Photos From the Final Frontier

When NASA’s Curiosity rover landed on Mars on Sunday night, the first thing it did was send back photos to...

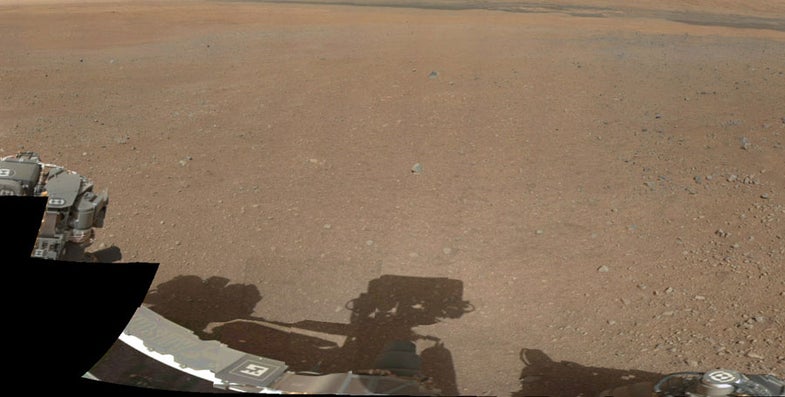

When NASA’s Curiosity rover landed on Mars on Sunday night, the first thing it did was send back photos to prove it existed, intact, on the surface of another planet 150 million miles away. In fact, the cry in the mission control room of “WE’VE GOT THUMBNAILS!” elicited the biggest round of cheers, both in the mission control room and on Twitter, where hundreds of thousands followed along with the mission’s live stream.

And for good reason. To see those first low-resolution black-and-white images beamed back in real time (after traveling at the speed of light for 14 minutes) is a rare thrill for we Earthlings. With practically every inch of our own planet subject to constant, web-connected photographic documentation, whether it be via smartphone or satellite, it’s interesting to experience images coming from a true photographic frontier—an experience we now have to travel to another planet to find.

Today I came across two interesting posts that frame the Mars landing in terms of its photography. The first is by Wayne Bremser, who connects the first Curiosity photos with an essay written by the famed New Topographics photographer Robert Adams on 19th-century frontier landscapes, and how photographic depictions of them differed from more traditional paintings. Bremser writes:

The main difference Adams points out is, when the painters were confronted with negative space, they filled it with imagination and fiction. Fluffy cotton puffs were dabbed into bleak, cloudless skies. The Colorado Rockies were painted to look more like the Swiss Alps. Photographers were unable to do this. Adams has a great line: “The limits of the machine saved them.”

On Mars, even though it has a cute anthropomorphic face, Curiosity’s photographic ambitions are above all scientific. Paired with the obvious (but no less absolute) desolation of the Martian surroundings, these photos represent a unique view of the landscape.

Writing on Art Info’s Modern Art Notes blog, Tyler Green also draws a 19th-century comparison. What caught Green’s eye is the often inevitable presence of the photographer in the images themselves, whether it’s the wheel of a rover embedded on Martian terra firma or the shadow of a photographer and his wet-plate camera on a tripod. While Curiosity’s foot may not be as ominous as the cheerful hat wave of Timothy O’Sullivan in his image of Shoshone Indians, who would soon be swept off their homelands by O’Sullivan’s white counterparts, it does provide an interesting link to a common practice in early photography.

Timothy O’Sullivan, Captain Buck and Shoshone Indians, East Humboldt Mountains, Nevada, 1868.

Green goes on to show several more early landscapes which featured the shadow of the photographer, intentionally or otherwise, including some work by the great Carleton Watkins. He writes:

The similarity of the pictures from then and now reminded me that the frontier is the frontier, whether it’s the American West in the 19th-century, or Mars in the 21st.

You can watch the latest corpus of true frontier photography beamed live into your living room on the JPL’s Curiosity Multimedia page. Just think of Curiosity as the latest in a long history of photographic explorers, human or otherwise.