At the Intersection of War and Fashion, a Compelling Controversy

Last week, CNN.com published a feature entitled “War & Fashion,” which examines the work of four Magnum photographers. As you...

Last week, CNN.com published a feature entitled “War & Fashion,” which examines the work of four Magnum photographers. As you could expect from looking at the title, the idea was to draw a connection between war photography and fashion photography. And as you also might expect, the feature generated a rash of harsh comments from users across the web (there are already over 750 comments on the article alone), as well as reactions from people outside the photography world: it was mentioned in media roundup columns in the Financial Times (requires registration) and the Daily Beast.

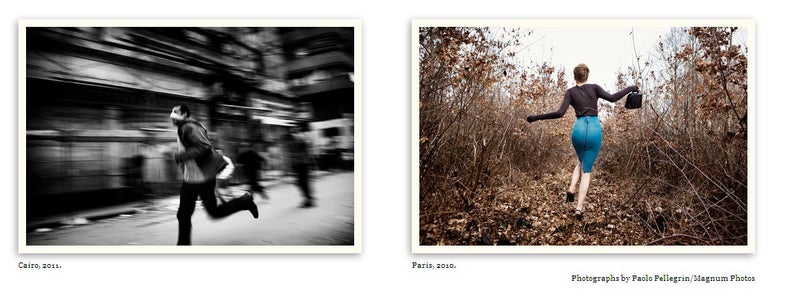

To me, the problem with this article is that it presents a simplistic way of comparing these two genres of photography, and then throws the ball to other people to provide gut-reaction quotes about the idea. The article states: “At first, photographing war and fashion appear as incongruous acts that are difficult to reconcile. Until, perhaps, you take a deeper look.” That’s as much analysis as we get. After that, the point is made in a superficial way, by juxtaposing images of war and fashion that share a similar composition. Of course the article is not saying that “fashion and war are equivalent,” but rather that “fashion photos and war photos sometimes look the same when they’re taken by the same person.” This statement isn’t controversial at all, though—isn’t that obvious? It’s safe to say that most photographers have a consistent way of working, which means that there should be some consistency between photographs they take of different subjects.

A spread shown in CNN’s “War & Fashion”

But what is controversial, or inflammatory, is the choice to base what is a simple observation about similar aesthetics on the genres war and fashion, when it would have made just as much sense to compare war and sports, or sports and fashion, or fashion and landscapes, or landscapes and portraits. This list could continue without end, because it’s just not that difficult to find superficial similiarities between different kinds of photographs, especially when they’re taken by the same person (most news agency photographers cover a wide breadth of events over the course of their careers).

What’s most disappointing is that this provocative feature represents a missed opportunity to say something meaningful or interesting about this juxtaposition. A true cynic might wonder if they did it simply to drive traffic and buzz, but in any case it’s not difficult to sympathize with the reaction of Sonya Fry, executive director of the Overseas Press Club, who is quoted in the article as calling the comparison “appaling.” That’s the only word she’s given, and I’d be curious to hear the rest of what she said.

Because the question the article was trying to pose, if we give it the benefit of the doubt, could not be more interesting: why and how do war photographers (even going back to the legendary Robert Capa himself) shoot fashion? Is it because fashion work pays more than photojournalism? Because the skillset of shooting under fire lends itself to a particularly unique view of fashion? Or is there some other connection between the two worlds? In many cases, I would assume it’s a result of photojournalists simply moving from assignment to assignment; sometimes the nature of the business creates these unexpected juxtapositions all by itself.

When we spoke with Getty photographer Ben Lowy in late 2011 on the occasion of the publication of his award-winning book Iraq | Perspectives, he recounted an especially extreme transition from war to not-war, via 2008’s New York Fashion Week.

I had just survived a suicide bombing in 2008. I was still in Iraq when the photo editor for New York magazine, Jodi Quon, called to give me that fashion assignment. She called me on my New York phone. It was afternoon in Iraq and I was driving back from the hospital where I was visiting my friend who was injured in the bombing. I remember being like “yeah, I’ll do it.” I’d take whatever work came my way, but it was very unexpected. I didn’t know how to deal with it. I was still wearing pants that were bloodstained.

So, I left Iraq and went to Easter Island for another assignment. It’s a 36-hour flight. Then from Easter Island I went back to New York and right away started shooting this fashion stuff. The first show that I got to — I don’t remember the designers name, but she was having a complete meltdown. None of the pieces looked good and the models were making fun of her and something wasn’t dressed right and the makeup was wrong. It was the worst day of her life. I just thought, “I just survived a suicide bombing and there were body parts all over the street and you fucking suck.” I remember thinking, “how can I do justice to this while still giving respect to what I had just seen?” I struggled with that for a long time.

Lowy goes on to explain how what was initially disgust for a world he had little respect for changed his photographic approach. “I just wanted to make it grotesque in a way,” he says, recounting his use of harsh ground-up strobes to cast dark shadows on the faces of the models and designers he photographed. But eventually, that disgust was tempered by acknowledging that the fashion world is real, too–while being about as different as humanly possible from a war zone. Despite interviews with some extremely well-respected photographers, the CNN piece doesn’t explore any of these questions in depth.

In all of this, it’s worth keeping in mind that the feature was created with the cooperation of Magnum, the legendary photojournalism agency. (Blogger John Edwin Mason wrote about his reaction to Magnum’s involvement.) As a field, photojournalism is being threatened by the presence of amateur photographers, but one area that seems safe from civillian intrusion—maybe the last stronghold of photojournalists?—is war photography. Going back to interviews with snapshot extraordinnaire Michael Jang, the key thing is access, and war photographers certainly have that. I’m not sure why Magnum would go along with such a shallow feature when it seems like they’re devaluing what might be one of their last truly valuable assets.