Ruth Gruber: Witness for the World

I first picked up a camera as a student. When I looked through that Leica for the first time, it...

I first picked up a camera as a student. When I looked through that Leica for the first time, it was wonderful. Later I got a Rollei. I was so startled when I looked in it. You could see a whole scene there. I didn’t think a camera could do that. People ask, “Did you take a course?” Who took courses? You just learned by doing. The camera taught me.

At 18, I got a fellowship to the University of Wisconsin to study German and English literature. From there, in 1931 I got a fellowship to Cologne, Germany [where, at age 20, Gruber became the world’s youngest Ph.D.–Ed.]. After I came back to New York, I used to go to Romany Marie’s restaurant in Greenwich Village to have coffee. She had certain tables for very famous people. One was for Vilhjálmur Stefánsson, the famous Arctic explorer. One night I was at the restaurant with Edna, my best friend from junior high, and Romany Marie mentioned to Stef (as we all called him) that I had just come back from Germany. He had a lot of reports from German ship captains and he hired me to translate them. I’d go to his place whenever my classes were over and work for him.

In 1935 I traveled through Europe and the Soviet Union on an exchange fellowship from the Institute of International Education. Stef gave me a beautiful letter of introduction to a famous geographer, who I met in Leningrad. He introduced me to Otto Yulyevich Schmidt, the Czar of the Arctic. Schmidt asked me if I’d like to go to the Soviet arctic. I knew that nobody had been allowed to do that before. I tried to be casual. I said, “Well, I think I might like to go.” I hoped he wouldn’t see how my legs were shaking. He said, “Whenever you’re ready, we’ll send you.” I went back to Moscow, and I told some of the famous reporters that I was going to the Arctic. I think if they had a knife, they would have cut my throat.

I had done some writing for the New York Herald Tribune and when they heard that I was going, they said, “Whenever you see a good story, send it to us.” There was so much to photograph, so much to write. The more I wrote, the better the pictures were. The more I took images, the better the writing was. The two interlock so beautifully.

After I came back, the Herald Tribune sent me to interview Harold Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior under Franklin D. Roosevelt. When I met him we talked about my time in the Arctic. He ended up hiring me to go to Alaska to do a study for him. The indigenous people loved the magazines I brought, especially Life and Look. They loved those photos. The ship with food, clothes and magazines only came once or twice a year up there.

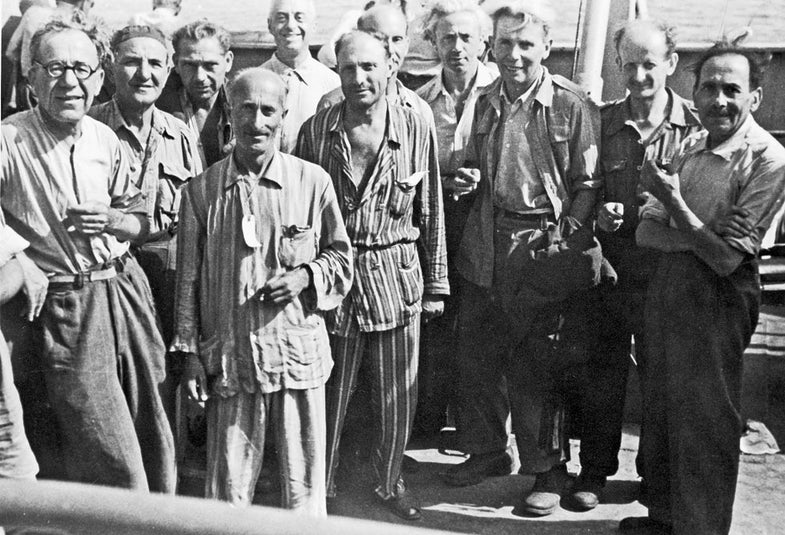

After 18 months in Alaska, Ickes hired me as his special assistant. I wrote letters for him. In 1944, after parts of Italy were liberated, there were people in European internment camps who wanted to come to the U.S., but the U.S. had rigid immigration quotas in place. Roosevelt got around it by secretly making 1,000 of them guests of the president. That allowed them to be brought into the U.S. during the war. It was a mix of concentration camp victims and others who’d been hidden from the Nazis during the war, some in monasteries, others in people’s basements. They were brought over on a boat called the Henry Gibbins. Ickes asked me to go to Italy and ride back with the refugees to take their case histories and help them acclimate.

In 1946, after the war ended, and before the formation of Israel, there were a lot of Jews in the European displaced person (DP) camps that wanted to go to Palestine, which at that time was controlled by the British. President Truman asked the British to let the Jews in. Ernest Bevin, the British Foreign Secretary, was against it, but couldn’t say no to Truman after the way the U.S. had helped the U.K. during the war. So he made a deal. They formed the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine. Six Britons and six Americans would travel for four months through the DP camps and the Arab world to evaluate whether 100,000 Jews from the camps would be allowed into Palestine. Bevin said that if the committee voted unanimously for it, they would let the refugees in. He figured it would never happen.

