Jamaica’s Golden Age of Music, Captured on Film

Sometimes, photographs are produced out of a genuine interest, if not love for a subject; that’s true of the photos...

Sometimes, photographs are produced out of a genuine interest, if not love for a subject; that’s true of the photos that Dave Hendley took of the late 1970s Jamaican music scene, a time and place that, to both his ears and ours, produced some of the best popular music ever. (If you need any convincing about the merits of Jamaican music, check out these two podcasts that Hendley recently recorded in Japan.) Hendley spent time with, and photographed, some of the biggest names of the era, including legendary producers Lee “Scratch” Perry and King Tubby. Yet for all of this exclusive access, it wasn’t as if he was particularly well-connected when he traveled to Jamaica. As Hendley explains it, he knew how to take photographs at the time, having worked a series of jobs in London. Still, he wasn’t going over to shoot a “project”: he was, and still is, a die-hard reggae fan, and he was going to meet his musical heroes in person. It so happened that, at the time, the artists themselves were receptive to foreign visitors.

Hendley has supplied us with plenty of photos for this post, but they almost didn’t see the light of day. He said: “I put such little value on them. In the early 1980s, when some people making a documentary wanted them, I couldn’t be bothered to do prints, so I told them to just take the negative file. I never saw it again for 18 years.” It was only through a chance encounter that he got them back. I talked with Hendley on a recent trip to Tokyo (before he headed off to Osaka to DJ a reggae party) and he told me a few stories about his time with some of the greats of the era—picking out a song for each one.

What got you interested in reggae in the first place?

Back in the late 60s, there was what I guess you coud call a youth cult, skinheads. It was just a kind of look: it was all those ivy league clothes, nice brogues, button down oxford shirts, that sort of thing. There was an element of aggression that went with that too, it was a reaction to the hippie counterculture, which seemed a little bit sewn-up and exclusive to a mass of ordinary people. I see why that kind of negative to the positive came about. Reggae was the soundtrack to that, because the skinheads were choosing the music that would be the antithesis of that complex, progressive rock at the time, that kind of over–intellectualized, over-complicated msuic. What could be more fundamental than reggae? Its beauty is in the space, really, its minimalism, and what’s not there. It was quite attractive.

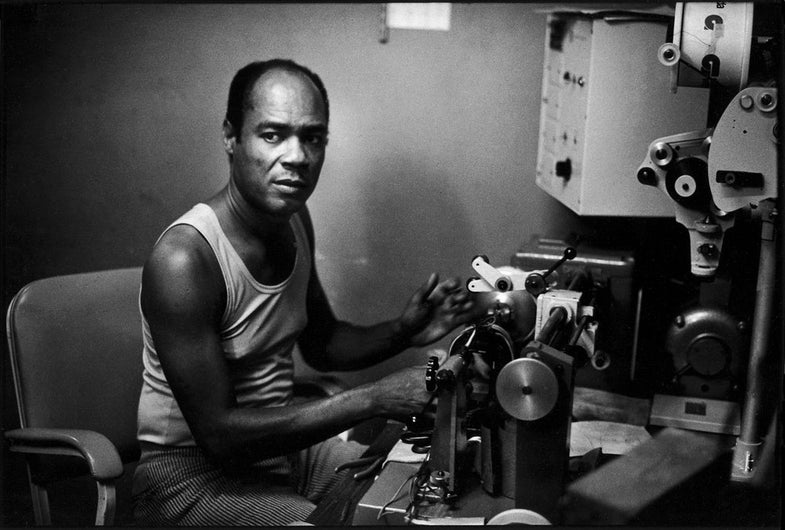

King Tubby

King Tubby, 1977

King Tubby/Augustus Pablo, “King Tubby Meets The Rockers Uptown” (1975) – “Game, set and match the best dub side ever!”

“This wasn’t conceived as a photographic project. The function of the photos was simply to show people back in the UK what these people looked like. King Tubby turned out to be a very serious jazz fan, who didn’t seem to be particularly comfortable with the whole reggae thing. To my bitter regret, I never photographed Tubby more than the three frames I took of him. That’s partly because he was a quite shy person, and it seemed to be inappropriate—he wasn’t comfortable with the idea that he was famous, even in a very limited genre. It didn’t even seem realistic, given the environment and the world that he lived in, which was basically a kind of home studio, or bedroom in his mom’s old bungalow, in the middle of the roughest part of Kingston. The whole idea of him being some sort of celebrity didn’t seem to make sense—it seemed ridiculous—so why would I want to photograph him again and again? It would make me look like an idiot, or that’s how I felt. So I always was very conscious of putting the camera away. I knew about photography, I knew how to use a camera, but I didn’t think that I was a photographer when I took those pictures. There’s a kind of purity of purpose. I never gave any thought to composition, they were just photographs of record.”

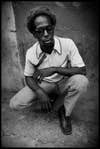

Gregory Isaacs

Gregory Isaacs, 1977

Gregory Isaacs, “One One Cocoa Fill Basket” (1972) – “Solid early 70s rhythm and one of Gregory’s most plaintive vocals. I loved this record for the best part of 40 years.”

“Probably the most pictures I ever took of anyone, in one of those brief encounters where you take pictures for three or four minutes, was Gregory Isaacs. It took me a month to pluck up the courage to photograph him. He had a bad reputation—he was a very sweet singer, but he was also an out-and-out hoodlum. I think it was a Saturday morning, and we were flying out that night, and I thought, ‘I’ve got to get a picture of Gregory Isaacs.’ He was my favorite singer at the time. I saw him down on the North Parade, I said “Gregory, can I take your picture.” He just dropped into a crouched position, he was wearing these very heavy shades, and he just looked completely menacing. I did eight frames, four frames with the glasses off, four with the glasses on—quite nervous, hands shaking.”

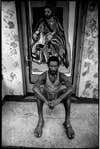

Lee “Scratch” Perry

Lee Perry

The Silvertones (Produced by Lee Perry) – “Rejoice Jah Jah Children/Rejoice Skank” (1973) – “Innovative and mystical roots music that is free from the indulgent overproduction that so often mars The Upsetter’s late 70s output.”

“I was there at that time when he flipped. We’d been there two years previously, when the studio was completely buzzing, people were coming by. Two years later, when I went back, everything changed. His studio was in back of his house, it was fairly residential—it wasn’t the ghetto at all—but you’d be at the gate calling for him, and he was hiding in a bush. It was quite odd. And he’d taken to always having a piece of wood in one hand and a piece of stone in the other, I don’t know why. If you were having a conversation with him, there would be a third person involved in the conversation. He’d refer to this other person, whose name was Pipecock Jackson. If you asked him something, then he would ask Pipecock Jackson, who obviously didn’t exist. It was quite a bizarre experience. I drove all around Kingston with Scratch in the car in that state. It really wasn’t good—I just didn’t know what he was gonna do next.”