images that it allowed photographers to create. Workflow became the buzzword as we ran more and more stories about the ways in which digital was changing photographers’ working lives, mostly for the better. We taught everything from how to read a histogram to how to make good prints—something photographers had not been able to do on their own since abandoning their wet darkrooms.

Yet many new products helped regraft the medium to its roots, whether upscaling DSLR image sensors to the physical dimensions of the once-familiar 35mm frame (the Canon EOS-1Ds); ramping up DSLR resolution to a level once achieved only with medium format (the Nikon D3); or even successfully bringing the classic rangefinder into the digital age (the Leica M8). There were a few fond farewells, though. In 2011 American Photo told the sad tale of how National Geographic’s Steve McCurry went about shooting the very last roll of Kodachrome. And now progress seems to have come full circle, as some of today’s most cutting-edge photographers, who were reared on digital, make their best work by taking up film as their medium of choice.

Russell Hart is former Senior and Executive Editor of American Photo magazine (1990–2011)