I was still working for Ickes when I got a call from the editor of the New York Post. He said, “Ruth, we need you. Take a leave of absence from your job and travel with that committee.” I said I’d have to check with my boss. Ickes said, “As long as I work here, I need you.” So I called the newspaper back. “The boss says no.” But the next day Ickes called me to his office and said, “I was wrong. You must go. You owe it to your people. Just write me a resignation letter first.” He knew he’d quit soon. He and Truman were fighting all the time, mostly about oil. Ickes felt nobody should be allowed to drill for oil offshore, because he foresaw the damage it could do. And look what happened.

So I joined up with the committee. We went to the DP camps in Germany and Arab villages in Palestine. Then the committee voted. They were unanimous. The Jews would be allowed into Palestine. Three days of joy. They were dancing in the streets in Tel Aviv and New York. They were going to get 100,000 DPs into Palestine. Everybody was so thrilled. Then after three days it was dead. Bevin and the British government rejected the recommendation. I returned to the States.

The following year, the Herald Tribune sent me to Palestine to cover the arrival of the Exodus 1947. Activists had arranged for the ship to carry 4,500 refugees to Palestine from the DP camps in Europe. When they tried to enter Haifa Harbor, the British rammed the ship from two sides. You can see the destruction in some of the pictures I took. The Jewish leaders in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem had sent word: “You can throw fruit, you can throw meat, but you cannot shoot. We are not killers.” So they had no weapons. The British came onto the boat with sticks, with guns. They killed one of the mates, Bill Bernstein, because he stood in front of the wheelhouse to prevent them from taking over the ship. A 16-year-old orphan was looking through a porthole and saw one of the marines coming up with a gun. He threw an orange at the marine. The marine shot and killed him. In the struggle, another 16-year-old was killed and more than 100 were wounded.

They brought the ship into the harbor and made them throw all their belongings, which were just rags and stuff, in a pile. They said, “Don’t worry, you’ll get them back.” Of course they never saw them again. You could see women looking for children. You could see them searching for their relatives. They were taken to a temporary prison camp in Cyprus, and after that they were loaded onto three prison ships, the Ocean Vigour, the Empire Rival and the Runnymede Park. Then the British deported them back to France.

So I went to France. When they arrived, the refugees refused to leave the ships. I knew I had to get aboard one of them. The British Consul was only going to allow three journalists in, one from England, one from France and one from the U.S. I was selected to represent the Americans. It was sheer luck. And I was the only one with a camera.

I was let on to the Runnymede Park, which had 1,500 of the refugees from the Exodus. When I went aboard, they said, “You’re on your own.” When the refugees learned that they had an American Jew on board, they raised a banner. They had painted the swastika on top of the Union Jack. I took endless photos of it. They became the most famous pictures I ever took.

These were Jews the world had never seen before. They were going to live. They showed me what it means to fight. Not politically or non-politically, but to fight to survive. I talked to them for a while. They said, “Go below. Go see our floating Auschwitz.”

So I went below, and there they were: over a thousand people in the hold of the Runnymede Park (see gallery above). They were only allowed to come up from the bottom for two hours a day. That was when they could use the outhouse—six holes for 1,500 people. The rest of the time they were locked up in this cave. There were babies everywhere. The men and women were determined to have babies. It gave them back their being.

When they found out I was a Jew from Brooklyn, they said, “Would you tell our families we’re alive?” And they wrote telephone numbers down. I promised to call all their relatives. Some of them had families that hadn’t heard from them in years.

Witness

When they saw I had a camera, they said, “Take pictures. Let the world see how we’re being treated here in this horror.”

So I took pictures. There was a woman with a baby—a gorgeous, gorgeous baby. And I said, “Your baby is so beautiful.” She said, “I know. But I’m finished. I can’t live anymore.” I said, “Don’t talk that way. You’ll get there.” She looked at me, and I looked at that baby. I said, “Can I hold it?” She said, “Yes.” So I cuddled it. At that point I didn’t know who needed the hugging more, that beautiful baby or me. I asked the woman, “How old are you?” She said, “Twenty-three.” I said, “You’ll get there. Don’t worry. They can’t do anything more to you.” And she said, “I’ll live, because I want the world to know what we’ve gone through.”

After we got off the ships, the British Consul called us all together. That’s when he noticed I had my camera. He yelled at me in front of all of the reporters, “You took pictures! I demand your camera and the photos!” I said, “I’m sorry, sir.” And I turned on my heels and I walked away.

When I got back to the hotel I had the film printed immediately. Then I called the head of the Paris Herald Tribune and told him the story. He said, “Who has the pictures?” I said, “What do you mean who has the pictures? I have the pictures!” He said, “Well, write your story. I promise you we’ll run it first page. Then come and see me.” So I wrote the story and took the pictures to him. He looked at them and said, “Ruth, I get photos every day, and I never cry.” He said, “I looked at your photos, and I cried. They don’t belong to you. They don’t belong to the Herald Tribune. They belong to the world.” And that’s the way I looked at them after that.